A young man seated one table away, directly across from me, is having a passionate-yet-clamor-distorted discussion with his friend––an upbeat young woman with strikingly purple hair. The young man’s plate consists of a pseudo-Pisian tower of semi-trapezoidal onion rings accompanied by some indescribable substance slathered in what I hope is barbecue sauce. The young woman, observing, has a sole, mostly yellow banana, lying limply on the table. A knoll of Lucky Charms sits comfortably between them. Dry, and seemingly untouched. Another person in a plaid shirt walks past me, wearing a Ushanka indoors and brandishing another mostly ripe banana in the same way that a prepubescent child might brandish a toy firearm. A friend of mine, grinning as he always does, approaches my table and greets me. We engage in approximately forty-five seconds of mutually enjoyable banter before he ventures off to find his other companions. By my count, his plate holds four breadsticks arranged in the fashion of a collapsed tipi, along with a generous portion of marinara sauce disproportionately distributed atop the highest layer. Speaking of breadsticks, the young man had briefly left the table but has since returned with two breadsticks of his own. The mostly ripe banana remains untouched. Such is the social condition of Fourth Meal at the Arley D. Cathey Dining Commons. At least in the region directly parallel to the chocolate milk station and perpendicular to the disappointingly not-ignited “Flame” Station, which should really be called the Dad’s Food at a Quintessential American Barbecue Station.

Originally, I came to this Fourth Meal planning on writing a Sinclair-esque hit piece on the grotesque nature of Fourth Meal and the food that UChicago students eat after a long day of almost intentionally obtuse philosophy courses and downright Sisyphysian problem sets. But as someone who has constructed his fair share of tater tot towers and eaten more bowls of Cosmic Cookie ice cream than I would dare to admit in a public forum, I came to the swift realization that this critique would be as out-of-touch as it was unfair. Instead, in the spirit of rigorous inquiry, it seems pertinent to explore underlying factors that determine what and when the typical UChicago undergraduate chooses to eat.

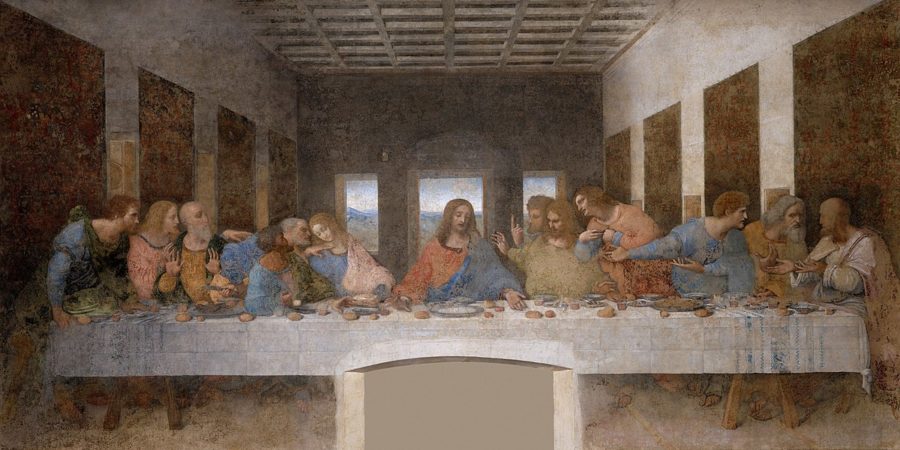

It is undeniable that the act of eating, at least to a moderate extent, is a social phenomenon. Humans have been congregating in feast-style gatherings for at least 12,000 years, and nearly every culture has its own customs, traditions, norms, and taboos associated with the preparation and consumption of food, among other aspects of the overall dining experience. Unsurprisingly, Fourth Meal is as much of a social experience as it is a dining experience for all participants. This might seem like an exceedingly obvious characteristic to point out, but Fourth Meal seems much more explicitly social than its First, Second, and Third counterparts.

Particularly, Fourth Meal is the social antithesis of breakfast. There are certainly groups that tend to congregate in the wee hours of the morning and have a pre (or, for some poor students, post)-lecture chat over healthy servings of scrambled eggs and whatever variety of American breakfast carbohydrate is available that day. However, I notice significantly more “islands” during conventional breakfast hours. That is to say, people sitting by themselves either reading, doing some form of homework on a computer that is completely indecipherable to a layperson, or simply enjoying their own company. There is nothing inherently wrong with being a social island, of course, but the nine o’clock archipelago gives breakfast a bit more of a socially depressed feel, comparatively speaking.

Lunch and dinner are a slightly different story. There seems to be a direct correlation between time passed over the course of the day and the general willingness of the student body to socialize at meals. Lunch is usually the second most raucous meal of the day, serving the function of a refuel after the first class or two of the day along with a functional midpoint through which people can exchange ideas, gossip, or P-set answers (but you didn’t hear that from me!). But the social climate of lunch is more akin to a trough than a get-together. House tables are packed shoulder to shoulder with people, many of whom do not, have not, and with all likelihood will not interact in a socially relevant capacity at the conclusion of lunch hour. Sure, there are discussions, hence the tumultuous nature of the thing, but they serve as marginally more socially intimate equivalents to those lame icebreaker discussions everyone had to endure throughout O-Week. Over the course of a typical 30-minute lunch at a UChicago dining hall, a privy observer can learn about Hegel, Hot Wheels, and who’s been sleeping with whom without much eavesdropping at all. These three topics could all be addressed by the same group of two to four people. There is approximately a 25 percent chance that none of them know each other.

Dinner seems to be the most evenly distributed of the dining hours from a social sense. That is to say that the Group, the Trough, and the Island are all prominent fixtures at any UChicago dinner table. There are the Groups, of course, that congregate after a long day of classes to discuss the revelries of the day. As a consequence, there are the Troughs, those who merely wish to congregate with a group of people to voice their complaints or share their morsels of gossip. And as is the case with breakfast, there are the Islands, although far more dispersed than the early morning Archipelagos. However, there is one social group that almost exclusively exists in the dinner setting alone: the Dyad. As the name implies, a Dyad refers to any social gathering of exactly two people, the bare minimum prerequisite for an event to be considered a gathering. The reason I refer to this structure as a Dyad as opposed to something like a Couple or a Pair or a Twosome is because the inherently romantic connotations of these three terms do a disservice to the complexity of their nature. There are your fair share of couples, sure, but among the Dyads are prospective couples, confidants, friends, ex-couples, and a myriad of other dynamics. Because of this concentration of Dyads I will make the contention that dinner is the most socially intimate of the four meals, if you want it to be.

Of course, there still remains the elephant in the room: Fourth Meal. Fourth Meal more closely resembles the pit of the Globe Theatre than any sort of conventional dining forum. Students from all across campus pour into the dining hall with reckless abandon, hands full and stomachs empty, ready to gorge themselves on pasta and the intellectual capital of their peer group. There is a sort of unquantifiable groupthink that governs the hedonism that seems so inherent to Fourth Meal. Grab a plate. Eat whatever. Live Now. Live Fast. Die Young. No earthly congregation comes closer to fulfilling the desires of Bacchus than the Arley D. Cathey Dining Hall at 11:30 on a Wednesday night. It is a personification of gastronomic pandemonium that would make any self-respecting dietician claw their eyes out. But why? What is the root cause for these desires? This collective caloric madness?

“I fought wild beasts in Ephesus with no more than human hopes, what have I gained? If the dead are not raised, ‘Let us eat and drink, for tomorrow we die.’” — 1 Corinthians 15:32

Fourth Meal, more explicitly than any other undergraduate dining experience, encapsulates the social condition of the University of Chicago. It exists as a function of the need for students to pull off legendary study sessions or cram encyclopedias of information in order to stay on top of coursework. It is a time to release your inhibitions and eat as much as whatever you damn well please. It is a time to fill your body with “nutrients” to help keep the all-nighter going. I would also estimate that a nonzero quantity of the most major discoveries and contributions made by UChicago undergraduates were made under the influence of some combination of dining hall pizza and 5-Hour Energy. It’s common knowledge Nobel Prizes are made out of talent, ambition, and more than a few slices of Macaroni and Cheese Pizza.

This is the slice of Red Velvet cake that will either spark paradigm-shifting discoveries or will serve as the catalyst for the hedonism-fueled downfall of modern academia. It’s 11:33 p.m. on a Monday, and I have just consumed a brick of sugar and cream cheese icing with a comically oversized fork in a clamorous hall populated by the ephemeral voices and ideas of some of the most brilliant young people in the world. It is at this moment that I am the lone Island in a sea of ingenuity. Whether they are Dyads or Groups or Troughs or among the legions of the Faceless Nameless shuffling back and forth between their respective seats at the table and the self-serve pasta station, these are people energized by the night and powered by some combination of carbohydrates and raw unadulterated willpower. We are shoulder-to-shoulder with greatness, and we all know the same grind and love the same grain. I used to think there was no place for cake after sundown. He who feasts everyday, feasts no day, yet those who do not hope to reach the feast will live their life without awe. To indulge in the Red Velvet is a microcosm of the human condition. Is it a risk worth taking, to reward yourself for your hard work? Or should the intrinsic value of your personal enrichment be sufficient compensation? My plate is clean. I know the answer.