It seems safe to say that the news that our return to campus would be pushed back by three weeks was met with a less-than-stellar reception. Many students—myself included—didn’t have enough time to change our travel plans on just over a week’s notice, which stung especially hard given the amount of advance warning provided by other universities. For instance, Harvard announced that they would go online a week before UChicago did, even though their upcoming term was scheduled to start three weeks after our winter quarter began. Even other schools on the quarter system didn’t sweep the rug out from under their students’ feet quite so sharply; Stanford and DePaul announced that their first two weeks would be online while UChicago had still “made no decisions or changes to alter the approach for Winter Quarter.” Our administration was also largely alone in closing the residence halls, which left students’ housing for those three weeks in the uncertain hands of a case-by-case review. But even if it’s a generally held opinion that the University’s handling of winter quarter has been unacceptable, we are beholden to a system of social pressures deterring us from transferring or withdrawing, even if it means enduring administrative failures like this one. The problem is that when we allow the University’s decision-making to escape scrutiny, we give up our only leverage by which to hold it accountable for its actions. And as long as we continue to uphold the aspects of our culture that discourage frustrated students from transferring, our criticisms will always play second fiddle to our devotion to UChicago.

Without a doubt, there’s a stigma attached to leaving college, and UChicago’s academic environment is far from exempt. As is the case with most highly ranked colleges, being here is viewed as a rare opportunity that we’re expected to take full advantage of. Given the chance, there’s little doubt that students across the country would trade places with us in a heartbeat. We’re naturally reluctant to sacrifice this privilege over gripes that seem trivial in comparison; after all, aren’t a few weeks of advance notice on housing plans a small price to pay for the chance to attend the University of Chicago? Giving that up means forgoing the quality of education, the value of a UChicago degree, and the connections we might have made here. And if we still don’t believe that’s worth the drawbacks, people whose opinions we care about often will, encouraging us to stay strong amid whatever challenges may come our way.

That messaging resonates with us largely because we welcome challenges. Many of us are here specifically because we expect to be challenged. No matter how difficult it is to keep pace with the academic demands we’re faced with, we judge ourselves by our ability to overcome situations that push us to our limits. At UChicago, trials like these are to be found around every corner, and we take it upon ourselves to meet them. Having accepted the challenge of making it through the College, we feel compelled to see that goal through; deciding to abandon it feels as though we’re admitting defeat. That pattern isn’t unique to UChicago, either—in fact, our freshman retention rate is around 99 percent, second only to MIT. As another top school with the reputation of being something of a pressure cooker (feel free to look up the acronym “IHTFP” if you’re unfamiliar), MIT similarly dares its students to hold firm through four years of brutal academic rigor.

Going to college is a significant investment in terms of time, money, and effort, and UChicago is especially demanding in these respects. With the combination of the taxing coursework and exorbitant price tag, returning students—especially the 60 percent relying on financial aid—are forced to carefully consider the sunk cost from their time in the College before deciding to withdraw or transfer. The Core also plays a major role here: At universities that don’t share the general education requirements that we fulfill in our first two years at UChicago, transferring could cause us to fall behind our peers in progress toward our majors.

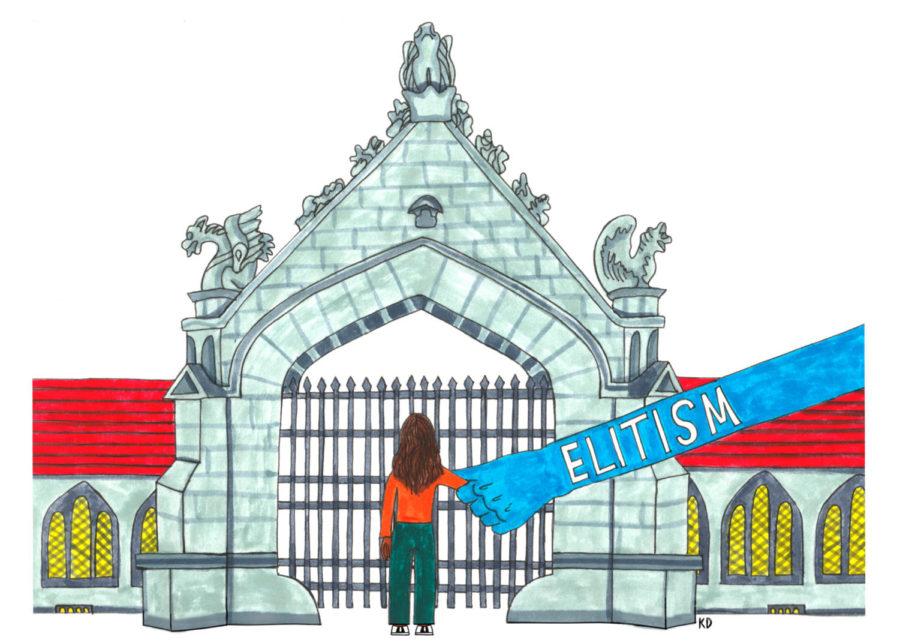

Another contributing factor is that UChicago has deliberately set itself apart from other major research institutions through its trademark emphasis on free expression and individualism. By staking out this position as a unique feature of our shared identity, it has cultivated a sense among us that the assortment of interesting people we engage with on a daily basis can’t be found anywhere else. Even though that’s obviously false—the wealth of fascinating human beings and inimitable ways of thinking in the world could never be constrained to such a narrow bubble as ours—we’re all too happy to subscribe to that image because it boosts our own egos by telling us that we’re special. That, in conjunction with the validation of being admitted to a selective university, is a ripe breeding ground for the elitism of which name-brand universities like ours tend to be accused. Internalizing the belief that our college marks us as exceptional, however, serves as a powerful deterrent from withdrawing; we’re unwilling to forsake UChicago if it means giving up the “elite” status that comes with it.

Of course, it’s not as though students elsewhere are clamoring to drop out in comparison. No matter where you go to college, withdrawing or transferring is always a difficult and involved process, and is enough of a time commitment that few people will attempt it without being sure that they’re dissatisfied where they are. It forces them to uproot the lives that they’ve already built and adjust to a completely new environment, whether academic or professional. Despite these universal concerns, however, the fact remains that UChicago students are particularly averse to leaving—a pattern that begs explanation. It’s also undeniable that our administration is markedly more willing to make unpopular decisions than its peers around the country, such as closing campus on next to no notice, increasing UCPD presence in Hyde Park, shortening the quarter by a week, manipulating our financial aid, refusing to make stronger commitments to sustainability, or not improving a mental health support system that often does more harm than good. Even if not all of these demands enjoy unilateral support from the UChicago community, each one marks an instance where the University has disregarded the concerns of its students without fear of repercussions. In the absence of the economic leverage that typically keeps large organizations in line, the administration is at liberty to act wherever its own interests may lead it, however the rest of us may feel about those actions.

This isn’t to say that we all need to immediately take a leave of absence just to make a statement to the University—indeed, nobody should derail their career paths for the purpose of being petty. What we do need is to recognize that UChicago’s abnormally low transfer rate emerges directly from our collective identity and culture, which is something we absolutely can do something about. By holding the status of being at UChicago in such high regard, every student here contributes to the social pressure deterring us from leaving. The responsibility lies in every one of us to purge our mentality of the notion that there’s something uniquely indispensable about this particular university. Because as long as we continue to idolize “the one and only UChicago experience” well past what it deserves from us, there’s nothing keeping the University from ignoring our voices.

Tejas Narayan is a second-year in the College.