The nature of scientific discovery, as philosopher of science Thomas S. Kuhn would describe, is to re-evaluate collectively accepted notions of reality (paradigms) through research-based evidence to confirm or refute what was once accepted and is now being questioned. Progress follows crisis, and crisis follows the criticism of a system that is no longer sufficient.

So what happens when the system in need of re-evaluation is the social structure of science itself?

In the recent film Picture a Scientist, these questions are answered through the process of normal science, with evidence spanning from experimental data analysis to the research project that is the lived experience of women in STEM.

The film, directed by Sharon Shattuck and Ian Cheney, generated high praise and necessary discussion after premiering digitally last month, unveiling gender discrimination in the scientific industry that extends much deeper than the visible tip of the iceberg. This metaphor for an understated and rarely fully comprehended issue is one of multiple effective visuals used in the film to describe the depth of sexism as it infiltrates the scientific community.

Picture a Scientist commands the viewer to confront and question their preconceived notions of an ideal scientist using the titular exercise of asking the audience to “picture a scientist” as an introduction to an inquisitive and thoughtful documentary that intertwines the stories of three scientists with three core commonalities: their femininity, their subsequent discrimination, and their dedication to fight against it.

Jane Willenbring, an American geomorphologist at Scripps Research Institute of Oceanography and Stanford University professor featured in the film, investigates erosion and cliff retreat in coastal zones. Her work is reminiscent of the phenomenon occurring in the world of science through the growing number of women entering the field—as Willenbring studies the impact of rising sea levels on the geographic landscape, this film studies the impact of a rising class of female scientists on the demographics of academia. However, neither fieldwork nor a shifting landscape are glamorous in experience, especially not when faced with gendered harassment and discrimination, which, in Willenbring’s case, constitutes bullying, humiliation, and physical assault. While her daughter identified her as a scientist after seeing her in a white lab coat, the truly distinguishable trait of Willenbring’s scientific identity must be the intellectually curious and progressively driven habit of reporting her research. By filing a Title IX complaint, her discrimination became evidence to support the theory that nearly every woman in STEM can already confirm: in an industry mired in the mentality that only “the best will reach the top,” the systemic oppression of women will perpetuate their underrepresentation in medical fields until, and even after, its devastating impact is addressed. Systemic oppression of women will perpetuate their underrepresentation in medical fields until, and even after, its devastating impact is addressed.

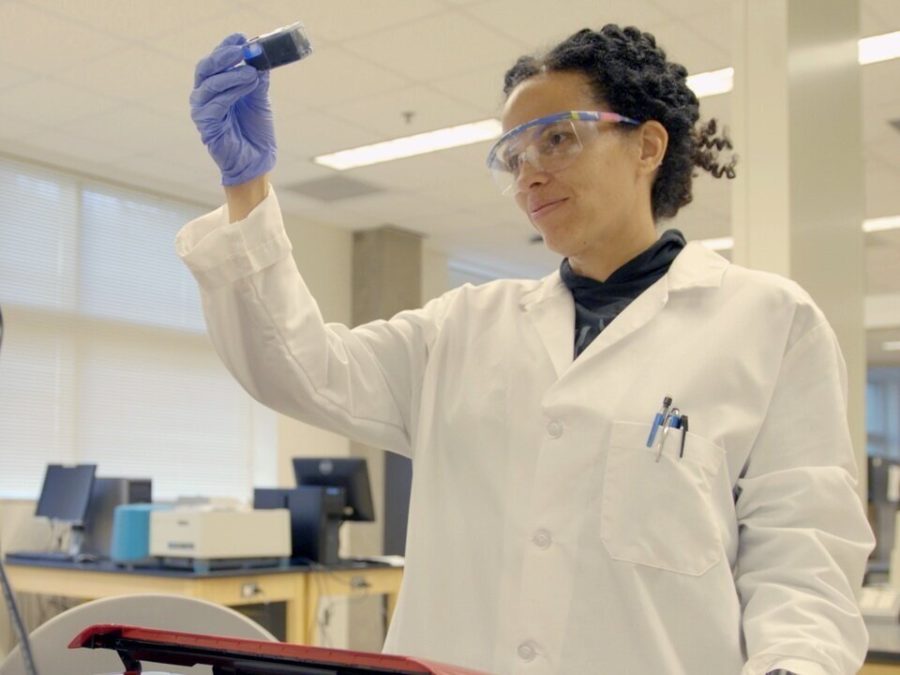

This notion is emphasized by the essential vocal presence of Raychelle Burks, another scientist featured in the film. Her impact follows her research as she identifies the most harmful elements of chemical compounds and responds to the challenges faced by a woman of color in her department. Discussing the importance of testing metrics, the viewer begins to understand the degree of her discrimination; one of the most dangerous parts of discrimination is its implicit nature, which facilitates the internalization of biases and normalization of their manifestations in victims and perpetrators. Burks’s experience with, and expression of, the biases she confronts on a daily basis exposes the human industry of science, which, in her words, “invokes both brilliance and bias”—but on the receiving end of a combination of racism and sexism involves a stark underrepresentation underlined by neglect, doubt, and deprivation of well-deserved credibility among a limitless array of micro- and macroaggressions. She is one of many scientists identifying these dangers to create a safer environment, which is especially crucial in her field as a woman of color.

Nancy Hopkins, whose voice carries the wisdom of someone who knows science well enough not only to live in its pursuit but to teach it, reminds us of the assumptions and associations of science and gender by saying “when you ask someone to draw a picture of a scientist, it used to be all men.” She extended her research into a dataset whose analysis provided evidence of the department denying equal space to her and her female colleagues. The supervisor refused to acknowledge the facts presented to him. But evidence, like a wildfire or justice, is imminent and unavoidable: it simply needs to spread far enough. The combined network of women in scientific academia who shared these experiences and overcame their fear of confirming stereotypes imposed on them, such as “weak” or “controversial,” assembled to confront the dean of the school of science and request data—but were nearly extinguished by the dissuading response they received, which denied the possibility of change by stating that the issue was “the nature of a male-dominated culture.”

But these stories do not forego hope—they inspire it. “We are creatures who learn,” says Mahzarin Banaji. Burks reminds us that “by nature itself, science should always be evolving.” And Willenbring’s data, when analyzed, proves to us that the cliffs really are reshaping. So, when speaking of paradigms, we might return to the Newtonian school of thought when considering what really happens when an unstoppable force meets what was once thought to be an immovable object.