And it was Malthus who saw that populations overwhelm their resources without the natural checks of starvation and disease. Malthus was the first one to rub humanity’s nose in the grim facts of unsustainable population growth.

With Urinetown, University Theater (UT) presents a rollicking, campy realization of Hume’s and Malthus’s nightmares. The 1999 musical imagines a world where water is so scarce that private toilets have become infeasible and a single company now owns every toilet in the city—charging its impoverished citizens for every flush.

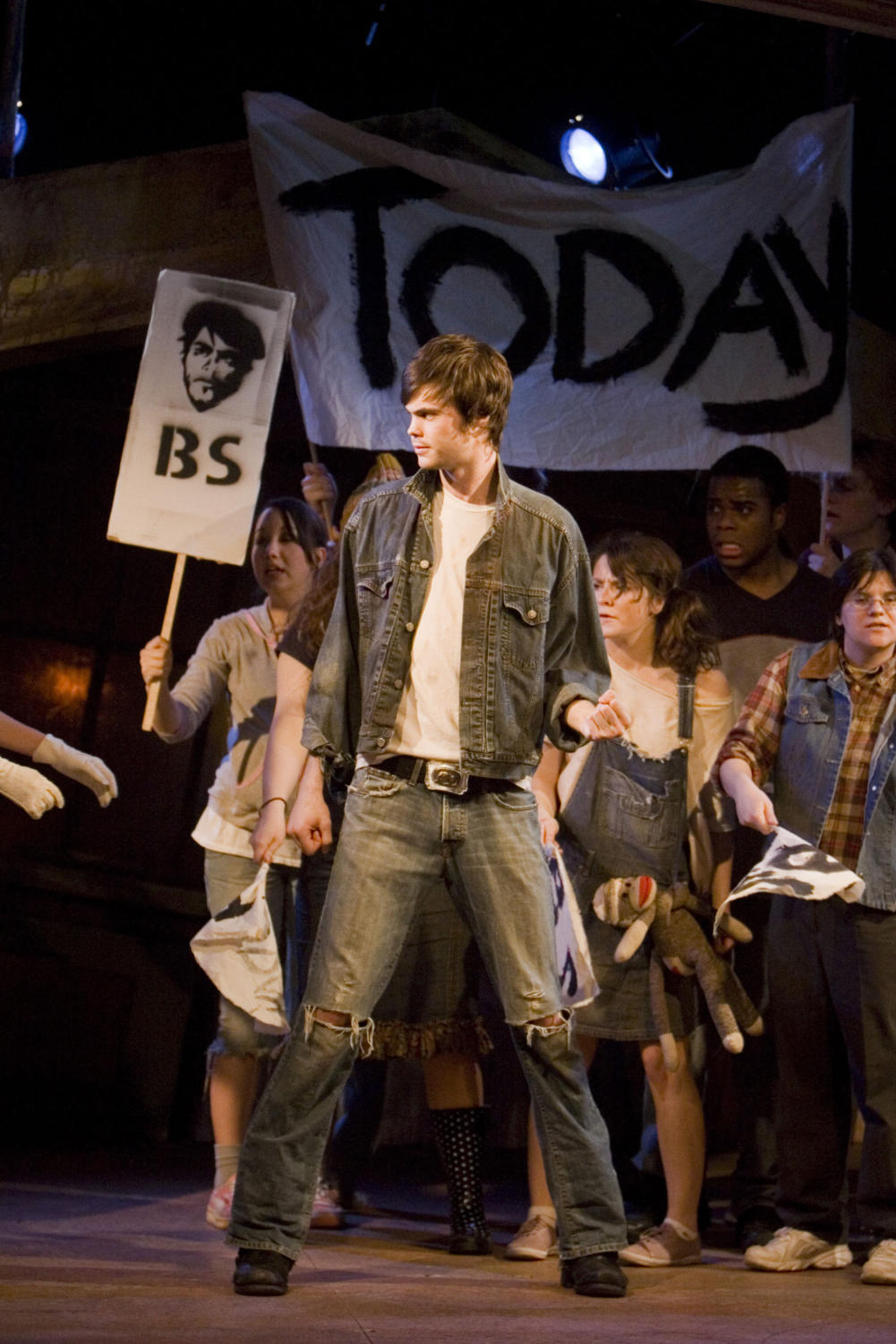

At the center of Urinetown is Bobby Strong, a young man who, like so many young male leads before him, always has his head in the clouds. He works at a public toilet owned by Urine Good Company, the corporation that has monopolized water use in the unnamed city. After his father is “sent to Urinetown” for peeing on the pavement (now a capital crime), Bobby’s conscience is awakened to the evil of Urine Good Company, and he becomes the leader of a rebellion.

Urinetown is a traditional musical with a very unconventional subject. The show has all the usual trappings of Broadway blockbusters: strained metaphors (“love has about as much a chance as a baby bunny drowning in a vat of boiling water”), a lovers’ duet, a big end–of–Act One musical number, an Oliver Twist/Orphan Annie hybrid named Little Sally—you get the idea. Of course, Urinetown is fully aware that it’s aping all of the classic musical theater tropes; there’s a particularly funny scene where Sally and the fourth wall–busting narrator, Officer Lockstock, argue about whether or not the show should be talking about hydraulics.

Little Sally: Say Officer Lockstock, I was thinkin’. We don’t spend much time on hydraulics, do we?

Lockstock: Hydraulics, Little Sally?

Little Sally: You know. Hydraulics. Hydration. Irrigation. Or just plain laundry. Seems to me that all that talk of water shortage and drought and whatnot, we might spend some time on those things, too. After all, a dry spell would affect hydraulics, too, you know.

Lockstock: Why, sure it would, Little Sally. But…how shall I put it? Sometimes—in a musical—it’s better to focus on one big thing rather than a lot of little things. The audience tends to be much happier that way. And it’s easier to write.

Occasionally the play seems to want to have its we-know-it’s-a-silly-musical cake and eat it too. At the heart of Urinetown is a serious point about unsustainable resource consumption, but when it’s couched in jokes that highlight the show’s own artificiality and ham-fistedness, the point gets lost. Still, the play’s brilliant ending, in which the idealism of the rebellion reaps a very barren harvest, certainly doesn’t conform to musical theater conventions.

UT’s production is directed by Jonathan Berry, a Jeffrey Award–nominated director and artistic associate at the Griffin Company, a not-for-profit theater group in Chicago. His seasoned hand can be felt in every aspect of this production, but mostly in the clarity of his blocking and the sustained energy of the performance. Professional music director Allison Kane leads a mixed orchestra of U of C students and professionals through Urinetown’s lively score.

The performances are uniformly good, but a few really stand out. Fourth-year Augie Praley’s Caldwell B. Cladwell, the evil head of Urine Good Company, was a delight to watch. I won’t soon forget his musical numbers “Mr. Cladwell” and “Don’t Be the Bunny;” Praley inhabits the deliciously villainous character with visible joy. First-year Amanda Jacobson’s Little Sally has the proper degree of cloying naïveté. As Officer Lockstock, fourth year Morgan Maher brings a sinister charm to a rather generic character, and his number “Cop Song” was crisply performed. Finally, fourth-year Molly Zeins did an excellent job with Hope, the terminally cheerful daughter of Cladwell.

UT’s production is something of a homecoming for the show. Urinetown can trace its origins to the anarchic improvisational shows of a group called Cardiff Giant, which called Jimmy’s Woodlawn Tap its home in the late 1980s and early ’90s. The group’s founding members, Greg Kotis and Mark Hollman, teamed up once again in 1998 to create Urinetown, which is full of that raucous Chicago improv sensibility. It’s nice to see the show return to its natural habitat after a remarkably successful New York run (the show was nominated for 10 Tonys and picked up three).

Indeed, Urinetown comes to the U of C at exactly the right moment. In these bewildering times, it’s nice to hear someone tell us unequivocally why we’re receiving these cumbersome, expensive educations. To quote Caldwell B. Cladwell, “Did I send you to the Most Expensive University in the World to teach you how to feel conflicted, or to learn how to manipulate great masses of people?” The answer, for him, is clear.