Tenure began in the 1600s to protect unorthodox thought at religious colleges and entered the mainstream in the 1900s to bolster general academic freedom. Once professors have been rigorously vetted—a seven-year process on average—they earn the status of tenure with all of the privileges it entails. In this way, universities and colleges can select and retain highly qualified faculty while simultaneously ensuring their intellectual protection, or so the traditional justifications go. However, it's time to dismantle tenure, a system that in reality disincentivizes quality teaching and stifles institutional diversity.

The tenure system has been crumbling for decades. In 1969, 78 percent of instructional staff at US institutions of higher education were either tenured or in tenure-track positions, whereas in 2016 a mere 27 percent held tenure-track positions. Tenure-track faculty members now represent a small class of academic nobility, with the rest of academia relegated to lower-paying jobs.

Even for the minority who do end up in tenured positions, there are fundamental flaws in the tenure-granting process that impede quality teaching at research institutions. When a professor is hired into a tenure-track position, they are expected to teach, conduct research, and do service (i.e. mentor students and serve on committees). Yet, professors are almost always expected to perform these duties under a clear hierarchy. One tenured UChicago professor—who has taught at two other top research universities and wishes to remain anonymous due to fear of retribution in the internal promotion process—describes common advice from department heads and senior faculty members: “They will say that [research] should be your priority, not teaching, not doing additional mentoring…you know, do enough to make it appear on paper, at least, that you’re doing your job in terms of teaching but don’t go crazy.”

And when teaching quality is taken into consideration during the tenure granting process, this almost always is accomplished entirely through student evaluations. While important to consider, student evaluations are a far better metric of student satisfaction than teaching quality, as, intuitively, stricter professors or those teaching challenging content generally fare worse on student evaluations regardless of how well they actually teach.

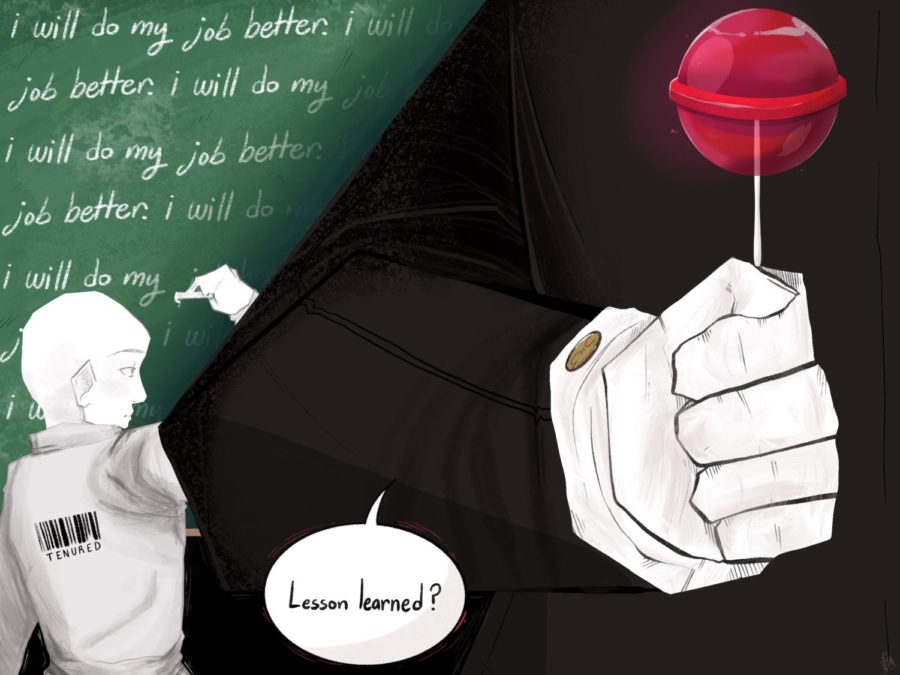

Once tenure is finally granted, professors face a massive structural shift in priorities. Of course, the profession selects people who genuinely care about teaching students, performing research, and the other responsibilities that follow. But after tenure is granted, there’s essentially no accountability to ensure high levels of quality in teaching, research, or service. The same UChicago professor I spoke with recounts that at another top research university, professors who receive particularly negative student evaluations are required to write a one-page paper about how they will teach better in the future and face no other incentive to teach well or punishment for not doing so. These professors may as well write “I will do my job better” a hundred times on a chalkboard. Low-quality research, teaching, or service will certainly prevent further internal promotions, increases in pay, title, etc., but, short of gross incompetence or highly immoral behavior, tenure makes the firing of faculty members effectively impossible.

An increase in diversity rates would likely follow the abolition of tenure. Aged faculty members, few of whom self-identify as minorities or women, predominantly occupy more senior positions with greater institutional influence. Universities commonly cite the high diversity rates of their incoming faculty members, but these numbers are incredibly misleading when seen in their full context. Take Stanford, for example. In September of 2020, an article published by the school boasted that “Stanford welcomes diverse group of faculty for 2020-21,” citing the 40 women and 51 men recently brought on-board. Yet the diversity report on total faculty members published in the same year tells a vastly different story, with 30 percent of total faculty members identifying as female, 15 percent identifying as neither Caucasian nor Asian American, and just 2 percent (50 people) identifying as Black or African American. A great number of aging faculty members who have effectively no required standard of quality for their jobs occupy positions that could be used to bolster the position of minorities and women at institutions of higher education.

The severe limitations of the ability for tenure to protect the free speech of professors––one of the most cited reasons for why it is necessary––have come to light in recent years. The most blatant example of this is the case of Bret Weinstein. In 2017, Professor Weinstein objected to a ‘Day of Absence’ in which white members of the Evergreen State College were “invited to leave the campus for the day’s activities.” After raising objections to this invitation in an email to all staff and faculty, Weinstein’s email was published in the Cooper Point Journal, the Evergreen State College student newspaper, which resulted in a series of protests directed at him. As a result of these protests, during which the president of the college allegedly instructed the chief of the campus police department not to protect Weinstein should violence break out, Weinstein and his wife were pressured to resign from the college. Because Weinstein was not fired, his speech was still nominally protected by tenure. Therefore, this is not a case of tenure being implemented poorly, but a demonstration of the foundational limitations to which it can be used to defend the free speech of faculty.

Of course, there are other threats to the free speech and inquiry of academics. Most notably, there were multiple instances of efforts by the Bush administration to suppress research that demonstrated the full extent of climate change. Yet I believe that we may prevent such instances from occurring while still dismantling the failing tenure system and increasing faculty accountability.

Academia without tenure will need to be founded on the continuous and rigorous assessment of faculty: quality in research, teaching, and service. Due to the vast differences in expectations for the amount and kind of work being done by faculty members across different disciplines, career stages, institutions, etc., such assessments will need to occur in a qualitative, peer-based manner. The way that research quality is currently evaluated at universities falls somewhere on the continuum of quantity vs. quality. On one end, professors are encouraged to publish as frequently as possible, regardless of the status of the publication. On the other hand, the prestige of the journal in which one’s work is published is far more important. According to one UChicago professor I spoke to, professors at the University are expected to publish a high number of articles in high-status journals. The specific context of a professor will need to be considered to arrive at a fair quality assessment.

Given the specific context of a professor, a fair assessment of quality can be arrived at through one’s peers.

Some likely view the prioritization of research over teaching quality as necessary to produce groundbreaking research. And while this may be true to an extent, professors without the designation of ‘research professor’ are hired to do more than just research. Universities may, and commonly do, decide to exempt professors who produce phenomenal research from large course loads or high requirements for teaching quality, according to one UChicago professor I spoke to. But this process would be made far more transparent through the thorough and homogenous evaluation of faculty members. Administrators might still decide to allow teaching exemptions for certain faculty members, but students could simply decide not to take courses taught by such professors.

Regarding teaching quality, many possible frameworks have been put forth as to how professors may be evaluated beyond student feedback. One includes measuring such varying indicators as “Knowledge and enthusiasm for subject matter,” “Skill, experience, and creativity with a range of appropriate pedagogies and technologies,” and “Understanding of and skill in using appropriate testing practices.” These factors may already play a role in the evaluation of professors in an à la carte manner with varying frequencies of implementation across institutions and departments, but if tenure is to be abandoned, a robust and hegemonic framework to evaluate teaching quality, covering the examples above and more, will need to be developed and implemented. Regarding service, it’s easy for professors to half-heartedly serve on a committee or two and adorn their CVs with an extra line indicating their commitments. But true service to the academic community is more difficult to gauge, and peer review will also be necessary to determine how thorough one’s commitments truly are.

If it sounds like the obligations and expectations I’m setting forth for faculty members are exorbitantly high, then you may not be appreciating the work that goes into being a competent professor. Each domain of their work could be a job in and of itself. But if we apply the same rigorous standards across the board, it will be easier to set expectations, praise, and remediation appropriately. Many may find out that they’re not suited for the teaching profession, and after their thorough evaluation and justified termination, the academic community will be better off. The way educational institutions evaluate students has many flaws, but almost everyone will agree that we need to approximate the highly subjective value of each student as accurately as possible. It’s time to turn this level of institutional evaluation inward to allow for a more meritocratic academia.

While the evaluation of professors described above can and should be completed by peers, there are limitations to the extent to which one’s colleagues can provide unbiased feedback. And when censorship of crucial research is on the line, as was the case under the Bush-Cheney administration, all chances of bias must be removed. Thus, I propose that universities construct a structurally independent group of individuals with a low probability of external influence, i.e., no current or former faculty members and no administrators, to serve as watchdogs for faculty suppression. They could run ongoing audits of funding allocation and the hiring and firing of faculty members, as well as investigate when faculty members raise concerns related to free inquiry.

A natural response to these suggestions for increased faculty obligations, in the case of ongoing evaluations, and the creation of a watchdog group would be: Where will the money for all of this come from? It would take many more columns to get into the details of inflated tuition and the misuse of funding at institutions of higher education. For now, I’ll simply concede that to finance such efforts would require a serious overhaul of the way universities and colleges are budgeted.

Higher education institutions are cautious behemoths wary of making big changes––especially when money is on the line. The movement towards a tenure-free system will almost certainly need to originate elsewhere. But if professors voluntarily revoke their tenure status in support of this shift, they can signal their high valuation of quality and diversity to encourage structural change. UChicago professor Steven Levitt has already advocated for replacing tenure status with an increase in pay, effectively balancing out the job security tenure provides, and offered to make this trade himself. This model could serve as an effective way to incentivize confidently competent professors to compensate for the downsides of sacrificing tenure before the tenure system is dismantled. This would also be an opportunity for UChicago to keep up the airs of its current ethos of innovation in higher education, signaled, for instance, through its early adoption of the test-optional policy.

I’m keenly aware of how idealistic these suggestions are, but if universities are going to keep purporting to aim at the lofty goal of advancing academic fields and educating “citizens and citizen-leaders for our society,” they must be willing to take well-informed risks. We simply cannot expect universities to be bastions for the advancement of human knowledge when our standards for institutional quality are so limited. But if just a handful of bold and motivated professors decide to voluntarily renounce their tenure, we can start to change academia for the better.

Clark Kovacs is a second-year in the College.