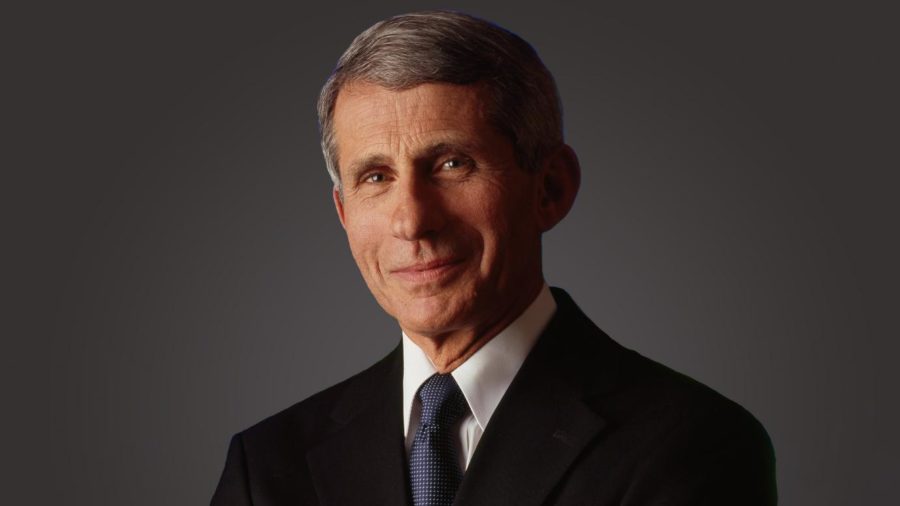

Anthony Fauci received the 2020 Harris Dean’s Award at a virtual ceremony on Thursday, March 4, for his contributions to public health policy during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The longtime director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) within the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Fauci succeeds the late Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg in receiving the award, which is “bestowed upon an exceptional leader for his or her lifetime contributions to public policy.”

Fauci has long been a prominent figure in American public health. He joined NIH as a clinical associate in 1968 and progressed through the agency’s ranks to become director of NIAID in 1984, during the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Fauci served on former president Donald Trump’s White House Coronavirus Task Force in 2020 before being named chief medical adviser to President Joe Biden in January.

In response to questions posed by Katherine Baicker, the dean and Emmett Dedmon Professor at the Harris School of Public Policy, Fauci called the COVID-19 pandemic “a very painful learning experience.”

“[COVID-19 is] unlike any virus that I’ve had any experience with,” he said. “[When] have you seen a virus in which almost half the people get no symptoms, and yet it can kill a half a million Americans thus far and a couple of million plus globally? That’s just not the way respiratory viruses have worked historically.”

According to Fauci, changing information about the virus made it difficult to keep the public properly informed.

“You’ve got to go with the data that you have. And if that means changing something that you said, you should not feel badly or even guilty about having to do that, as long as the science drives what you say,” he said.

When Baicker asked where better data could have been collected, Fauci pointed to testing as an area for improvement. Frequent and widespread testing, he explained, would have allowed federal and state governments to respond more aptly to the pandemic, particularly given the long incubation period of the virus. “By the time someone gets sick, it represents the tip of the iceberg of who’s really infected,” he said.

In the United States, the pandemic coincided with the 2020 election cycle and a summer of political upheaval, posing an additional challenge for epidemiologists, according to Fauci. “We were fighting an epidemic in the middle of one of the most divisive periods in…recent memory,” he said. “You have public health measures that are assuming a political [nature].”

Fauci said that the decentralized federal system, which cedes authority to individual state governments, made a nationwide pandemic response more difficult. “The virus doesn’t know very much the difference between Louisiana and Mississippi or between New York and New Jersey or between Idaho and Montana, [so] you’ve got to do some things that are really uniform. And that was one of the things that actually was the weakness in our response.”

Fauci and his team also had to grapple with health disparities among racial and age groups. A majority of those who died were at least 75 years old, while Black and Hispanic populations in the U.S. also faced disproportionately high death rates.

Communicating these disparities to the public proved challenging, according to Fauci. “How do you get people to care about not being part of the propagation of an outbreak that almost certainly will not affect them in a serious way but has a devastating impact on morbidity and mortality of other people?”

Ultimately, though, Fauci believes that the fate of the pandemic rests in countries’ willingness to defeat a virus he termed “the common enemy.”

“A global pandemic requires a global response,” he said. “There are parts of the world [where] we could have variants coming back and forth, just when you think you have everything under control.”

Ending the pandemic will require vaccinating enough people worldwide to achieve herd immunity—about 70 to 85 percent of people, Fauci estimated. But while the vaccines currently available have shown good results in preventing infections, researchers have not yet concluded whether they prevent transmission. Until that is proven, Fauci said, the public will need to maintain precautions.

“The instinct is to say, ‘We have a really good vaccine. I'm vaccinated. I’ve had a 95 percent effective vaccine. Why can’t I do whatever I want to do,” Fauci said. “Ultimately you may be able to do that, but not right now, because there are things we don't know.”

At a time when many municipalities, including Chicago, are deliberating how and when to resume in-person instruction in public schools, Fauci said that teachers need to be prioritized in distributing COVID-19 vaccines. “The reason for that is the importance of getting the kids back to school, and we know that the teachers’ concern about getting infected is one of the reasons why the schools don’t open,” he said. “They’re a very, very important part of the population.”

Like the rest of the world, Fauci too is anticipating a time when the pandemic will abate and people can resume a more normal life.

“I'm looking forward to a number of simple things. My wife and I like to…go to a really nice, pleasant bar-restaurant up the block. We know the owners. We know the people. We sit down, we have a beer, we have a hamburger, we come home, and we go to bed. We haven’t done that in a year,” he said. “Part of the fun of natural living is interacting with society.”