This review contains spoilers for Squid Game, which is not about squids. Or even really about games. You’ve been warned.

I wasn’t going to write a review of Squid Game. While addicting enough to binge in one night, I found the show uninspired, bogged down by predictable side plots that meandered far too much and a main character that I didn’t want to root for but knew would survive to the end. Squid Game had nothing new to say.

But then everyone started watching it. Everyone had a meme to laugh over or an opinion to share. The show has now become Netflix’s biggest hit, overtaking Bridgerton and Lupin. Suddenly, Squid Game—or more accurately, people’s reactions to Squid Game—was something I could write a review about.

Squid Game follows 456 contestants through a series of deadly games modeled after common Korean childhood pastimes: Red Light, Green Light; Tug-of-War; the titular “Squid Game,” etc. The contestants compete for 45.6 billion Korean won, their ticket out of crippling loans they cannot pay back. Through its nine episodes, Squid Game uses its games to test the contestants’, and by proxy humanity’s, capacity for goodness. It’s a simple premise, emulating the psychological tensions of Japanese manga like Liar Game and Kaiji as well as the shock horror of iconic action-thriller Battle Royale. Take a group of people and isolate them: When they are in an environment beyond their control in which there are clear stakes, winners, and losers, their true natures will reveal themselves.

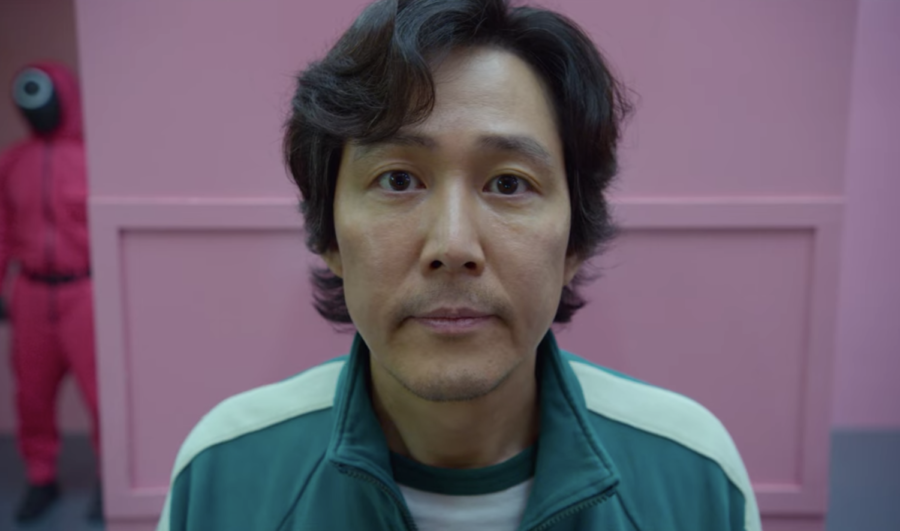

Of course, in Squid Game, these natures are all too easy to predict. Perhaps due to its massive cast and breathless pacing, the show resorts to shallow archetypes that allow little room for development. The Gangster (Heo Sung-tae as Jang Deok-su) is covered in tattoos, so he is evil, and he does things like push around The Young Girl. The Young Girl (Jung Ho-yeon as Kang Sae-byeok) is mysterious and a loner, so she gets a tragic backstory (North Korean defector looking to reunite with her family) to make us feel even more sympathy for her tragic death at the hands of The Best-Friend-Turned-Traitor (Park Hae-soo as Cho Sang-woo), a death which is then used to motivate The Main Character (Lee Jung-jae as Seong Gi-hun) before the final game. The Main Character is an everyman who both befriends weaker contestants and, when desperate for his life, tricks them: He shows how even the “nicest” among us often fall short of true goodness—and yet we should still be empathetic because it’s the Rich Beneficiaries of Capitalism that put him in this position. It’s difficult to sustain empathy without development, though. Gi-hun starts Squid Game as a terrible father and son, and he ends Squid Game as a terrible father and son. Squid Game’s characters are elevated by great acting performances (Lee, Park, and Jung are a standout trio), but most of them are little more than tropes.

The games themselves are exciting but unspectacular—contestants win through a combination of luck, prior knowledge, and physical strength (we’ll get to the marbles game and Anupam Tripathi’s brilliant portrayal of Ali later). Where Squid Game departs from tropes and transforms into something worth talking about is in the context of its games. As a critique of Korea’s hyper-capitalistic society, Squid Game never lets its viewers forget why exactly the contestants are so desperate. Episode two, aptly titled “Hell,” sees the players vote to end the game and go home—only to realize the hell of their lives outside the game and opt back in at the next possible opportunity. Squid Game suggests that the game’s organizers (the rich elite) control the contestants’ every move regardless of any “choices” given. It’s a clever analogy for the illusion of free will in a capitalistic society, which deludes the people at the top from seeing the havoc they have wrought on the people they have abandoned at the bottom.

Hyper-capitalism pervades even the meta of Squid Game. The show was shopped around for over ten years, with writer and director Hwang Dong-hyuk even selling his laptop at one point for sorely needed cash. It’s only due to Netflix’s massive investment in Korean media (around 550 billion won, or 500 million dollars, this year alone) that Squid Game was picked up (its more graphic scenes would have warned away most Korean broadcasters, which adhere to strict standards for what can be aired on Korean TV). It’s doubly ironic, then, that an investment from an American company led to a show critiquing capitalism in a society with a market structure defined by post-war American forces. Especially when the popularity of said show has drawn in a large American audience who have been eager to criticize Korea’s capitalism without considering America’s continuing role in it and for whom the show’s nuances and cultural inspirations have at times been ignored or deliberately misunderstood.

I should digress here to say that I’m not Korean, and I don’t speak or read the language. The Netflix subtitles for Squid Game are supposedly inaccurate (unsurprising, given the number of times they’ve botched other international media), but I don’t know enough to write about that. Even acknowledging the effects of incorrect contextual information, I’ve been disheartened by the amount of takes I’ve read on Squid Game that attempt to force it under a distinctly Western lens. There’s the “Squid Game is like The Hunger Games because it follows a battle royale format and also like this little-known Japanese movie Battle Royale” for people who don’t like East Asia, the “Squid Game is like Parasite because they both talk about capitalism and also because they’re both Korean” for people who watched the 2020 Oscars and don’t like East Asia, and, as excellently summarized here, the “Western viewpoint when analyzing honorifics as a survival mechanism [in East Asia]” for linguistics university professors who can’t be bothered to do basic research and don’t like East Asia. It could be due to the default prevalence of Western media on a global scale, but there’s a strange and depressing tendency to categorize East Asian media along Western morality and cultural lines—as with Vox’s Aja Romano consistently fetishizing Chinese historical fantasy epic The Untamed as a "queer romance novel.”

Still, while Squid Game has succeeded regardless of any cultural or contextual familiarity, it is at its best when it allows those nuances to work within the dramatic structure of a game. This can be seen in episode six, “Gganbu” (“trusted friend” in English), arguably the emotional climax of the show. Throughout Squid Game, the tainting of familiar childhood games with death acts as a metaphor for the destruction of innocence within society—a metaphor taken to the extreme in “Gganbu,” where the contestants are instructed to pair up and then take their partners’ marbles without resorting to violence. Contestants who are willing to trick their partners survive, betraying any lingering internal goodness and destroying the trust built up from previous games’ partnerships. And in the case of Sang-woo and Ali, betrayal is a stark reminder of the societal structures that exist even among those abandoned by society.

Squid Game’s Ali is an unfortunate and necessary examination of Korea’s treatment of migrant workers, who frequently face substandard housing, withheld pay, violent abuse and more. His use of honorifics and a deferential tone when speaking reflect his vulnerable position in Korea’s homogeneous society, so when Sang-woo indicates that Ali can address him as “hyeong” rather than “sajang-nim,” he replaces (but does not eliminate) their difference in status with friendliness. Ali repays this friendliness by trusting Sang-woo, ironically making him more vulnerable to the latter. Sang-woo knows he can take advantage of this vulnerability, but Ali does not: He dies because he believed he was winning their game—because he put his faith in the goodness of someone above him in the social hierarchy.

And that’s what society demands for goodness: It demands that we trust, again and again. It’s the central conflict of economic problems like the prisoner’s dilemma and manga like Liar Game. Yet in Liar Game, the innocent and “good” characters are allowed to survive because their goodness is protected by others—their trust is never betrayed when it matters most. Its focus is on the psychological twists unveiled within its games, protected by a narrative vacuum. In Squid Game, only Oh Il-nam (O Yeong-su) is protected.

I’ll admit, I’m still not entirely sure how I feel about the last-minute reveal of Il-nam as the evil mastermind. On the one hand, it reshapes his earlier kindness in a more insidious light (he was nice because he could afford to be nice) and drives home Squid Game’s point that games cannot exist within vacuums, as no playing stage is ever truly fair. On the other hand, it destroys Gi-hun’s only real source of character development: Not only does it ruin a relationship of mutual respect the writers had worked hard to build, but the plot twist also excuses Gi-hun’s malicious deception of Il-nam in “Gganbu” since Gi-hun was the one being fooled instead. So, while the message is there, the twist does feel a little too much like a twist for the sake of a twist since Il-nam says his speech and then dies right after, leaving Gi-hun and the viewers with no opportunity to develop.

Squid Game’s side plots feel similarly pointless, existing only to fill screen time and set up a future season (assuming police officer Hwang Jun-ho (Wi Ha-joon) follows the classic K-drama rule of not being dead unless a body is shown and maybe not even then). Actually, the reveal of Jun-ho’s brother (Lee Byung-hun) as one of the game’s front men is so predictable that without having watched a single episode, my mom guessed it after being told “the side plot is the police officer looking for his missing brother.” Meanwhile, the foreign VIPs are disgusting, but in that ridiculous way where they’re disgusting just to be disgusting and jar the viewer out of the show whenever they’re on screen, and the organ trafficking…happens.

Squid Game’s weaknesses—that the games are predictable and that everything outside of them feels contrived and boring—are ultimately what make discussing the show so fascinating. The show asks its viewers, over and over, to consider how our definition of “good” can transform, yet coverage forcibly separates Squid Game reviews from articles on the show’s contextual history. So I find myself wondering the same thing of Squid Game: Do its questions about “goodness” change with how people have interpreted them?

I began this review by saying Squid Game had nothing new to say. It’s also accurate to say I have nothing new to say about Squid Game. But Squid Game tells us that games cannot be divorced from their environment and that events cannot be isolated from their contexts, so let’s talk about Squid Game—and let’s talk about why we’re talking about Squid Game.