In Chapter 720 of the Illinois Compiled Statutes, which contains the Illinois Criminal Code, the reader finds Section 12C-50 on hazing. Under Illinois state law, hazing is classified as a Class A misdemeanor, punishable by up to 364 days in jail and a fine of up to $2,500. The practice is defined as “knowingly requir[ing] the performance of any act by a student or other person in… [an] educational institution of this State, for the purpose of induction or admission into any group… associated or connected with that institution.”

Of course, the University has its own policy on hazing, too: “A person commits hazing when they knowingly require a student or other person at the University to perform any act, on or off University property, for the purpose of induction, admission, or membership into any group, team, organization, or society associated with or connected to the University if the act is not sanctioned or authorized by the University and results in harm to any person or could reasonably be foreseen to result in such harm..… Any student or group that commits hazing will be subject to the germane Student Disciplinary System, as appropriate.”

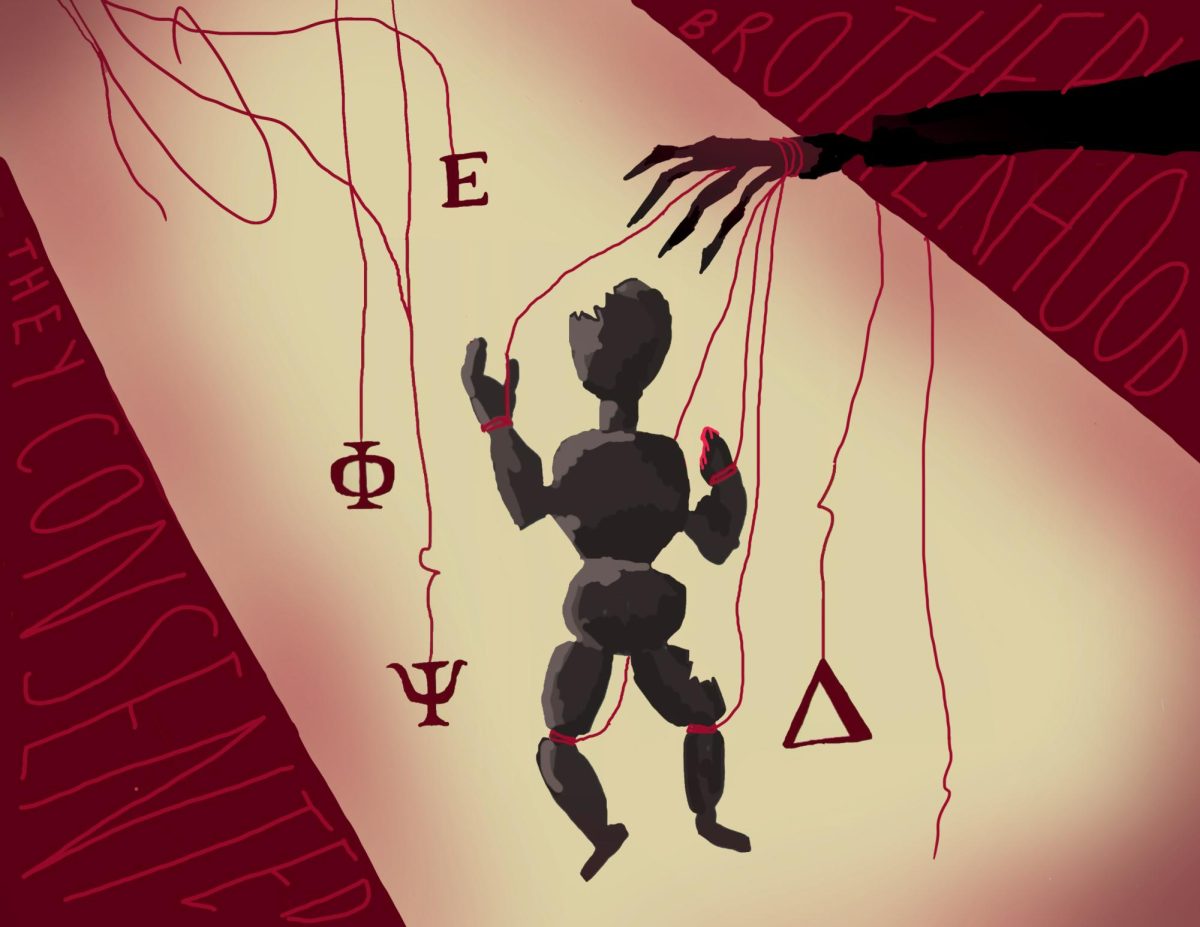

Most UChicago students have encountered hazing in one way or another. You see a stumbling first-year in the lobby of Woodlawn Residential Commons, and someone asks him, “What frat did this to you?” (Look past him and there’s the entryway television displaying a summary of the University policy: “Hazing is illegal under Illinois state law and prohibited by University policy”). Your boyfriend goes dark for hours and reappears with a cagey text saying that he is “just fine, had to line up in the basement again”. Your friends giggle at a Pokémon-clad, condom-carrying pledge in the middle of Bartlett Dining Commons, and you are reminded of the rumor that they aren’t allowed to wash the onesie. A guy who lives down the hall has been carrying a push broom everywhere he goes for the past five weeks. This is how outsiders get an easy glance at some of the more blatant hazing practices that take place quarterly on our very own campus. This is, of course, by design; the layman’s viewership is manufactured to embarrass and emasculate the objects of hazing. It does not matter which costume he wears or what is strung around his neck or burned into his thigh. What all of these practices have in common is that they signify control, domination, and a constant monitoring of personal agency.

Participants in fraternity hazing say that since members of a pledge class always consent to their treatment, they also agree to endure what harm might come from being hazed. It’s a convincing argument. They can walk away when they’d like to, in most cases. But the theoretical freedom to drop out of the process does not translate to actionable agency. There’s an all-in attitude: total commitment to the initiation process is a means to earn a level-up in the fraternity hierarchy. The frequent refrain is that hazing forms bonds, brotherhood, and trust among peers, and that this result is worth sacrificing one’s authority over himself for a short time. Hazing, up to a certain point, seems defensible to most observers as long as the subjects have agreed to it. That is, the use of coercive control is acceptable if the participant has elected to be included.

The law does not agree: “It is not a defense… that the person against whom the hazing was directed consented to or acquiesced in the hazing.” University policy also specifies that “a person’s willingness to participate in an act of hazing does not justify or excuse the act.” The rule books make a good point here. Subjection to social control damages an individual’s relationship to their personal agency. Allowing oneself to experience subjugation does not negate its psychological effects. It might, in fact, worsen them.

While embarrassing costumes and public displays of humiliation may seem trivial, these instances serve to isolate and display what hazing is really about: power and control. A command to wear a particular embarrassing outfit or to sit in an elevator and pretend to defecate in the corner is not really about the outfit or the display, but the command itself. Hazing gratifies the hazer’s desire to have authority over others and to decide who deserves to become his fraternity peer. There is a sadistic nature intrinsic to the actions of the pledge master. Usually a more senior member of the fraternity, the pledge master has been through it all before. He has endured the embarrassment, completed his tasks, reached the end of “hell week,” and he ensures that the next group of hopeful pledges get it just as bad as he and his friends once did. By extension, he aims to ensure that his pledges have earned their place in the brotherhood just as rightfully as he did. From his perspective, it is a matter of the organization being worth the trouble. It is a matter of gaining something greater than what is given up. We can imagine the feeling of honor the pledge master possesses, and we can look at hazing as an elaborate way to cement and actualize the inclusion of new members. It creates borders that must be crossed, signifying the sovereignty and realness of the group itself. Those who complete the process gain power through completion, a self-reinforcing power which exists only through the ritual’s continual perpetuation.

Put simply, it is a cyclical practice, and one in which everyone is made complicit. The entire membership is encouraged to participate and take advantage of the control which is exercised on each new group of young men. Sometimes, this means summoning a pledge to drop everything and bring you a lighter outside of the library. Sometimes it means watching them choke down a smoothie of each other’s vomit when they can’t hold their liquor, or listening through the basement door until someone breaks a bone and earns their escape.

Technically, these instances are legends, and they’re kept that way for a reason. Somewhere along the way, the playful antics of undergraduate camaraderie become prosecutable criminal action. Everyone is involved, so everyone keeps quiet, for the most part. (This exact complicity logic surely reminds the reader of the ways in which sexual assault allegations are swept under the rug. Experts call it the “male peer support theory”). Still, stories of certain rituals have secured themselves as part of the College’s cultural and gossip canon. One particularly infamous example at UChicago which toes the line between playful and abusive is the walk back from Northwestern University. I heard of it my very first week on campus. The pledges are dropped off in Evanston in suits and ties, without money, food, or cellphones, and must make it back to campus on foot, often at night or in the cold. Another common practice, of which the nationwide cases have been more reliably reported on, is the elephant walk. Usually while inebriated, each pledge holds onto the genitalia of the man behind him while inserting his thumb into the anus of the man in front of him. There are many variations on this practice, some of which include extra punishments for the first pledge to let go or leave the line. Coercive control and sexual violence are inextricably linked. I need not illustrate this point further. Hazing, no matter the severity, is a practice of physical, social, and psychological violation. It’s about “taking it.”

The definition of hazing under state law specifies that the act must result in “bodily harm to any person” to be prosecutable under Section 12C-50. University policy broadens this to state that a person commits hazing when the act “results in harm to any person or could reasonably be foreseen to result in such harm.” The reader surely recognizes that wearing a dirty costume and plastic fanny pack does not strictly qualify as hazing under state law and University definitions. Excessive drinking, forced sexual contact, broken bones, and induced exhaustion, however, definitely count.

I contend that we should expand our understanding of harm to include the damage resulting from consistent indifference toward consent-driven attitudes, instead of drawing the line once the crime has occurred. The normalization of social coercive control ought to be treated as a precursor to real injury. This type of harm is not only a danger to consenting fraternity hopefuls, but to the members of the University community whose physical and sexual assault experiences are often treated as an entirely separate issue. In reality, the sexual assault crisis on college campuses nationwide feeds off and prerequires the minimization of consent-driven attitudes. Fraternity hazing is just one common practice which contributes to the devaluation of consent.

Repeated studies over the past two decades have shown that men in fraternities are three times more likely to commit rape than men not in fraternities. John Foubert (who has contributed to much of the relevant literature, and served as the highly qualified expert for sexual assault prevention for the U.S. Army for five years), in a 2013 article for CNN, explains that men in fraternities are more likely to commit sexually violent acts. Gaps in the literature obscure the facts of direct causality, but Foubert and other experts highlight the well-supported possibility that it is the fraternity experience specifically that leads men to be more likely to commit rape. The hazing process is undoubtedly a key tenet of this experience.

In 2019, the University of Chicago joined 32 other universities in completing the Campus Climate Survey on Sexual Assault and Misconduct, conducted by the Association of American Universities (AAU). The AAU aggregate report of all participating schools showed that nationwide, 25.9 percent of undergraduate women had experienced at least one instance of nonconsensual sexual contact since entering university. At the University of Chicago, the proportion of undergraduate women with the same type of experience was 30 percent. If the University ran the survey again, I would join this group myself. The results of the survey also state that fraternity houses were the second-most frequently reported location for instances of rape at UChicago. It is evident that fraternity hazing, with its deep-seated roots in coercive control and violation of consent, poses a serious threat to the well-being of our community. Educational institutions have the responsibility to protect their students. The University of Chicago community must ask if we find ourselves protected.

Sophia Zeglis is a second-year in the College.