On May 17, I arrived at Doc Films to scratch out an end-of-year bucket list item: watch a movie on film. There, I saw West German director Ulrike Ottinger’s 1989 Johanna d’Arc of Mongolia. The film was introduced by cinema and media studies professor Daniel Morgan, who remarked that the last time he saw a screening of this film was 25 years ago as an undergraduate in a film studies class.

Johanna d’Arc of Mongolia follows a motley crew of European travelers on the Trans-Siberian Railway. The group, composed of the French Lady Windermere, a German school teacher, an American actress, and a Spanish girl, are forced out of their claustrophobic carriages onto the open steppes via a hijacking by Mongolian princess Ulan Iga. Taken hostage and brought to the princess’s yurts, the European travelers are pleasantly surprised by their captor’s hospitality. They share food and partake in the Mongolian summer festivities. A twist comes at the end of the film, when the European travelers find that the Mongols they have befriended were only upholding the illusion of a free nomadic life by living out their traditions. In reality, the narrator explains, the Mongols are an already “modernized” people. Leaving the steppes behind, Ulan Iga and the rest of the Mongols invite the European travelers onto their Trans-Mongolian Railway headed for Paris.

To call Johanna d’Arc of Mongolia merely a movie would be inaccurate. Instead, it is perhaps closer to an ethnography that tackles the problem of exoticism, forcing the audience to question their role as spectator. The film is part of a series of Ottinger’s work on China—the film takes place in Inner Mongolia, one of China’s “Autonomous Regions.” Through depicting the unfamiliar traditions of the Mongols, the film argues that cultural exchange is fueled by the exoticism of the unfamiliar, and Ottinger defends the morality of such exoticism via the idea of mutual exotic attraction.

Before going further into my critique, Johanna d’Arc of Mongolia is an anthropological wonder. The film captures many Mongol traditions, from their cultural rituals to the milking of mares for koumiss, a fermented milk drink. One of the most stunning scenes in the film is the skinning and gutting of a goat. Against a backdrop of verdant grasslands, a Mongolian butcher carefully ladles intestines into a brass bowl as a group of women sings hymns around him. The sanctity with which the Mongols treat their land is captured exquisitely. This is, after all, Ottinger’s intention as a director; by curating visual pleasure, she forces us to relish the role of a silent spectator.

I was captivated, but among shots in which the Mongols are depicted shouting and screaming, I couldn’t help but think about the intentional cultural estrangement that Johanna d’Arc of Mongolia conducts. Exoticism is the focal point of Ottinger’s films, but in depicting the perceived primitivity of some of the Mongols’ traditions, how does Johanna d’Arc of Mongolia deal with the responsibility of cultural representation?

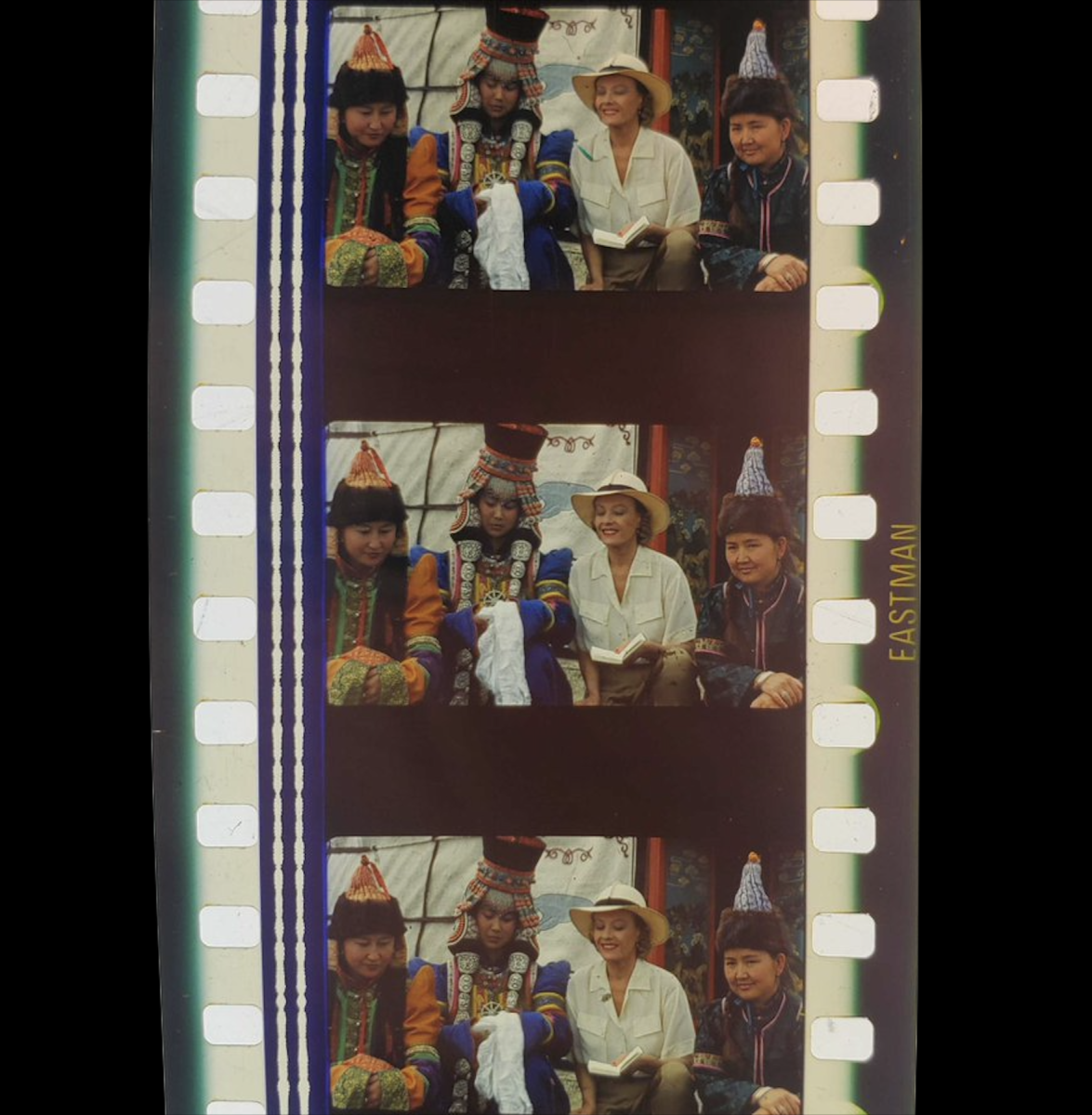

A Mongolian friend of mine, who was at the screening with me, commented that the film is mostly accurate in terms of the customs and traditions depicted but found the Mongolian dress questionable. It appears to be a small detail, but the idea that the Mongols were “costumed” throughout the film raises the question of what it means to estrange a culture against faithful representation. From a practical standpoint, the colorful Mongolian dress is perhaps excusable; some degree of glamorization contributes to a visually stunning film. However, the directorial decision to sacrifice authenticity when representing a culture carries the weight of implicit commentary.

To be fair, the decision to exoticize Mongolian culture is intentional on Ottinger’s part. After all, Ottinger is creating a critique on the role that exoticism plays in cultural dialogue. Perhaps we have to allow ourselves to engage in exoticism before recognizing it as an artificial lens. Nevertheless, in the course of her critique, Ottinger sponsors exoticism when she depicts it as a necessary ingredient of cultural exchange. How do we reconcile the role of exoticism in cultural exchange when it is fundamentally based on estrangement? Johanna d’Arc of Mongolia raises the question but does not seem to offer a complete answer.

Ottinger’s defense of exoticism’s morality comes at the end of the film, when she presents the Mongols as partaking in their own exoticism of European culture aboard the Trans-Mongolian. Speaking in English, Princess Ulan Iga tells Lady Windermere about her collection of European paintings. This moment is meant to represent the Mongols as equal players in the film’s exoticism, but it also contains an inherent irony. The Mongols’ capacity to engage in cultural dialogue is only realized when they become familiar to us. Throughout the film, the Mongols respond to the unfamiliar practices of the European guests, often with laughter, but they are not shown to process or comment on these practices in the same fashion as Lady Windermere does for the audience.

Princess Ulan Iga claims that in their summer palaces, they have pictures of Chinese princesses dressed in French rococo style, just as Louis XIV had pictures of French princesses in Chinese dress. Ottinger uses this line of dialogue to highlight the idea of mutual exotic attraction. However, when lifted out of the vacuum of the film, the idea of mutual exoticism is challenged by real historical context. There is an inherent power imbalance present in the history of colonialism, manifested in the one-sided looting of cultural artifacts, that goes against the reality that the film portrays.

Ottinger’s defense rests on the fact that the Mongols are equal players in exoticism, hence mutual exotic attraction, but this mutualism needs to be questioned. The point at which the film recognizes the Mongols as active players only comes when they have ditched their traditional dress and customs to assume European train uniforms. Could Ottinger have depicted the Mongols in conversation with the European travelers throughout Johanna d’Arc of Mongolia? Of course. This degree of integration would not constitute exoticism, though, as exoticism requires remaining on the periphery of cultural contact.

I don’t mean to put Ottinger in a catch-22. Can a film discuss exoticism without sponsoring it? And is exoticism inseparable from anthropological wonder? In Johanna d’Arc of Mongolia, Ottinger argues that exoticism is necessary and justified by mutual exotic attraction. I merely think that we should question that mutualism. At the very least, however, Johanna d’Arc of Mongolia is a remarkable film in its ability to raise questions about cultural representation that continue to be highly relevant 30 years later.