This academic year, students found themselves welcomed by emerald green trees, the scent of freshly-ground coffee permeating the warm air, and swarms of their peers walking through the picturesque main quad. While walking through these swarms of students, I couldn’t help but think about how—after over a year and a half of isolation, uncertainty, and death—the liveliness of campus life felt jarring. Despite the collective excitement of being on campus, it feels strange to return in the middle of a pandemic that’s far from over. Of course, it’s always pleasant to catch up with friends—and finally be able to meet classmates I’ve only seen on tiny, scattered Zoom screens—but despite the allure of an attempted return to normalcy, it’s reckless to ignore the reality of a pandemic that continues to tear through communities across the country.

When we were forced online last March, we assumed that it would be a temporary situation. A year later, it’s clear that COVID-19 is here to stay—a facet of life that forces us to constantly adapt to evolving circumstances, restrictions, and regulations. Here’s the issue: professors, student organizations, and students on campus haven’t quite acclimated to that adaptation. In refusing to accommodate students experiencing symptoms of COVID-19—or, for that matter, any illness—professors and RSOs with attendance requirements create an environment that’s both unsustainable and hostile. In many classes, for example, attendance comprises a significant portion of a student’s grade, and we are only given a limited number of passes, as if we could plan how many times a quarter we get sick. Students shouldn’t be penalized or stigmatized for wishing to miss classes or meetings because they’re feeling physically unwell. We must all be more flexible with students who choose to miss school or events if they’re sick because—as the thousands of posters papered across campus would have you know—we’re all in this together and have a responsibility to make our community feel safe and healthy for everyone.

As much as students try to make the return to in-person classes feel normal, it feels anything but normal for those of us who’ve been afflicted by COVID-19—and have had the tragedy and senseless loss of the pandemic affect our own families. This side of the pandemic isn’t comprehensible for everyone, many of whom had the privilege of living normally while COVID-19 disproportionately impacted and devastated disadvantaged communities. Economically disadvantaged students, for instance, rely on UChicago’s Student Wellness Center for free comprehensive services, such as COVID-19 testing. Now, we’re at the mercy of Student Wellness’s often-crowded schedule and frequently expensive procedures—because going outside of campus to seek healthcare is costly not only because of transportation fees, but because insurance may not always cover it. As a result, some of us may have to miss class or important meetings based on whenever the next available appointment arises. As a student who has experienced these difficulties firsthand, it worries me that there aren’t nearly enough professors willing to accommodate students who choose to miss class because they’re experiencing symptoms.

I know that UChicago is a rigorous environment and that being a student here entails working long hours and late nights, often to the point of exhaustion. None of that discounts the fact that we’re in the middle of a pandemic in one of the largest, most populous cities in the world; an accessible, flexible approach to work helps us foster an environment that works for everyone—because everyone deserves a community that they feel comfortable existing within.

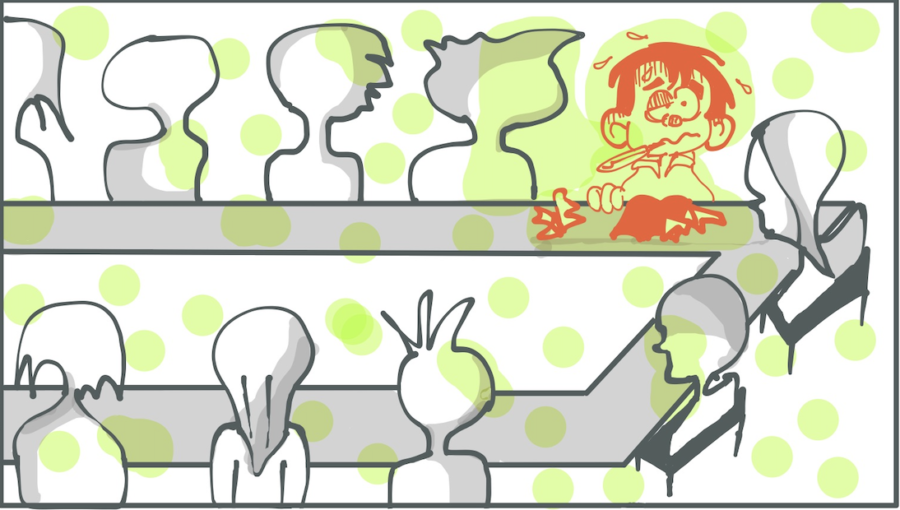

Two weeks ago, I missed my first class of the quarter because I was experiencing symptoms and wanted to get tested for COVID; in typical UChicago manner, I felt dread, not relief. Although I’ve been fortunate enough to have some flexible professors and TAs—with one of my professors having a Zoom meeting option for students who are feeling unwell, and another electing to upload all recorded lectures from past classes—not all professors are as accommodating, and some go as far as to penalize students for missing class. Spanish 202 professors, for one, only allow students to miss two classes without a penalty—and anything beyond that results in an immediate 3% drop in their class grade per absence. The class I was forced to miss, on the other hand, allows students a single absence per quarter, and I woke up violently ill that morning and knew that I’d have to use it. I get sick frequently, so I contemplated if it was even worth missing class that day because missing more than one would cause a deduction in my participation grade. As students, we’re all told to not miss a class unless we can’t bring ourselves to get out of bed; on top of having to suffer through classes while being sick, missing even a single session sets us back on what feels like several weeks’ worth of material. Consequently, we are constantly forcing ourselves to attend in-person classes, despite feeling physically unwell.

There’s plenty of discourse surrounding whether sick students should attend classes, from UChicago Secrets posts to frustrated rants overheard from across the quad. This discourse, however, should be centered on how we can all work towards making campus, and our surrounding community, a safer and healthier environment. Because while it may appear to be completely harmless to attend classes while sick, you are putting others at risk for COVID-19 if you do not get tested beforehand (if you are experiencing symptoms, getting tested is part of the Student Attestation form we all signed before coming back to campus).

Students, of course, are not the only group that need to be wary of their actions; it also relies on a professor’s willingness to be more flexible. In order to make sure we’re all moving forward as a community, it’s vital that we all remain conscious of how our actions affect one another. As we all know by now, while the mandatory mask mandate provides some form of protection, it’s just one layer of insurance; the success of our COVID-19 program relies on student accountability and professor adaptability.

Jennifer Rivera is a third-year in the College.