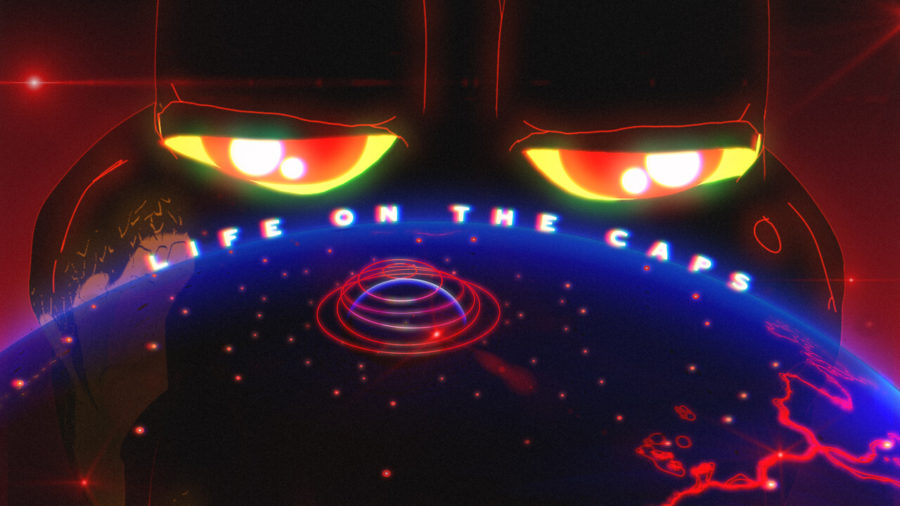

CAPS trilogy:

Party on the CAPS (2018)

2 Lizards (2020)

Life on the CAPS (2022)

In a room filled with students, I sat in the back row of the Gene Siskel Film Center at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) for the screening of two films from Meriem Bennani’s CAPS trilogy: Party on the CAPS (2018) and 2 Lizards (2020), paired with An Evening with Meriem Bennani—a Q&A session with the artist herself. The event was presented in partnership with the Renaissance Society, The University of Chicago’s contemporary art museum.

The first film, Party on the CAPS, and the third film of the trilogy, Life on the CAPS, take place in Bennani’s inventive creation: the CAPS. On the CAPS, a fictional island in the Atlantic Ocean, teleportation has replaced air travel, and displaced populations use a portal to cross oceans and borders. What started as a detention camp for immigrants, imprisoned by American “troopers,” forms into a bustling megalopolis housing descendants of families who “illegally teleported”—as narrated by the gigantic cartoon crocodile. For readers who found the preceding sentence hard to fathom, be warned for an even more surreal experience while watching Bennani’s film.

The second film of the trilogy, 2 Lizards, is Meriem Bennani and Orian Barki’s collaborative film. Originally intended to be an interlude, 2 Lizards chronicles the early days of the pandemic as it unfolds in real-time. During the height of the pandemic, in March 2020, Bennani felt the urge to make a film. Meriem Bennani and Orian Barki spent lockdown together in their Brooklyn apartments, so the lizards in the films represent their conception of the pandemic in real time. Bennani and Barki reflected on their observations and feelings each day and put these details into a short story about their experiences. Bennani used a file of 3-D animal models she had bought for a different project and chose two lizards for their avatars. The similarly animal supporting cast, voiced by their various friends and comprising a hummingbird, a cheetah, a mouse, a cat, and a raccoon, did not stop the audience from empathizing with the anguish felt in each character. Who would've thought that watching Anthony Fauci as an animated snake was what it would take to finally give me closure to the general disorder of March 2020? March 2020 was an Orwellian nightmare, truly leading me to believe the world had come to an end. Now, two years later, I can attend class in-person and walk through the main quad to see people having a picnic or tossing a frisbee to one another.

Although 2 Lizards is not currently being exhibited, the full version is available on Orian Barki’s page, and snippets can be found on Meriem Bennani’s Instagram (@meriembennani). The film is segmented into one- to two-minute episodes.

The experience at the Gene Siskel Film Center was not only aesthetically unique but thought-provoking from a political and existential scope. The movement between the 3-D animation and documentary footage immerses the audience so effectively that there were moments when I felt teleported to the setting of the film. Between animation and documentary, the film fluidly moves from the imaginary to the geopolitical, delving into ideas about global surveillance and the power of the collective, all the while placing an emphasis on emotion. During the Q&A session, Bennani explained how in her world, music is part of world-building; she sources Moroccan and Algerian music for her films, creating not only a visual but also a sonic way to experience her work. Bennani’s masterful layering of animation, documentative film, and North African beats was one of the most wild cinematic sequences I have ever witnessed.

How does one even come up with a film series with a crocodile narrator swimming in electric-wired film water near a fictional island in the Atlantic populated by detained migrants? At the event, Bennani spoke about the fantasia sequence in the film: “The fantasia sequence came from different places as I built the world. The CAPS world is original yet based on personal research around transportation.” Bennani has always been interested in teleportation as a real concept. She questions how countries such as the United States would react to teleportation and how immigration policies would shift as a result. This curiosity surrounding biopolitics and teleportation is highly evident in her creation of the CAPS world.

At the event, Bennani also revealed that the idea of the crocodile as the crest and embodiment of the CAPS was inspired by her time in Morocco. While in Morocco, Bennani noticed a lot of people wearing the clothing brand Lacoste S.A., which displays an iconic crocodile as their logo. After observing this crocodile logo everywhere, she began creating a narrative around the urban legend of crocodiles and drew a map of an island surrounded by a swamp of crocodiles. These threads of thought and observation led to the making of the CAPS.

At one point a SAIC member in the audience asked, “How did you come up with the idea of the United States as a megalomaniac capitalist state?”

“I can’t take credit for that idea,” said Bennani, which the audience responded to with laughter—a realization manifested by humor.

The humorous absurdity encapsulated in reality is part of what Bennani depicts in her work. In the phantasm of it all, the truth of our world becomes realized. The humorous deliverance of Bennani’s dystopian work was one of the most eye-opening things I have experienced. Day-to-day, laughter is what relieves pain, and for me, laughter is what got me through the dark days of the pandemic—watching Bennani’s film brought solace and perspective to the darkness of our world.

Bennani believes her work acts similarly to a documentary but with a different concept: documentary as a creative form. If one really ponders it, a lot of documentaries undergo editing to build a certain narrative, shaping it to be manufactured and contrived. In this sense, Bennani’s world of talking animated lizards conveys more truth than the average documentary. All documentaries have some kind of lens or angle as a filter, and instead of failing to acknowledge the existence of the filter, Bennani embraces and challenges it in the most creatively nuanced way possible.

At the end of the evening, I left the Gene Siskel Film Center at the SAIC feeling unexpectedly satiated. Since the pandemic hit, museums and exhibitions have had limited hours or closures, and it was only after Bennani’s screening that I came to realize how long it has been since I’ve experienced art in a room filled with people. The collective experience of watching this film, Bennani’s magnificence in capturing individual experiences, and her collage assemblage of humorous animations took an unbearable weight off my soul.