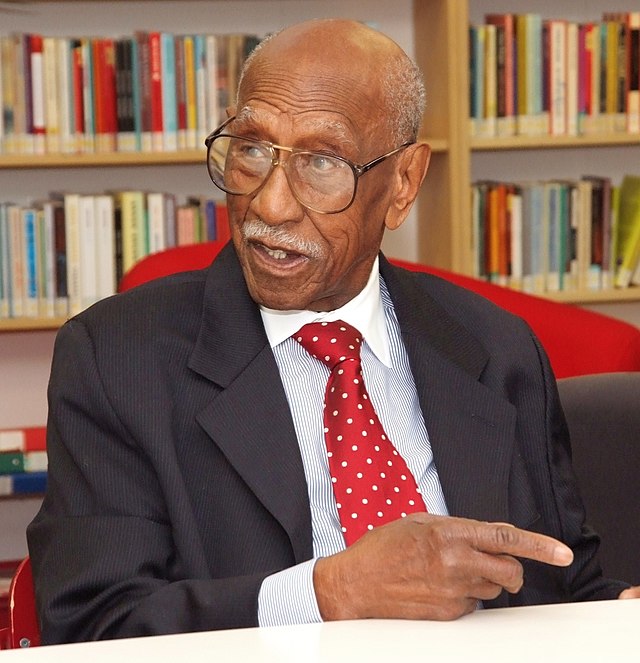

Timuel Dixon Black Jr. (A.M. ‘54) was living history from the moment he was born. His family moved from Birmingham, Alabama up to Chicago as part of the first Great Migration, when Black was just a few months old. But as the family joke goes it was Black who instigated this change: he looked around at the oppression taking place in Birmingham, and said, “Shit, I’m leaving here.” All his parents could do was get on the train with him.

I still remember the first time that I met Black, in my first week at UChicago, right before he turned 100. He was leading a tour of Bronzeville for incoming UChicago students organized by the Civic Knowledge Project (CKP). As we drove around the South Side, a place Black referred to as his “Sacred Ground,” he said to us “A Change is Gonna Come,” quoting the lyrics of Sam Cooke—whom he knew personally—to which he added, “so where will you be when it does?”

Black’s answer to this question was clear: on the front lines, fighting for justice and making history. He is remembered as a father, husband, friend, teacher, mentor, historian, war veteran, jazz enthusiast, labor organizer, activist, and one of the most important leaders of the civil rights movement in Chicago. He leaves behind a legacy of commitment to social, economic, and racial justice that has inspired generations of students and activists in Chicago and beyond through his example, stories, and lessons that we could not learn in a classroom.

Black was born in Birmingham, Alabama on December 7, 1918, to Mattie McConner Black and Timuel Dixon “Dixie” Black, a steel mill and stockyard worker. All four of Black’s grandparents were enslaved. The Black family moved to Chicago in August 1919, a few weeks after the Chicago Race Riot. Their first house was on the 4900 block of St. Lawrence Avenue. The family moved frequently, but, as he says in his 2019 memoirs, Sacred Ground, “it was all in the same close community—Bronzeville, the Black Belt.”

Black graduated from DuSable High School, 4934 South Wabash Avenue. This school deeply shaped his intellectual trajectory. DuSable, he wrote, was “the first school that really felt ours. I felt at home there. I was able to excel and so were many others.” Built in the 1930s, the school’s construction was part of an effort by the school board to ensure that Black students did not transfer to schools in white Chicago. Carved over the auditorium stage were the famous words of abolitionist Wendell Phillips, “PEACE IF POSSIBLE, BUT JUSTICE AT ANY RATE.” This school motto would stay with Black for the rest of his life.

The Great Depression hit Chicago when Black was a young boy. But alongside hardship came solidarity with his neighborhood community. As he writes in his memoirs and often recounted, “It was the Depression but we were not depressed. There was poverty, but we were not poverty-stricken. We took care of each other.” As a teenager, Black began working at a grocery store where his older brother used to work, on 51st Street between Indiana and Michigan Avenue. Here, he met J. Levert “St. Louis” Kelly, who helped him and other workers organize to form the Colored Retail Clerks Union. Through this activism, the group secured a raise from $12 to $18 per week.

Black was already politically active in his teens and early twenties. In addition to labor organizing, he used to discuss politics in pool halls—including Dad’s Very Safe Pool Hall at 51st and Indiana, where Richard Wright also used to go—and frequented political forums at Washington Park, where Black used to listen to Communists Claude Lightfoot and Ishmael Flory speak. Black’s support of Flory would later cost him a spot in the Officer Candidate School while he was in the army.

He was working for the Metropolitan Funeral System, selling funeral insurance policies, and succeeding as a salesman when global events changed the course of his life. In 1940, Congress passed the Selective Service Act and, one year later, as Black was celebrating his twenty-third birthday, on December 7, 1941, Pearl Harbor was bombed. When his draft notice arrived, he sent it back saying, “I don’t have an uncle named Sam. My uncles are named William and Walter.” Unlike many who have laughed upon hearing his stories, the US military did not share Black’s brand of humor. He joined the army two years later, in August of 1943.

The war years left Black with a sober recognition of the horrors of injustice. He served in Europe and marched down the Champs Élysées on August 26, 1944. Following the Battle of Bulge, he visited the German town of Buchenwald and went to a concentration camp, where he saw firsthand the atrocities of the Nazis. “I was so hurt, so angry, that I began to cry, and my first priority was to kill all the Germans,” he remembers in his memoirs. “Then I began to realize that some of our soldiers were of German descent—even Eisenhower, Eichelberger, you can go on and name them. This got me reflecting, and I thought, this can happen anywhere to anyone.” All of this occurred while he served in a segregated army, where he faced and observed daily racism and hatred against soldiers of color from fellow white soldiers and officers. These experiences shaped how Black saw the racially segregated United States upon his return home. In his words, “it was the beginning of something new.”

After serving in the army, Black enrolled in Roosevelt University followed by graduate school at the University of Chicago, where he earned a master’s degree in 1954. He studied sociology and history at UChicago under Allison Davis, the University’s first tenured Black faculty member. in 1955, Black had completed all the work required for the doctorate except for his dissertation when he watched Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. give a speech on TV. King’s message spoke to him so deeply that he got on a plane to Montgomery that weekend. At the time, he was also working as a high school teacher at his alma mater, DuSable High School, and at Roosevelt High School in Gary, Indiana.

In 1956, Black helped bring King to Chicago to speak at his church, the First Unitarian Church of Chicago, at 57th and Woodlawn. The space could not fit the crowd that came to hear King speak, so they had to move to Rockefeller Chapel—which still failed to fit the crowd. During the late 50s and early 60s, Black commuted between Alabama and Chicago frequently, supporting King’s movement. The two men would become close over the years—King called Black “TD,” and Black called King “Doc.”

Black embraced the shared ends and tactics of the Civil Rights and labor movements. Around 1960, A. Philip Randolph had challenged the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) about segregation in unions. The organization’s racism at the time propelled Black and labor organizers to found the Negro American Labor Council. Black became the local president of the NALC and stayed active in labor organizing during these years. It was Randolph who first proposed the 1963 March on Washington, but he asked King to take over its leadership because of his international reputation. However, the labor roots of the March remained greatly apparent in Chicago, especially after King and Bayard Rustin, the political strategist behind the March, tasked Black with mobilizing the Windy City. With the help of many volunteers, civil rights, and labor organizations, Black and other leaders, like Larry Landry and Charlie Hayes, saw to it that Chicago had a strong presence in Washington. They led 3,000 people by train, and a total of around 4,000 Chicagoans marched in DC in August 1963.

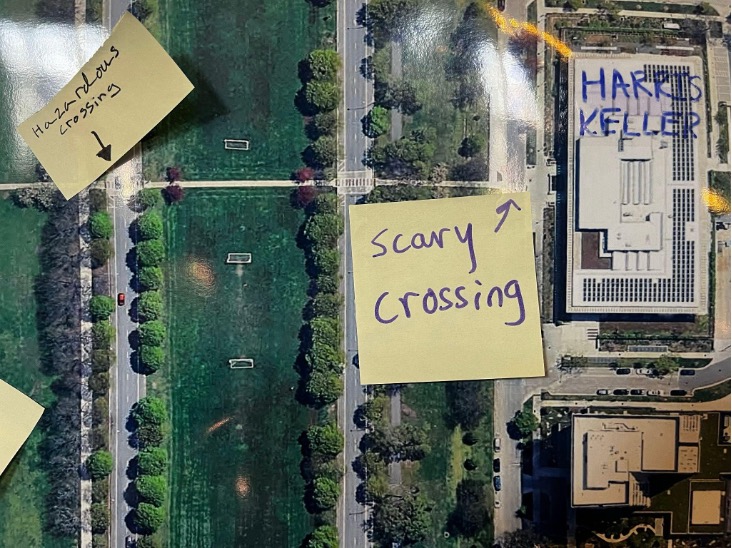

Black also took a shot at running for office in 1963. He was part of a campaign against the “Silent Six,” a group of Black aldermen who were part of Mayor Richard J. Daley’s political machine. Black lost his race, but nevertheless remained a significant player in the struggle against the Chicago political establishment and its racist institutions. Later that year, he was involved in organizing a mass protest against Daley and Chicago Public Schools Superintendent Benjamins Willis, who was responsible for the infamous “Willis Wagons,” portable classrooms placed in the playgrounds of schools in the South Side to prevent Black students from transferring to white schools. It was then that Black coined his famous slogan, “end plantation politics.” He would also run for a seat in the Illinois House in 1966 but withdrew after a change in rules in the electoral procedure.

Black’s fight against the Daley political machine continued into the early 80s, when he played a central role in rallying voters, especially Black voters, to elect Harold Washington, Chicago’s first Black mayor. Black knew Washington personally and worked with him closely during his campaign.

In 1992, Black witnessed yet another historic moment in the movement for racial and gender equality when Carol Moseley Braun won her seat as the first Black woman to serve in the US Senate. She was also from the Sacred Ground of Bronzeville. In fact, Black’s wife Zenobia was close friends with Braun. And so, although they disagreed on some political matters, Black strongly supported her. Braun unsuccessfully ran for the Democratic presidential nomination in 2000 and in 2004. In his memoirs, Black wonders how things would have been different had the nomination turned out otherwise: “I cannot help thinking about just how historic it would have been if the first Black president of the United States had also been a woman, a woman from my Sacred Ground. Carol could have done it. Could have been, should have been.”

Black was a celebrated teacher and beloved by his students. As an educator, he always worked for the advancement of young Black people, especially those whom others did not believe in. He taught at DuSable High School, his alma mater, before working at Roosevelt High School in Indiana. He later taught at Hyde Park Academy High School, Wright Junior College, and Loop College, which is now Harold Washington College. Black officially retired in 1989, but, as he liked to say, “I am retired, but not tired.” He continued to be an educator and scholar for many years, mentoring young people and instilling lessons in generations of students to come. In fact, in his “retirement,” he produced two volumes of oral history, Bridges of Memory, detailing the stories of Black Americans who moved to Chicago during the first Great Migration and their children. In 2011, the Oral History Association gave him an award and described Bridges of Memory as a “people’s history of Chicago.”

Among Black’s many mentees was future president Barack Obama, who, having recently graduated law school, asked Black to meet him in 1992. They met at Medici on 57th Street. “He was a talented young man who was going to be ready when the doors of opportunity swung open,” Black recounts in his memoirs, “But he had a lot to learn. And I mean a lot.” Black attended Obama’s Presidential inauguration in 2008, which he remembers to be “as magical as the March on Washington.” Although he remained a supporter of his, Black did not stay quiet during Obama’s presidency and often sympathized with Obama’s left-wing critics.

When Black passed away on October 13, the former President released a statement remembering him. “Today, the city of Chicago and the world lost an icon with the passing of Timuel Black.” Obama continues, “Over his 102 years, Tim was many things: a veteran, historian, author, educator, civil rights leader, and humanitarian. But above all, Tim was a testament to the power of place, and how the work we do to improve one community can end up reverberating through other neighborhoods and other cities, eventually changing the world.”

Black called the South Side communities that make up the Black metropolis his “Sacred Ground.” He wanted others to know of it, and he recorded many of its stories in his memoirs and oral histories. For many years, Black collaborated with Dr. Bart Schultz and the University of Chicago’s Civic Knowledge Project (CKP) to share Black’s record of this Sacred Ground with others. In his memory, the CKP has established the Timuel D. Black Solidarity Scholarship Fund to support UChicago students committed to carrying on the legacy of Timuel D. Black.

In a June 2020 interview with the Chicago Magazine discussing the wave of Black Lives Matter protests following the death of George Floyd, the interviewer asked, “How [do] you see the strife ending?” Black responds, “Let me put it this way: I’m glad I’m not a teenager, because they don’t feel as optimistic about the future as people of the earlier generations did.” Black, a man who came to Chicago during the 1919 Race Riot and saw firsthand the horrors of Nazi concentration camps, devoted his life to peace and justice. For those of us who had the opportunity to listen to him tell his stories—which he often recounted with humor—he radiated hope: a hope that taught us, like he used to say, how important it is for us young people to listen to our elders.

A public memorial service will be held on December 5 at Rockefeller Chapel. He is survived by his daughter, Ermetra, and his wife of 40 years, Zenobia. He was 102.