From the cool autumn street, the golden glow of electric light emanating from the tall windows of Seminary Co-op Bookstore promised a sanctuary of warmth and comfort—a promise that the rest of the evening would deliver.

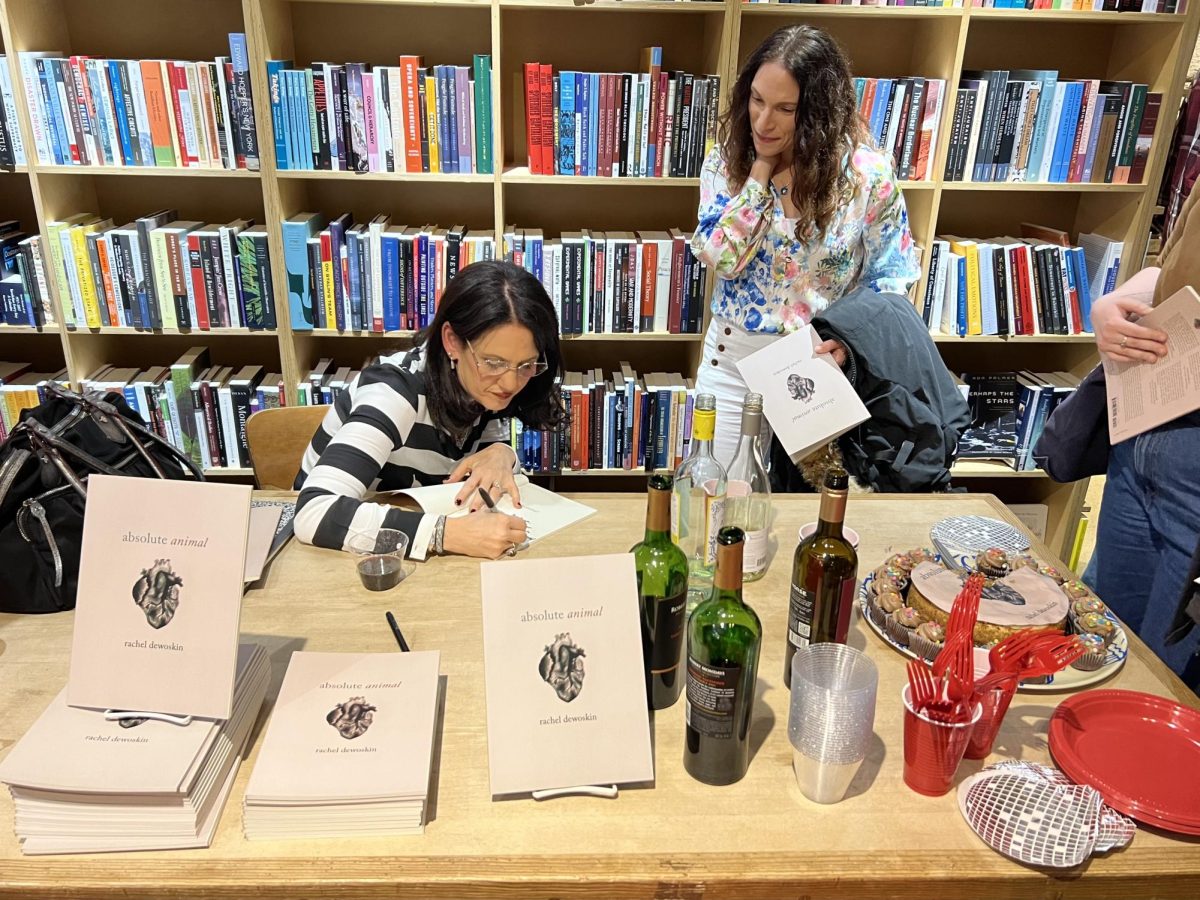

Walking in, I was hit with the rich aromas of books, cake, and freshly opened bottles of Cabernet Sauvignon. Admirers steadily trickled into the space over the following half hour. By 6 p.m., when the reading was set to begin, all 40 chairs set out were filled, and another 15 to 20 people stood in the back to hear readings from Rachel DeWoskin’s new collection of poetry, Absolute Animal. DeWoskin, author of five novels and associate professor of practice in the arts at the University of Chicago, began by reading eight poems from her new book, with accompanying photographs projected onto a screen. Then she sat down with the Poetry Foundation’s Ydalmi Noriega for a discussion and an audience Q&A.

The poems, ranging from strangely comic to haunting and melancholic, use formal poetic structures like sonnets and sestinas as containers for irreverent and at times chaotic streams of thought. In the middle of the book are translations of Chinese poems dating back to the Tang Dynasty. DeWoskin called the process “an Olympic sport. It is a challenge to try and get English words to do and to honor the varied work of Chinese characters. The density of the Chinese language is kind of impossible to translate to English, with its elegance and range of meanings.”

When asked to shed insight into her creative process, DeWoskin emphasized the influence of James Baldwin’s idea of “wonder as permission” on her approach to writing. “For me, wonder has always been the engine for my fiction and my poems. My work deals with ways to ask questions,” DeWoskin said. “Poetry is asking. Addressing and acknowledging chaos by way of rhyme.”

As a long line waited to get their copies of Absolute Animal signed after the discussion, the room exploded into chatter brimming with infectious enthusiasm for poetry. It was a rather moving scene that reassured me that I was not alone in my love of literature.

After the signing, I had the chance to speak individually with DeWoskin over a few slices of cake. I used the opportunity to ask for guidance on how writers like myself can deal with the damaging effects of literary obsession, the impulse to write poetry and fiction all the time. DeWoskin’s response was eloquent and encouraging, and I want to share it in its entirety:

“I think when you’re young that’s actually okay. Like why not, right? Now, you should sleep and eat. You should not do anything to the compulsive exclusion of sleeping and eating. Those are things you need to do to be healthy. And in order to make beautiful work you have to be alive. So survival is first, and then it’s making the work in whatever way works for you. But you know already as a young writer that there’s no one template for how to make work. People make work in all sorts of ways. Personally, I need love. I need an urban environment. I need my kids nearby. I need my husband. I need my parents in good shape. And then once I have those safe enclosures, I can work in a very focused way. And I write about chaos, and I write about fear, and I write about decay, and I also write about joy and love and the pieces of a human life, which are, of course, granular and profound.”

The prevailing spirit in the Seminary Co-op that night was one of great passion for storytelling as people ate and drank and laughed to the event’s close. I left with the gift of all the most wonderful art: a greater sensitivity to the very rhythms of life. The spell of the poetry reading lingered on, invoking in me an appreciation for a particular kind of quiet beauty on my walk home: the leaves rustling on the pavement, the low hum of passersby’s overlapping conversations, the fluorescent shimmer of string lights wrapped circuitously around half-naked trees on the quad, the empty benches cast in the faint semi-circular glow of old street lights, and the richly earthy smell of the autumn air.

Autumn quarter was coming to a close, cool temperatures were uniform through the Midwest, and I thought of planning an impromptu trip southward. As pale dusk leisurely made its way to night, I played the piano, repeating, again and again, the opening passage of Liszt’s Un Sospiro. Its melody ringing in my mind, I sank into a well-worn chair and opened up the books of poetry I had bought from the bookstore, a collection of Thomas Hardy poems and a copy of Absolute Animal. Losing myself in the rich and varied pleasures of these poems, I experienced once again what is in the end the ultimate gift of literature, the at once magical, mysterious, and miraculous power to transcend all boundaries and bind together generations of the living and the dead.

Ethan / Jan 21, 2024 at 10:00 pm

I appreciate the personal touch and expressiveness that came through here where it wasn’t necessarily as visible in other articles. I am struck by DeWoskin’s statement regarding the essence of poetry as one of asking, and (maybe, hopefully) addressing/acknowledging those same questions.