How do you begin to dissect a movie that’s literally titled Everything Everywhere All at Once? It defies explanation, defies being broken down or classified into any one thing—it’s a comedy, it’s a martial arts action flick done in the style of Stephen Chow, it’s a hopeless love story, it’s a Wong Kar Wai homage, it’s a family drama, it’s a story about queer pride—it’s Everything you could think of, with film references and whiplashing emotions Everywhere, given unabashedly to the audience All at Once.

I’m reluctant to reduce a film of this scope and magnitude to something so simple as a love letter—Everything Everywhere All at Once feels more like a million shouts of love into an implausible void. But the story at its core is exactly that. It’s a mother pulling together her family, tackling generational and cultural differences to do so (while also learning the encompassing totality of love in the face of the insidious lure of nihilism). Michelle Yeoh stars (and absolutely shines) as Evelyn, a tired laundromat owner who must navigate the skills and emotions of her multiverse selves to save the universe, her family, and her taxes. Along for the ride: Evelyn’s husband, the loving and gentle Waymond (Ke Huy Quan, whose surprising versatility—jumping between martial arts expert, clueless dad, and hopeless romantic—ends up forming a large part of the film’s emotional core); her daughter, the defiantly lost Joy (Stephanie Hsu); and her father, the perpetually cranky Gong Gong (James Hong).

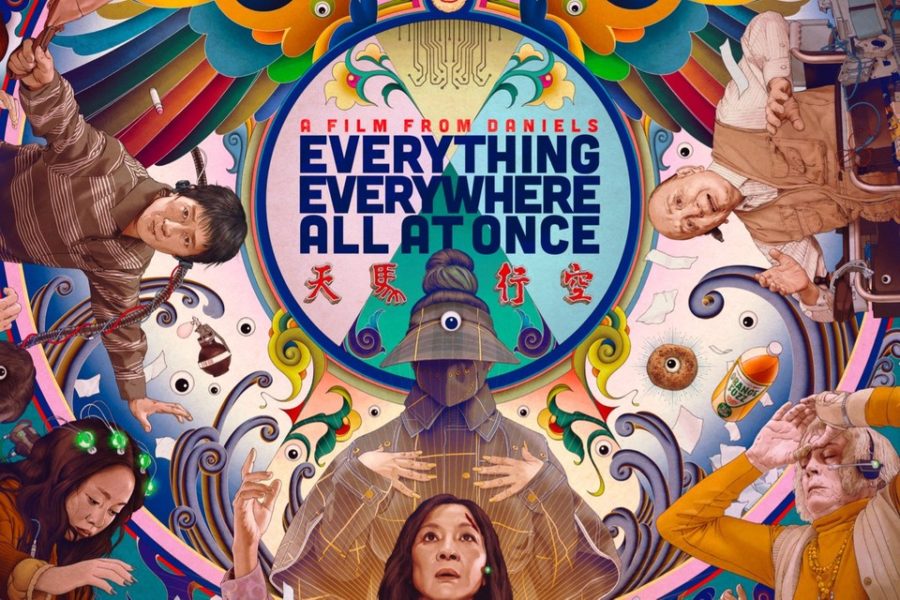

Directed and written by Dan Kwan and Daniel Scheinert, collectively known as Daniels, the film uses absurdity to mask its deeply moving and heartfelt messages. As the duo’s sophomore film outing, following 2016’s Swiss Army Man starring Daniel Radcliffe as a farting corpse, Everything Everywhere All at Once contains all the zany chaos and physical comedy expected from two millennials who cut their directing teeth on music videos like “Turn Down for What.” You’re laughing one second, then suddenly you’re crying, but you’re also still laughing, because onscreen, Harry Shum Jr. is crying over a raccoon and everything suddenly makes sense. And nothing makes sense. Still with me?

The traditional idea of The Chosen One (think Harry Potter from Harry Potter, Neo from The Matrix, Aang from Avatar: The Last Airbender) is that they possess certain special qualities and powers such that only they can save the world. Everything Everywhere All at Once takes the opposite approach, having Laundromat Evelyn be the least successful Evelyn in all the multiverses; she is The Chosen One precisely because she has none of the qualities of The One. Rather than use the idea of the multiverse as fanservice or a cheap gimmick, this allows the Daniels to use the multiverse’s possibilities to set up Evelyn’s character conceit: to save the world, Evelyn must tap into the potential displayed by her multiverse selves while also accepting the choices, sacrifices, and resulting dissatisfaction of her own universe.

Of course, this conceit would be nothing without Yeoh’s masterful performance. Evelyn is a role that was written for Yeoh, showcasing Yeoh’s accustomed elegance and martial arts wizardry (echoing earlier roles in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, or more recently, Crazy Rich Asians and Shang-Chi). But there’s also vulnerability, butt-plug fight scenes, romantic waltzing with hot dog fingers, and so many other emotional depths that Yeoh plumbs and displays. You keep wondering how Hollywood has never had Yeoh in a headlining role before now (answer: racism), and why no one else has ever made an Asian immigrant mother the star of a Chosen One story (answer: also racism).

Everything Everywhere All at Once is not an Immigrant Story. But its expression of common immigrant stories and conflicts is unexpectedly heartfelt and authentic. There’s the trilingual switching between English, Mandarin, and Cantonese—sometimes mid-sentence—to signal generational disconnect. Evelyn’s crabby misremembering of Ratatouille as “Raccaccoonie” which becomes the film’s best running gag. And ultimately, the generational conflict of parental pressure and obligations: Gong Gong never fully accepts Evelyn, while Evelyn continues to take care of him in his old age. And a generation later, Evelyn initially refuses to fully accept Joy because of the latter’s queer identity, which mimics the casual homophobia of many an immigrant parent who are “fine” with their kids dating the same gender, but like. Not really fine.

All of this is wrapped up in a non-stop bombastic tour of the multiverse. The multiverse, as a concept, is at its best when it’s purposely unhinged—something Daniels know how to lean into. Although the worldbuilding and exposition gets heavy, leaving less time for certain character resolutions (Gong Gong’s sudden acceptance of Joy’s girlfriend Becky (Tallie Medel) is a little ham-fisted), there’s enough action and comedy that the exploration never feels slow. In the end, Everything Everywhere All at Once urges us to be kind. Even as we hurtle through the multiverse, even as we are surrounded by chaos and nihilism—be kind.

I’d be remiss in this review if I did not mention my own Asian immigrant mother, who has provided critical reactions and lines for some of my other The Chicago Maroon reviews. There were so many moments in Everything Everywhere All at Once where I thought, that’s exactly what my mom would do here. That’s definitely something she would say—wait, my mom would make a great (and hilarious) multiverse hero. So, this review is for my mom, who will not understand why she would be the best multiverse hero and lightheartedly complain about it anyway.

(When I told my mom why Evelyn reminded me of her, she brusquely dismissed the comparison to ask whether Everything Everywhere All at Once is a good movie. Is it worth seeing in theaters? Yes, Mom. It is.)