Chapter I

I sing the body electric,/ The armies of those I love engirth me and I engirth them,/ They will not let me off till I go with them, respond to them,/ And discorrupt them, and charge them full with the charge of the soul.

—Walt Whitman, “I Sing the Body Electric”

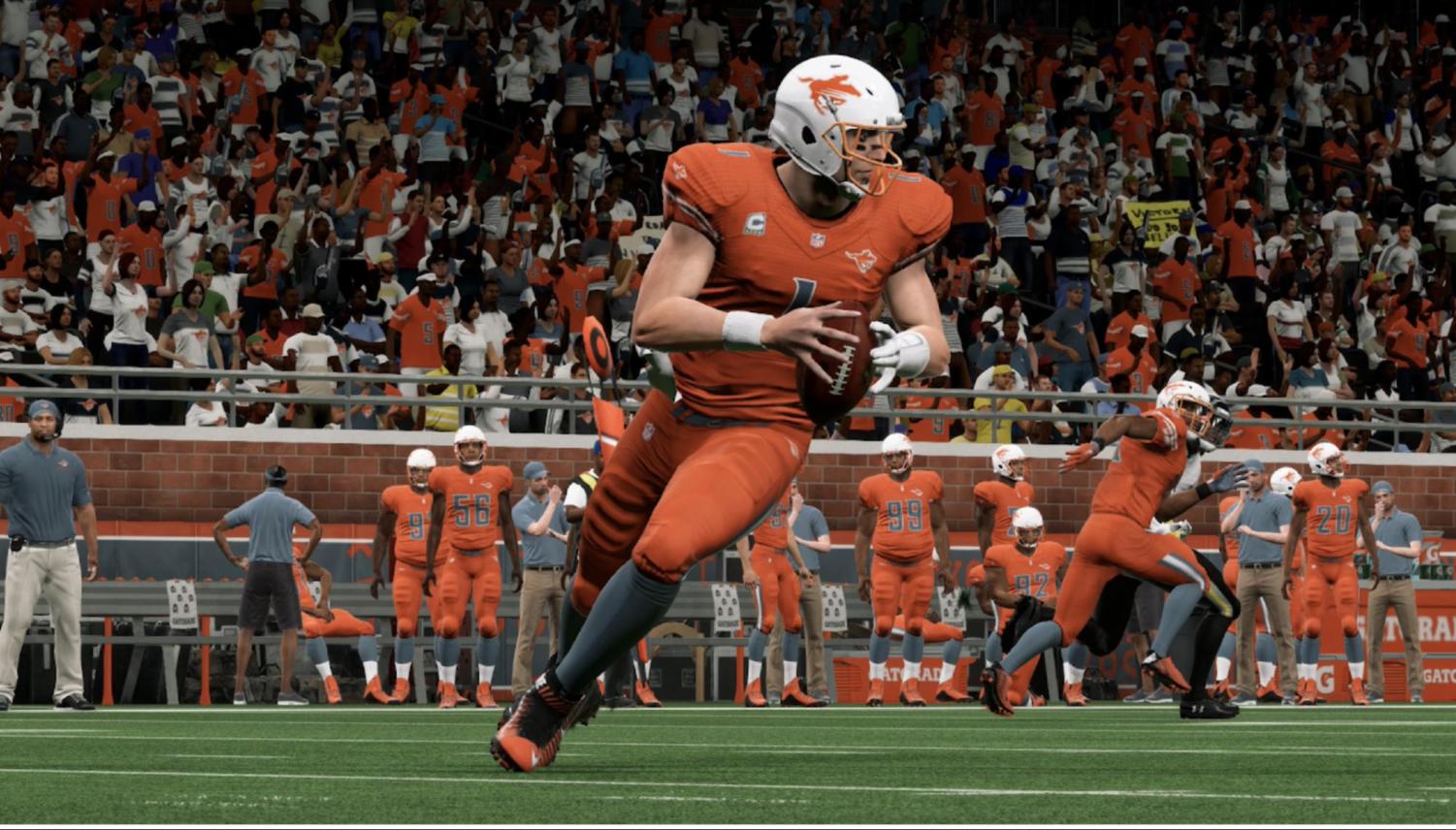

It is immediately apparent to all those who bear witness to the offensive orchestra of the 2028 New York Jets that whatever is transpiring on all 57,600 square feet of turf is closer to the physical embodiment of nirvana itself than anything resembling American football. The players’ movement is artistry a performance almost orchestral in its nature. Jets quarterback Phillip Westbrook lofts a parabolic speck of pigskin to wide receiver Felix Barden, who strides across the field with an effortlessness that thumbs its nose at even the mighty Icarus; he is the master of his body, his destiny, and he flies where he pleases, defensive backs and preconceived notions of the laws of physics be damned. This is techne. The philosophy of making and doing. The philosophy that Sings the Body Electric. The ball lands perfectly in Barden’s hands. Some coaches would refer to this pass as one that is “dropped in the bucket,” but, personally, I detest this term. Its clunkiness divorces the physical movement required to execute the action from the artistry and romanticism inherent in the action itself. The more accurate description would be “right in his breadbasket.” The technical prowess and intentionality of a baker is much more akin to this gesture of giving and receiving than a mere ball being dropped in a bucket with a philistinic, metallic BONK. In this moment, Felix Barden is literally receiving a gift, engaging in techne, actively participating in the creation of art, and, of course, scoring a touchdown. The crowd explodes into a cacophonous expression of awe and mirth. But their cries of passion fall upon deaf ears. This is all an illusion, a simulation, an expression of a highly curated reality that offers a presentation of reality that cannot and will not exist. It’s not real. None of this is real.

The Essence of Our Divine Creator Drops Back for a Hail Mary Approximately 150,000 Years After the Big Bang

Chapter II

“I’m in a complicated relationship with a fictional character.”

—Unknown

Even if you’re not familiar with the concept of parasocial relationships by name, you’re almost certainly familiar with them in principle. In the broadest sense, a parasocial relationship is defined as a one-sided relationship between the consumer of a piece of media and the subject of that media. The relationship is inherently one-sided; the consumer often has lots of information about the minute personal details of the person or character being presented, whereas the person on the receiving end of the relationship has no idea that the observer even exists, let alone what cars they drive or what music they listen to. Celebrity crushes are a common example of parasocial relationships that pretty much everyone has confronted at some point in their lives, as was made evident by my eighth-grade peer group’s wails of disappointment after they discovered that Margot Robbie and Tom Ackerley had tied the knot.

However, parasocial relationships can, and often do, form between observers and people that do not exist. For example, take a moment and recall someone you know saying how much they love and know about Harry Potter (the character, not the franchise). Then consider how much Harry Potter knows about them.

As technology has progressed to the point where previously unfathomable levels of simulated realism are now commonplace, we have begun to build parasocial relationships with even more distant concepts, ideas, and people-adjacent people. We have gone from having parasocial relationships with people to parasocial relationships with characters to parasocial relationships with characters that exist exclusively in universes created and curated for the sole purpose of our entertainment. In these universes, these characters are this strange mix of attributes and archetypes that anyone who is familiar with the more general source material will immediately recognize, but they are scrambled to such an extent that any one character that exists in an individual universe will be a complete stranger to anyone else who might be playing the same game at the same time. What does this mean for entertainment? What does this mean for the NFL? More importantly, what does this mean for us?

Portrait of the Undefined Vanity. What will happen if even our most basic relationships enter a state of perpetual entropic decay in which the people who know you really know you less than everyone else and all of the people who really know you don’t even exist at all?

Chapter III

I met a traveller from an antique land/ Who said—”Two vast and trunkless legs of stone/ Stand in the desert… Near them, on the sand,/ Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown,/ And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,/ Tell that its sculptor well those passions read/ Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,/ The hand that mocked them and the heart that fed;/ And on the pedestal these words appear:/ My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings;/ Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!/ Nothing beside remains. Round the decay/ Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare/ The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

—Percy Bysshe Shelley, “Ozymandias”

At this stage, saying things like, “It is undeniable that the COVID-19 pandemic has altered both our daily lives and relationships with social institutions to such a degree that society will never be the same” approaches levels of adspeak banality that one might describe as vomit-inducing. But the bilious nature of such prose does not make it any less valid, especially when it comes to American football.

Wherever you fall along the spectrum between having preemptive Lombardi trophies tattooed on your preferred bicep and uninterestedly eating store-bought appetizers at an acquaintance’s Super Bowl party, football is an element of the American sociocultural condition that seems to affect the population in ways that go far beyond the field of play. American football is not “in the spirit of the time” as much as it simply is the spirit of the time. As much a social experiment as it is a work of art in both technique and presentation, interspersed with a sort of sadly comical quantity of epilepsy-inducing advertisements and seemingly strange sponsorships, football is at once a violently emotional and an emotionally violent game.

Skrewball Peanut Butter Whiskey, the official whiskey of the Buffalo Bills.

In all of the pomp and circumstance, it can be weirdly easy to forget that the players that our culture loves to deify are actual, living, breathing people. Especially when you’re watching them on television, all you really see are 22 athletes performing feats of strength, speed, and acrobatics, the difficulty of which is quite frankly incomprehensible to the average viewer. No matter how often the armchair athletes of the world might insist that they could totally make that pass, catch, or tackle, odds are that they certainly could not. What’s stranger still is that this disconnect between “player” and “person” persists despite the fact that a lot of these players talk to the media quite a bit. Press conferences, pre- and post-game interviews, podcast episodes, and social media platforms all seek to bridge the gap between the fans’ understanding of these players as physical paragons and the players’ being people with lives and families. However, in the instances in which these players speak to the media for any extended period of time, their answers to the media personnel’s milquetoast questions are often just as interesting as the questions themselves.

Reporter: Mr. Doe, what gave you the confidence to go for that deep pass in the final minute of the game? What did you see on the field that made you feel comfortable taking that risk?

Mr. Doe: First off, man, I just wanna thank God for putting me in this position because without Him, none of this would be possible. But at the end of the day, I’ve just got a lot of trust in my guys and their ability to go out there and make plays, and I know that Coach has been doing his best to put me in positions where he knows I can succeed, and I really appreciate that. As far as that pass, you know, Coach told me to expect them to bring the heat on third down, and I knew if I could hold on for long enough and the big fellas up front could hold the line for a bit, one of my awesome wideouts could get into open space and make a great play. And that’s pretty much what happened, and we got a big gain out of it.

This is the weird catch-22 that plagues interviews like this. As fans, we have a part of us that wants to learn more about the players’ personalities through interviews like these, but it’s a lot harder than you might think for players to talk about their positive attributes in a way that doesn’t sound totally arrogant. Which is precisely why it’s so interesting that so many sports journalists continue to insist upon this style of reporting, knowing that social graces dictate that the player being interviewed should answer the question in a way that credits everyone but themselves. Consider another possible response to the same question:

Reporter: Mr. Doe, what gave you the confidence to go for that deep pass in the final minute of the game? What did you see on the field that made you feel comfortable taking that risk?

Mr. Doe: At the end of the day, I just knew I could put that ball right in the spot it needed to be so the DB [defensive back] couldn’t make a play on it. That throw wasn’t any different from the throws that I’ve been making all season. You can sic all 11 men on me right from the snap, and I know I’ll put that ball right where it needs to be. I’m playing hot right now and it’ll take an act of God for me to not throw for four touchdowns on your top defender’s head. That’s just how I roll.

We go into these interviews with the expectation that they’ll help us, as fans, garner more personal insights about our favorite players, but really they serve as either a showcase of script recitation or a variety bag of idiosyncratic douchebaggery. As a function of this condition, the vast majority of our parasocial relationships with these players are forged and maintained by their actions on the field. How many yards they throw for, how many touchdowns they score, and how they perform under pressure, when they realize that the whole nation will analyze and criticize the motions made over the course of the next four seconds for the rest of their lives. For any New Orleans Saints fans who might be reading this, I feel like I can encapsulate this phenomenon rather succinctly: Marcus Williams, whose whiffed tackle against Stefon Diggs on the final play of the 2017–18 National Football Conference divisional playoff game between the Saints and the Minnesota Vikings, will now be forever remembered as “the poor schmuck who allowed the Minneapolis Miracle” despite otherwise solid play throughout his young career.

Diggs! Sideline! Touchdown! Unbelievable!

Especially with the advent of fantasy football, a fan’s relationship with a player falls on this weird boundary between parasocial and commensalist. If John Smith manages Dalvin Cook in his office fantasy league, John Smith determines the extent to which he maintains a positive relationship with Cook by evaluating Cook’s health and the week-to-week consistency of his fantasy performance. Over the course of the season, John Smith can learn a lot about Cook through an examination of his “numbers”—the statistics that the powers that be have deemed important enough to warrant tracking. One week, Cook might go off, rushing for 200 yards and three touchdowns in an impressive 38-point performance, but the next, Cook might only rush for 17 yards and leave the game in the second quarter with an ankle injury. In John Smith’s mind, he’s been screwed; he may even resort to shouting profanities at this little digitized representation of Cook’s statistics for that particular game. But not only does Dalvin Cook not know that John Smith exists, he is wholly unaffected by John Smith’s annoyance.

As a layperson, I assume that the social makeup of NFL players, with regards to their off-the-field temperament, isn’t too different from the rest of the general population. (Well, in most cases. It’s an unfortunate truth that, despite discipline efforts from the NFL, there has always been a notable minority of players who are serial domestic abusers, aggravated assaulters, and worse.) You’ve also got a few characters who, at least in what they show to the media, appear to be very strange people. But then again, very strange people exist in everyday life as well. I suspect most NFL players are just like you and me, in the sense that they’re decent people trying their best to make a nice living and provide for their families. In this sense, Joe Burrow is quite probably, generational athletic talent notwithstanding, your average Joe.

“If it’s just that we naively expect geniuses-in-motion to be also geniuses-in-reflection, then their failure to be that shouldn’t really seem any crueler or more disillusioning than Kant’s glass jaw or Eliot’s inability to hit the curve.” —David Foster Wallace, “How Tracy Austin Broke My Heart”

This is why we forge our parasocial relationships with these players on the field and through our televisions rather than through their press releases and personal statements. It might seem strange or disconcerting to consider that we are able to form deep emotional attachments to a set of motions that certain players are marginally better at performing than others, but the emphasis on the commodification of motion that is so inherent in the act of engaging in organized professional sport allows for this dynamic to persist without much second thought. Actions are done with the intention of helping “your team” march ever closer to victory, which further emphasizes the true depth of the parasocial rabbit hole. This might be odd to think about from the perspective of a fan, but such a dynamic is no secret to the NFL’s top brass. In a cruel sense that’s reminiscent of Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, football players are not unlike cattle. A player provides value to an organization as long as they continue to meet or exceed the statistical expectations set for them, and, critically in a ultra-physical game like American football, remain healthy enough to do so. You can be the most spectacularly talented player at your position for years, but just one freak injury or slight drop in production can, quite literally, send you packing. Hidden in all of the razzle-dazzle of the bright lights and the pathos-invoking advertisements assuring fans that “This Is Football” or “We Are Football” or something to that effect, there is a brutal but wholly unsurprising economy that governs our most carnal jest. Yet our parasocial connections to these players continue to exist in the form of memories, of their former or potential greatness.

Sometimes it takes a Theismann-level injury (don’t look it up if you don’t know) to make the potential for gore apparent to us. Sometimes it takes watching someone’s nearly getting torn limb from limb on live television for our entertainment for us, the collective, to realize that these aren’t just statistics or blue checks on Twitter or personifications of techne. These are people. When did we lose sight of that?

“There were groups of cattle being driven to the chutes, which were roadways about fifteen feet wide, raised high above the pens. In these chutes the stream of animals was continuous; it was quite uncanny to watch them, pressing on to their fate, all unsuspicious—a very river of death. Our friends were not poetical, and the sight suggested to them no metaphors of human destiny; they thought only of the wonderful efficiency of it all.” —Upton Sinclair, “The Jungle”

Chapter IV

Anyone who is even remotely familiar with the genre of sports video games surely knows—and has regularly condemned the perpetual failures of—the Madden franchise. For those of you who are unaware, Madden is an annual series of, heavy quotes, “simulation football games,” which uses this outward assertion as a vehicle to shamelessly peddle microtransactions. However, almost certainly unintentionally, for the select users who try their best to make Madden a true simulation through the use of its “Franchise” mode, there exists one of the most fascinating modern experiments testing out the potential prototypes for new kinds of parasocial relationships that could define the coming generations.

Each year, more than 250 new players (not including undrafted free agents) join the NFL via the annual draft, in which each team gets a shot at selecting the most promising college players from around the country with the goal of finding the next generational superstar. In real life, NFL teams obviously have no difficulties finding at least 250 college football players who are willing and able to cut it at the NFL level. But in a game like Madden, where one can simulate 20 years in a matter of hours, another solution is necessary. Enter what I like to call the procedurally generated draft class, or PGDC.

PGDCs circumvent this issue by generating unique classes of players each year for the existing teams to draft. Each generated player has their own name, face scan, physical attributes, development potential, and “player tendencies” that can be borderline classified as personality traits. As the simulated years progress and the players that we all know and love begin to succumb to Father Time and inevitably retire, these PGDC products become the new faces of the NFL. But this is just the beginning.

I fear the day when we allow our technology to distance us from our techne, our essence. In this moment, we will cease to be human beings. We will be simply, flatly human.

Chapter V

“The death of the individual is not disconnection but simply withdrawal. The corpse is like a footprint or an echo—the dissolving trance of something which the Self has ceased to do.”

—Alan Watts

We’ve already discussed the banality of COVID-related institutional and commercial prose to an extent sufficient for the scope of this article. But there’s one critical element of this discourse that often falls under the radar, despite the ways that the authors of such prose come so tantalizingly close to unraveling the true depths of complexity. This prolonged period of isolation has created a paradigm in which we, as a society, have been forced to reevaluate the ways in which we view our interpersonal relationships. Sure, the topic of Zoom fatigue has been beaten to death worse than the biannual beatdown of my hometown Jacksonville Jaguars at the hands (and shoulder pads) of King Henry and his court, and I’m certain that we’ve all got our opinions about the correlation between prolonged online classes and that seemingly unshakable sense of ennui that’s got us gripped by the throat. But that’s just the tip of the iceberg.

“Above the gray land and the spasms of bleak dust which drift endlessly over it, you perceive, after a moment, the eyes of Doctor T. J. Eckleburg. The eyes of Doctor T. J. Eckleburg are blue and gigantic—their retinas are one yard high. They look out of no face, but, instead, from a pair of enormous yellow spectacles which pass over a non-existent nose. Evidently some wag of an oculist set them there to fatten his practice in the borough of Queens, and then sank down himself into eternal blindness, or forgot them and moved away.” —F. Scott Fitzgerald, “The Great Gatsby”

Just the other night, I was watching some football with my family when I was confronted with a palpable example of a company attempting to develop an emotional rapport with its customers. The game coverage had temporarily cut to commercial, and the subject of the commercial turned to the camera and said, without a shred of irony, “Applebee’s is who I am.” Beyond the physiological response of literally recoiling in my chair, this commercial made me reconsider the relationships we have with brands and brand entities. More specifically, the ways in which the absence of the immediate access we typically have to the products that have slowly shouldered their way into our identities has highlighted the insecure attachment we have developed to these products. On a surface level, the idea of someone saying that they are Applebee’s seems completely asinine. One can certainly have some degree of emotional attachment to a chain restaurant, but there must be other elements of a deep, emotionally complex person beyond Applebee’s, right? Right?

In an era in our country that seems so predicated upon individualism, is our relationship with the pursuit of individuality so tied to the agents of consumerism that our identities aren’t as much becoming conflated with brand identities as they are brand identities? Even to the extent that our resistance to consumerism has just become another area of consumerism? This might seem like a massive generalization, but I would argue that within the context of evaluating parasocial concepts, such extreme emotional attachments aren’t infeasible. What makes meaningful emotional attachment to Applebee’s any different from meaningful emotional attachment to BTS or Kevin Hart or Mario or, for any other unfortunate souls out there, the Jacksonville Jaguars?

Enter the National Football Association (NFA).

Chapter VI

“Great things are done by a series of small things brought together.”

—Vincent Van Gogh

This is Jared Coffey, starting quarterback for the San Antonio Broncos of the NFA. A former third-round pick out of Georgia Tech, Coffey has carved out an illustrious career for himself, throwing for 4,903 yards and 36 touchdowns to only nine interceptions en route to winning his second MVP award in the 2020 season. But despite all of his regular-season success leading the Broncos to a 13–3 record, Coffey just couldn’t seem to get it done in the playoffs. His team was knocked out in the first round by the New Orleans Talons. At this point, you’re probably wondering what the hell any of this means. I suppose I should explain, but before I can properly continue to catalogue Jared Coffey’s career, let me introduce you to the broader universe of the NFA itself and to the mind of its founder, Jake Willis.

Rather than open with my take on what the NFA is or how you ought to view it, I’ll just give you some content right from the source. After all, he has written more than 125,000 words about this project; I’d consider it disrespectful to begin describing the NFA in a way that deviates from the voice of its creator.

Straight from the official NFA’s “What Is the NFA? Why Should I Care?” page, Willis explains: “The ‘National Football Association’ is the product of 20 seasons of simulation in Madden’s franchise mode. Once the last real player has retired, what’s left to discover is a vast, uncharted sports universe. Through a generation of computer-generated draft classes, Madden will quietly cultivate a league that can be as deep and intricate as the NFL is today… As we played them more often, [the players] gradually turned into harbors of ever-evolving storylines. We watched as all these individual factors… contributed to the successes and failures of the team as a whole, a bigger-picture narrative that was fun to follow as an observer. I was hooked.”

But beyond the origin story of the league, Willis also provides a sort of thesis for the league’s existence as well, further explaining, “In a way, the NFA’s lack of humanity might actually be it’s [sic] selling point. I kind of like how these stories are birthed from a bunch of 1s and 0s. As a sports fan, I’ll sometimes catch myself viewing NFL players as mere means to an end rather than, well, actual people. But in here, there's no harm in pretending as if winning football games is the only thing that makes the world go ’round. These fictional athletes exist in a world with no CTE [chronic traumatic encephalopathy], no racism, no pandemics, no soulless corporations, no politics, no war, no death. Injuries will happen, but only as a plot device. In this fantasy-land league, the players are robots. Their value is determined by what they produce in the game of Madden and nothing else. So the story of the season between the hashmarks is the only thing that matters. Simulation grants us the kind of naivety we often pretend to have when we talk about sports like they’re a matter of life and death. Looking through these teams kind of felt like picking up the NFL as a kid again. I wasn’t a worn out sports fan veteran anymore, one weighed down by toothless talking heads with incessant dead-end arguments, stubborn fans, politics, and the brutality of it all.”

Beyond the sheer dedication that it takes to maintain a project of such unfathomable magnitude, I believe that the NFA’s thesis about the merits of PGDCs and the value of finding stories in data speaks volumes about the future of the individualized corporatist narrative that has been exacerbated by isolation. For the other 99 percent of Madden Franchise players in the known universe, the Jared Coffeys of their worlds would be just that; characters that exist for them, and, to varying extents, because of them. These sorts of hyper-isolated, individualized parasocial relationships have typified the modern era of the social media–driven experience economy. I could walk in to a room of 100 people, and I’m pretty confident that all of them would have some opinion about Spider Man. But your Jared Coffey is, well, yours. The curation of products now has the potential to extend beyond targeted advertisements and handcrafted experiences all the way to handcrafted, curated, hyper-specific relationships with digital entities that seek to mirror the traits and non-traits of your favorite celebrity, football star, actor, writer, friend, enemy, or lover. For the right price, it can be whatever you want it to be. Whoever you want them to be.

And although those latter methods of parasociality may not be available yet, existing simulations, such as these ultra-extended Madden files, certainly serve as a prototype. A prototype for a tool that could, potentially, define my children’s generation. A prototype for a tool that could help provide simulations for the human expression of techne without the, as Henriksen-Willis puts it, “brutality” that has now become so inherently tied to the idea of the creation of physical art. A prototype for a tool that could help us learn more about the minutiae of our day-to-day emotional interactions without any of the normal, potentially gut-wrenching risks. Or the NFA could be the prototype for a tool that furthers the experience economy to the extent that living within its confines becomes so much more appealing than actual interpersonal relationships that we begin to lose touch with one another. Because at the end, of course, we end up losing ourselves.

When the dust finally settled and we got a hang of the intricacies of the World Machine, we noticed a strange pattern. Whenever the interaction got too stressful or the art piece reached levels of physicality that came close to compromising the Orphic Matrices, it activated its final failsafe. It was the coding version of a Hail Mary. The code itself was a sort of fleeting resignation, a final line of defense that it hoped would trigger another one of its little conditionals, something that could give rise to the Youniverse once more. My memory is shaky on some of the technical bits, but the name of the procedure has always stuck with me. It calls back to a game that our ancestors used to play. Techne, I think they called it. The title went like this: When All Else Fails, Launch Deep Spirals Into the Infinite Void. —A computer scientist whose name has long since faded away