The University of Chicago Crime Lab held a webinar to present the findings of its study on Situational Decision-Making (Sit-D) police training on October 3. The aim of the study was to understand the impacts of the new Sit-D style of training, and it found that officers trained in Sit-D reduced both the amount of force used and the number of discretionary arrests made.

The event, moderated by the Crime Lab’s Director of Outreach and Engagement Ken Corey, featured the principal investigator of the study, Oeindrila Dube.

“[Sit-D] was designed carefully with the intent to change how officers approach policing situations that are often high-risk, rapidly unfolding, and ambiguous. For the first time, training was paired with a data-driven evaluation process so we could see just what kind of impact [the training] had,” Corey said.

Dube provided an overview of both how Situational Decision-Making works and how the effects of this training were evaluated.

“[Policing] is cognitively demanding,” Dube said. “Officers need to take in lots of information, consider many possible interpretations, all in situations that are really stressful and require them to act quickly. What decades of psychology research tells us is that it’s exactly in these circumstances under which deliberate reasoning tends to shut down and people instead start resorting to automatic thinking—doing things like using mental shortcuts, making assumptions to reach conclusions instead.”

Dube added that everyone engages in automatic thinking but cautioned against having officers rely on this type of reasoning. “If officers aren’t prepared to meet [the] cognitive demands [of stressful situations], this could have implications for both their safety and the safety of community members.”

Sit-D trains officers to quickly consider the potential contexts of the situation they face through four leading principles. First, Sit-D teaches officers to understand their triggers, the factors that can cause them to not think rationally. Second, officers are instructed to employ self-regulation techniques, such as breathing techniques that control physiological stress, that will enable them to think more carefully. Third, Sit-D encourages officers to recognize “thinking traps” that operate similarly to cognitive biases that can cloud rational judgment. Fourth, officers are taught to think of alternative interpretations of events.

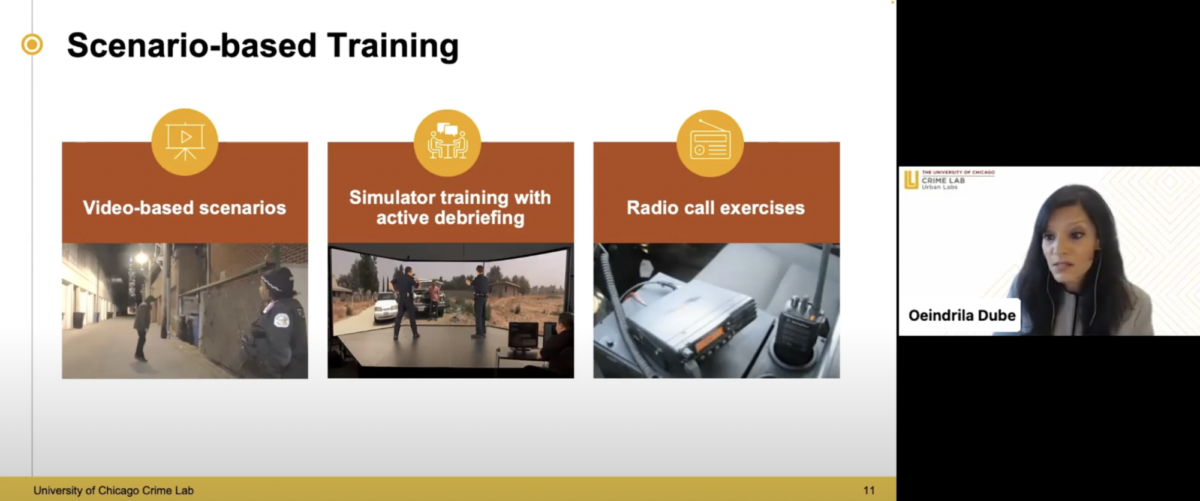

“We give [officers] techniques to avoid these types of thinking traps, and a key component of this is training them to rapidly consider alternative interpretations by having them engage in a variety of different scenario-based trainings,” Dube said.

To evaluate the effects of the training, Dube ran a randomized controlled trial with members of the Chicago Police Department. Out of 2,070 officers who graduated from the police academy and were going through service training, half of the officers received Sit-D training while the other half served as the comparison group.

The Crime Lab compared the performances of these two groups by testing how they responded to various scenarios. Dube and her team found that officers who went through Sit-D training were faster at deciding when lethal force should not be used.

Dube’s team also observed that officers were able to think of more ways to appropriately respond to situations. They were also able to gather more information about situations and decide on their interpretation of that situation faster than the control group officers could.

Dube claims that these positive benefits were seen not only in training scenarios but also in the field. Officers trained in Sit-D were 23 percent less likely to use force in non-lethal situations, 23 percent less likely to make a discretionary arrest, and 49 percent less likely to suffer an injury. Dube stated that these effects were gained without reducing how active they were in the field.

Dube stated that she and her team could not limit spillover effects from occurring in their study, as the Sit-D-trained officers and the control officers had to continue working together to maintain public safety and could not be separated for training purposes. This means that behaviors present in one group of officers may have spilled over to, or influenced, the other group. “That being said, what we can do now is look and see…if having a larger fraction of [Sit-D]-trained officers produces larger effects. We see definitive evidence that it does. What that suggests is that there are some spillover effects, meaning having more of the control officers limits the extent to which the trained officers are actually improving their outcomes.”

While this implies that the training may not be totally effective until a majority of the officers complete Sit-D training, Dube stated that this limiting effect meant that the data they gathered would only be a partial picture of the full extent of benefits. “Twenty-three percent reduction in uses of force are just an underestimate of the true effect [of the training]. The true effects are even larger than what these numbers suggest,” Dube said.

Sit-D training will require annual refresher training as its effects fade over time. “We see strong effects in the first four months after the training. Then, if we look in months five through eight and months nine through 12, the effects aren’t individually significant, but we can’t really say they’re actually significantly different from the first period effects, but [the effects] appear qualitatively smaller for uses of force starting in month five and for discretionary arrests starting in month nine.”