Not even the Oracle of Delphi could’ve predicted the events of the past few weeks. Or maybe she could’ve. Who knows? Foresight doesn’t exactly seem to be a strength for our Greeks right now, but—in case you’ve been living under a rock, or on the off chance your trireme was wrecked by a storm—here’s a quick recap. A handful of major frat parties, held immediately after spring break, appear to have contributed to an outbreak of several hundred new cases of coronavirus on campus, prompting an emergency quarantine that suspended in-person classes and shut all undergraduate activities down for two weeks. Unsurprisingly, the backlash was swift, intense, and unrelenting. Petitions were drafted, posted, and shared; strongly-worded emails were sent; UChicago’s most popular public forums went up in flames. April was the month of the fraternity in the same way 2019 was the year of Cats: nobody liked it, nobody shut up about it, and nobody could get it out of their heads.

I, for one, have learned more about fraternities over the past five weeks than I expected to over the course of a lifetime. It’s like I took a crash course on the ethology of the elusive creature that is the fraternity brother. They don’t do particularly well in captivity, but go ahead—ask me how to catch one. You know how you prime a mousetrap with cheese? It’s like that, but the bait is a Natty Light. (Coors works in a pinch.) The natural habitat of the fraternity brother is a darkened basement, and it lives in large, tight-knit groups. They are unique in the animal kingdom in that every single member of their species is male, and were first identified as a unique species in 1776, in Williamsburg. See? I could teach a class on this.

Even taking several quarters of Hum and Sosc courses, however, has brought me no closer to figuring out one thing about fraternities: why frat life is called Greek Life. Maybe it’s because of the bacchanalianism of their parties, or maybe it’s because chapters look a lot like city-states. Maybe it’s because Greek letters look good on bomber jackets. Truthfully, I’m not sure. But in light of everything that’s happened in the wake of April’s frat parties, I figured it’d be worthwhile to try and figure it out. Welcome to the pilot episode of UChicago Fraternities: Are They Greek? How Greek Are They? Let’s Find Out!

When I try to compare how our frats managed a deadly, virulent disease to how the ancient Greeks might’ve, I can’t help but think of the Plague of Athens, which brought ancient Athens to its knees, ravaged its population, and killed a fourth of its citizens. Thucydides described the plague as being “so overwhelming that men…became indifferent to every rule of religion or law.” That’s a quote from a dead Athenian, but it could very well pass for a sentence pulled straight from an article in The Maroon. Faced with a plague that spread quicker than anything they’d ever seen, the Athenians responded by engaging in revelry and debauchery on an unprecedented scale. Even the notoriously unflappable Spartans (who were, at the time, laying siege to Athens) were so taken aback that they left the city to avoid infection. Think about that for a second. The Spartans, of all people, had the good sense to flee potential infection, while the Athenians—many of whom spent most of their lives philosophizing about rationality and morality—just gave up on both, in what might best be described as the very first Full Send in history: parties galore, consequences be damned. In that respect, the folks over at the frats are in good company (or bad company, depending on how you look at it). And in that respect, they’re undeniably Greek.

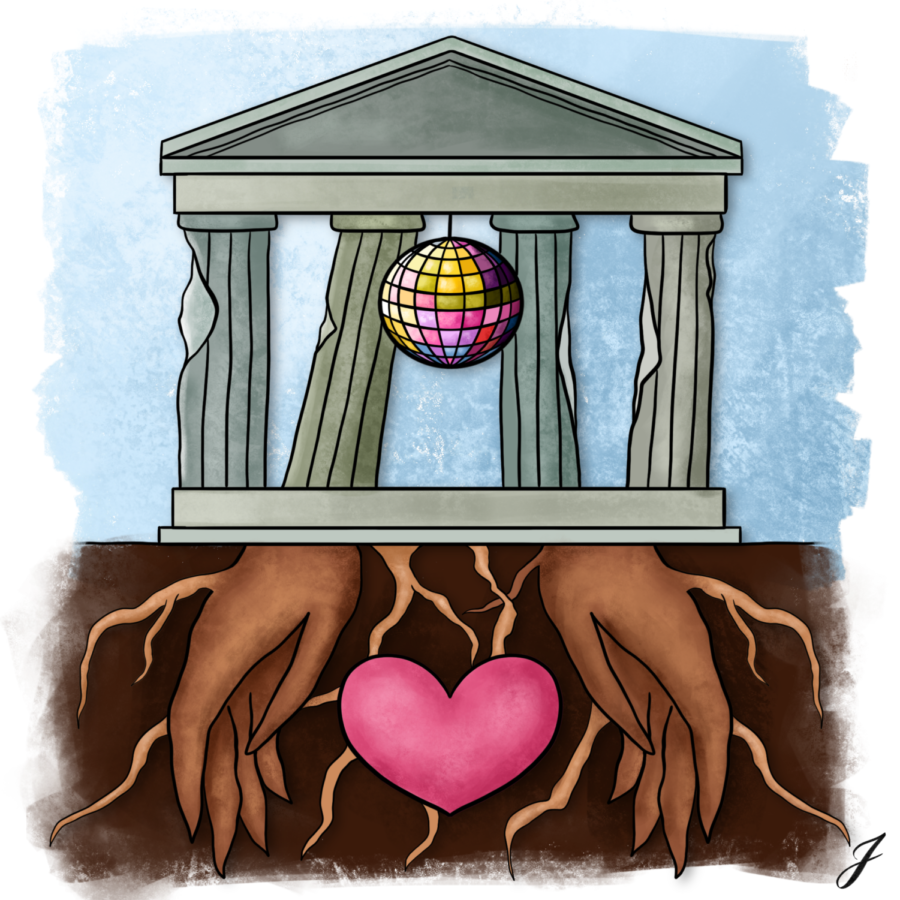

But here’s the deal: the ancient Greeks weren’t just raucous, wine-drunk pseudointellectuals with a penchant for flagrantly ignoring common sense, as Thucydides’ account of the plague might have you believe. The Greeks believed in accountability, and in serving their communities. They coined the term “philanthropy,” and used the word in its most literal sense. They consciously bettered the world around them. I’m not saying that ancient Greece was a socially progressive paradise; it was not. Neither am I saying that fraternities do nothing for their communities; in fact, I think they have tremendous social potential. What I’m saying is that they’ve fallen prey to rash and frequently destructive patterns of behavior which would’ve been anathema to the ancient Greeks (satyrs and maenads notwithstanding). Beyond the irresponsibility of throwing parties during a pandemic are more enduring structural concerns about fraternities; charges of institutional racism and misogyny are leveled at them on a regular basis, and they’re breeding grounds for exclusivity. And it’s time for an update. Even if Greek Life truly is Greek, it’s a way of life that’s never made it past 430 B.C. It reflects some of the worst aspects of ancient Greek life, and it fails to incorporate some of the best.

Don’t take this column as a call for the abolition of fraternities, because I’m not advocating for that at all. Instead, take it as a plea for change. Greek Life shouldn’t be an excuse for reckless endangerment. It shouldn’t normalize widespread sexual assault. It should promote the camaraderie it already does, but in a way that doesn’t promote it at anybody else’s expense—least of all the entire population of the college.

And while I’ve got your attention, here’s one last scruple I’ve got: beer. Beer’s disgusting, and the Greeks had a well-documented fondness for wine—so much so that they dedicated an entire god to it. You want Greek Life to be authentic? Go buy a Chardonnay. And for the love of Zeus, wear a mask while you’re at it.

Ketan Sengupta is a first-year in the College.