At the Night Owls event on November 3, a self-described “moral philosophy major for undergrad and now grad school econ student” asked the first question to the guest lecturer Leon Wieseltier. His confession, with its weighty pause between the “and now,” amused aspiring intellectuals in the audience. His caveat “not the evil type” didn’t do much to quash giggles.

On campus, econ majors get bullied a fair amount. A winter quarter Theater[24] troupe recently put a comedic spin on Hamlet where, of course, he becomes a major in the aforementioned field and changes his name to Chad. Forced to seek refuge from snarky humanities and STEM people, econ majors stick to their business frats and consulting clubs. I’m prompting exploration of the Booth School, though, not just for econ students on the run. I know it might be truly hard for you film bros, art hoes, Marxists, and (pure) mathematicians to consider my proposal. But, hey, I’m not an academic advisor selling econ electives to third-year major-switchers out for more “useful” courses; I’m steering you, if you will, to see art.

Booth has a serious contemporary collection; there’s art everywhere. On every floor, in all the hallways, even in the stairwells, there’s photography, painting, collage, drawing, sculpture, digital art, and interactive multimedia installations. The curation bends toward internationalism—it’s even a little disorienting moving from Hyung S. Kim’s photography project on a Korean community of free-diving women fishers to Seydou Keita’s graceful portraits of Bamako citizens to Andrei Tarkovsky’s Italian vacation polaroids (Booth’s set of quiet and pretty Tarkovsky pictures, more than Letterboxd ravings, might be what convinces me to finally go for Stalker or Andrei Rublev).

Looking at art in Booth is odd, because of both the place’s visual clutter and its working students and staff. Promotional posters with portraits of Booth faculty members get mixed up with artwork on the walls. Labels for pieces on eye level with branded classrooms cause momentary confusion…is “Credit Suisse classroom” the title of an ironic piece? Wolfgang Tillmans’s photos compete for attention with bulletin board fliers and neoliberal memes, like a “deep-fried” Milton Friedman (i.e. oversaturated image). In class or office hours, most Boothies seem too busy to acknowledge the works around them. Their discussion of analysis models and polite networking in various languages (small talk is recognizable in any tongue) serve as an odd soundtrack for an art tour. There is little in the way of curatorial assistance. Some pieces have blurbs on their placards or QR codes (when they work) linking to audio clips with a pleasant-on-the-ear, Irish-sounding guide. Fans of the Smart’s headache inducing, size-eight font descriptions will be disappointed.

If Boothies seem to be passing on deep reflection with their collection, perhaps the art has a passive effect—it might be working on Boothies as it’s lived around. For visitors, Booth offers an opportunity to approach art more casually. Away from museum norms of art viewing, you’re freed up, allowing for little epiphanies that sneak up on you. Exploring the place is simply fun. You’re often one-on-one with art, which may be a kind of business-class luxury…guilt me later. I’d like to share a couple works that have stuck with me. Maybe my favorites will spur you to find your own at Booth.

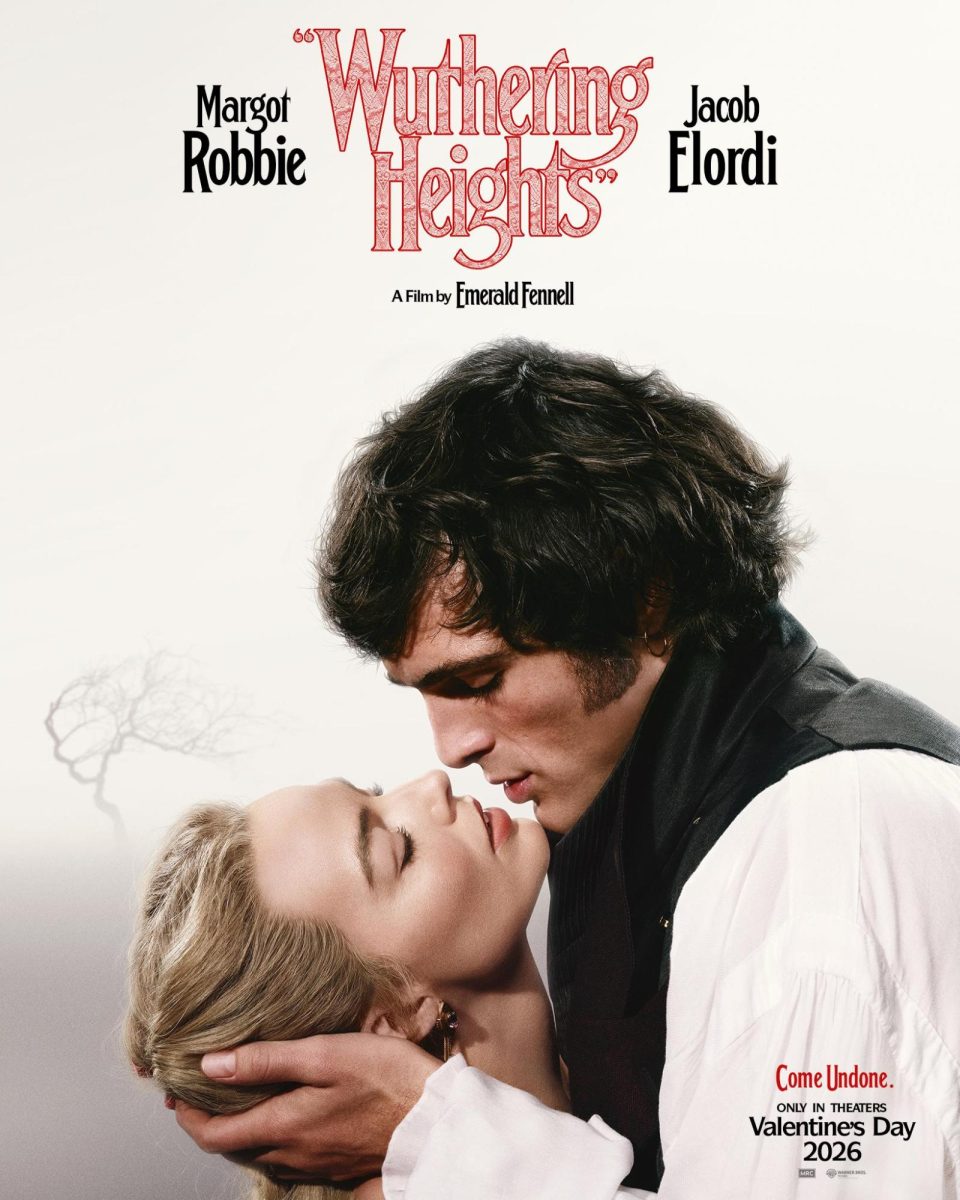

A forest’s ghostly prettiness first drew me to Ori Gersht’s White Noise 01 and White Noise 02. I thought they were paintings in the blurred, realist style of some Gerhard Richter pieces. I’d find out Gersht’s images were photographs he took on a train journey between Auschwitz and Belzec. With context, it occurred to me that this fleeting, hazy scene would have come close to the last glimpses of unbounded natural world seen by those on their way to Nazi concentration camps. In White Noise 02, a big snow–white house in the distance, with closed doors and no homey lights in windows, evoked the apathy of Holocaust bystanders. Only the trees don’t shirk away. The artist wrote on his website: “At all times I was aware of the photographic impossibility of the subject; how could I possibly describe the indescribable, or, as Theodor Adorno once questioned, how can anyone write poetry after Auschwitz?” Gersht does not end up “describing.” He gives us little guidance. It’s on us to take the train: eyes open, never looking away, even if it’s all a blur.

At first, Eduardo Consuegra’s 85%, 90%, and 98% seem like monochrome black squares. You have to get up close to realize the titles refer to ratios of similarity between two shades of black in each painting. Consuegra bought black paints from the same store on different days and compared them.

The paintings got me thinking about Blackness in America: the experience of looking and seeing only the monochrome seemed akin to the way Black people’s particular identities—as stars or as slaves—have often been elided. The various categorizations of color (from “light-skin” memes to Childish Gambino’s “Redbone”) Black people highlight seemed parallel to the way Consuegra, as a painter, attends to differences between shades. Consuegra is Colombian, and there is no curatorial or artist statement about his work in relation to race in America. My notion about Consuegra’s paintings might be off the mark, yet my encounter with his work is probably similar to most people’s: from initial dismissal—boring black—into delightful playing in the dark(s).

The piece I’ll leave off with might be one of the first you’d see at Booth. Mark Grotjahn gambled the commission Booth paid him and recounted his sprees in five drawings. Each pieces’ differing pairs of jutting rays add an aesthetic touch to straightforward summaries. We get extra detail—information about the particular card game and site of play—in the only instance of winnings. Was Grotjahn reflecting on (or, perhaps, in the throes of) momentary success’s blinding power?

Grotjahn’s work reminds us there’s a lot of money behind the collection. Apart from dates and time spent, there’s no way to make Grotjahn’s gambling results real. His pot isn’t an addict’s wages or a sly player’s carefully organized funds. Grotjahn’s play money comes from a private institution’s luxuries fund. His cavalier spending and Booth’s indulgence—unsurprising in the world of art and cash—is detached from the budgeted, careful lives of everyday people. The placement of Grotjahn’s work might be an expression of self-awareness from Booth, an acknowledgement of the art market’s insanities. But this unnamed series could be turned the other way. For Booth’s curators, the pieces—nothing but balance sheets, raw green and chance—might be perfect business.

I’ve had a ball at Booth, and I’m sure most people would find something to connect with in the collection. A hearty endorsement, though, is iffy after a run-in with Grotjahn’s work. Booth isn’t exclusory, but it’s not perfectly inclusive either. Per UChicago Arts, photographer Wolfgang Tillmans “appreciated the fact that the works purchased for the school would be displayed in well-trafficked public spaces, rather than sequestered in storage—frequently the fate of art purchased by private collectors.” But is Booth really a public space? I only nosed around Booth because one of my art history professors told my class to check it out. Since I’ve started going, I’ve come across warm smiles and confused looks (though never any animus). I remember one particularly kind professor, John R. Birge, who told me about his favorite wacky pieces involving “art furniture” (no, not decor), simulated baseball commentary, and intensely lifelike yarn people wearing Vans. To give him a chance to talk up his affections, I pretended I didn’t know these works—I didn’t want to harsh his mellow response to the idea that a non-Boothie was enjoying the art.

When it comes to outreach, I haven’t seen posters urging University undergrads to come see the collection, or public invitations aimed at Southsiders. The building is closed on weekends, when most would have time for art. I hope someone in Booth’s administration grasps the distinction between Merleau-Ponty’s humanism of comprehension and humanism in extension—art appreciation is its own justification, but educational institutions (and teachers) should be committed to democratizing aesthetic experience (All they really need to do on this score is pick up on Birge’s spirit). In the meantime, I urge you, reader, to stretch yourself. Step up to the Booth; everyone should take a shot.

Editor’s note: This article was temporarily removed on the morning of Wednesday, February 22, after issues were found with two sentences. The language of these passages has been adjusted. A sentence containing inaccuracies about linguistics was also removed. The article was reinstated on the evening of February 27.

Editor’s note: The above editor’s note was adjusted on May 9.

![A forest’s ghostly prettiness first drew me to Ori Gersht’s “White Noise 01” [pictured above] and “White Noise 02.”](https://chicagomaroon.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/be7fa2e6-3c36-4b79-952c-bb412abdbb25.png)