Don’t get hit by a car flying down the road. Don’t jump into a puddle. Don’t stand still for too long lest a bird attacks. This is what goes on inside the mind of a Crossy Road chicken, and also that of a Woodlawn resident on her journey to class every morning.

The sheer variety of things you encounter every day on the Midway Plaisance—cars, pond-sized puddles, flocks of geese, soccer goal posts, a monument to Linné—resembles the pixelated chaos of a game interface. A quick Google Maps survey leads to more questions than answers: Hyde Park Summer Fest Stage? The Chicago United Football Club? A skating rink?!

The Midway Plaisance clearly isn’t your average green space on a college campus. In fact, the Midway, despite its location at the center of UChicago’s sprawl, isn’t even owned by the University. Instead, it belongs to the City of Chicago and is maintained and operated by the Chicago Park District.

But living next to the Midway and being honked at by congregations of territorial geese can only advance your knowledge so far. Beneath that humble strip of patchy, muddy grass linking Jackson Park and Washington Park, Hyde Park and Woodlawn, there is a surprisingly grand story.

The Great South Park

Midway Plaisance was first conceived in 1869 as a connection between Jackson Park and Washington Park, funneling water from Lake Michigan and people from across Chicago into a massive envisioned South Side greenspace known as the “South Park.”

To lay out the project in 1870, the city of Chicago commissioned Olmsted, Vaux & Company, a prominent landscape architecture firm that designed iconic American public spaces like Central Park and Prospect Park in New York and the Emerald Necklace in Boston. Frederick Law Olmstead, the country’s preeminent park designer, envisioned South Park as a web of lagoons, bringing the waters of Lake Michigan into the heart of Chicago. The Midway would function both as a conduit of this water from Jackson Park on the lake through a canal to Washington Park and as a plaisance, an old French word describing a pleasing, secluded garden.

Olmstead’s vision for this undeveloped stretch of dirt on Chicago’s South Side was a grand one. “In the center will be a magnificent chain of lakes the entire length, bordered by planting spaces, adorned with exquisite flowers, trees, green swards, winding walks, etc. The lakes will be embellished with pretty bridges, beautiful fountains, artificial islands, white swans, etc.,” a newspaper kept in the Hyde Park Historical Society archive reported in 1875.

But construction in those years was slow. The Great Chicago Fire in 1871 had diverted money away from the South Park project, and development was delayed significantly and was halting even once work began years later.

In 1891, the city started prioritizing the South Park once again. The sprawling South Side green space was to host arguably the biggest event in Chicago’s history—the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. The eyes and people of the world would be clustered on the Midway.

Mudway Nuisance

In order to accommodate more attractions and visitors for the Columbian Exposition, the Midway, originally sunken due to its geology, was leveled by layering sand on its clay base. Since clay is impermeable, however, rainwater that collected on the Midway could not filter further into the ground. Water accumulated on the surface of the Midway instead, earning it the nickname “mudway nuisance.”

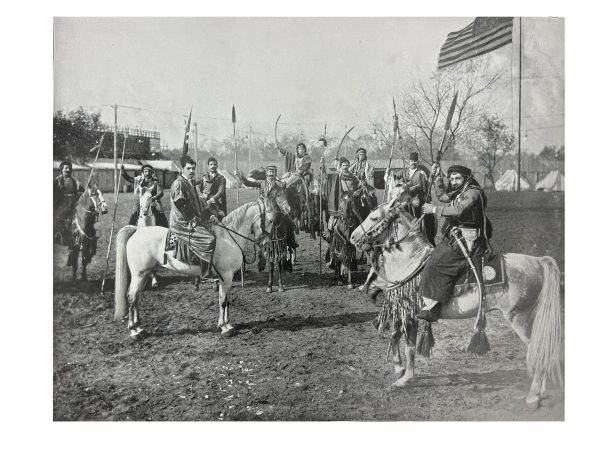

The Midway’s attractions were decidedly more lowbrow than the magnificent White City in Jackson Park, but it turned a handsome profit, and ‘midway’ became synonymous with any area in a fair providing fun and games. It featured the first Ferris wheel in the world, as well as ethnological exhibitions—“villages” recreating living scenes of different communities from all around the world. Old Vienna, for instance, had a row of Austrian-style buildings lining its side, while food stalls populated the central marketplace in an attempt to recreate the old city.

The influence of then-prevalent social Darwinism added a racist slant to the Midway’s exhibitions. The Exposition’s planners, led by Daniel Burnham, designed the Midway such that, as visitors walked from west to east through the Midway towards the White City, they would supposedly progress from “less evolved” societies to “more evolved” societies. American civilization, apparently, marked the pinnacle of human evolution.

Visitors were invited to observe a mock Chinese residence, showcasing the average Chinese woman’s “simple parlor slavery of the most agreeable type.” Arabs were “truly remarkable horsemen [who] deserve credit for that much, although there are characteristics peculiar to these people that are not particularly commendable.”

Public responses to the racist display varied during the time of the Exposition. Some framed the exhibitions as an intellectual inquiry into the evolution of human civilization—the visitor with a “scientific mind” could “descend the spiral of evolution, tracing humanity in its highest phases down almost to its animalistic origins,” the Chicago Tribune wrote in November 1893—while some considered it an invaluable opportunity to gawk at other cultures. “The Midway Plaisance is a sort of curiosity-shop, in which the curiosities are mainly men and manners,” Julian Hawthorne wrote in Lippincott’s Magazine in August 1893.

On the other hand, African American-run newspapers called out the organizers for their blatant racism. The Cleveland Gazette slammed the Exposition for being “the great American white elephant” in March 1893, and a group of civil rights activists—Ida B. Wells and Frederick Douglass among them—released a booklet titled “The Reason Why the Colored American Is Not in the World’s Columbian Exposition” the same year. The booklet’s exposition of racial discrimination in the U.S. to outsiders humiliated the organizers of the Exposition.

(Hyde Park Historical Society. Collection, Box 96, Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.)

Park for the People

Once the Exposition had ended in 1894, Olmsted wrested back control of the park and tried to realize his vision of the lakefront park network. Workers dug down the center of the Midway to make room for the canals, giving it the concave shape that we’re familiar with today.

Construction proceeded haltingly, with setbacks like fluctuations in Lake Michigan’s water levels and right-of-way issues with the Illinois Central Railroad (today the 59th Street/University of Chicago Metra station). By the time the Great Depression hit the country, South Park was no longer a top priority for the city, and the shortage of funds meant that neither of these problems were effectively addressed.

Another architect, Lorado Taft, presented a majestic plan for the Midway that involved magnificent fountains and bridges, including the Fountain of Time, which was unveiled in 1922. Unfortunately, his financial backer—La Verne Noyes, who also funded a building on UChicago’s campus in honor of his late wife Ida—passed away before Taft’s sculptural visions could be fully realized. Once again, an ambitious Midway project ended up forever midway through completion.

At the same time, the University was quickly growing beyond the capacity of the land that Rockefeller had originally provided. It expanded southward, and new buildings were erected along 60th Street: for instance, the Crown Family School was built in 1920, Burton-Judson Courts in 1931, and Harris School of Public Policy in 1988. Attention returned to the Midway as more people had to cross it every day.

In 2000, the Chicago Park District unveiled the Midway Plaisance Master Plan. The plan envisions the revitalization of the Midway to become a more accessible and welcoming space for the mid-South Side community.

“The development of park facilities, the improved management of traffic, and the creation of year-round gardens will support new and diverse programs that will draw people from all over the city,” the Master Plan’s Vision Statement read. “The plan will recreate the Midway; integrate it with the revitalized Burnham, Washington, and Jackson parks, and help make the South Side park system an exciting place for all Chicagoans to relax, socialize, and play.”

Evan Carver, an Assistant Instructional Professor on the Committee on Environment, Geography and Urbanization trained in urban design and planning, agrees that efforts have been made to make the Midway more conducive to social gatherings: the Midway now has activity hubs such as the skating rink and events like the Hyde Park Jazz Festival and the RBC Race for the Kids at Comer Children’s Hospital which bring people to the Midway.

However, these initiatives can only go so far. “I would argue that [the Midway] is not a highly functional public space,” Carver said. “The primary reason is that it’s cut off by two very busy roads.” The Midway was never designed to be pedestrian friendly to begin with. “The two one-way lanes, in terms of design, share more in common with airport runways than neighborhood streets. [They] invite cars to drive extremely fast, and pedestrians have to be brave and just hope that the cars stop,” he added.

However, the sheer quantity of students crossing the Midway every day has led to a qualitative change in how drivers and pedestrians interact. “The fact that there are more people on these raised crosswalks is a good thing [because that] reminds drivers that there are people walking here. Through a thousand little, tiny acts of rebellion, you guys forced the city to build crosswalks,” Carver said.

The second reason that the Midway is a dysfunctional public space, Carver argued, is that activities “have to follow historic preservation rules…It was built specifically for [the Columbian Exposition] 130 years ago, but there is no [Exposition] anymore.”

He considers the plan for a new universally accessible playground between Stony Island Avenue and the Metra tracks, however, a step in the right direction. “Playgrounds are extremely important for making a neighborhood family-friendly,” he said. “But if it’s still cut off [by car lanes] I can tell you I’m not excited [to] brave the 50 miles per hour traffic and stop signs with young children. It will probably get used more if it is contiguous with the neighborhood.”

Coming from Singapore, where there are designated “school zones” in which motorists must slow down, I’m still surprised that despite everything—the abundance of roads parallel to the Midway, the many young children attending the Laboratory Schools, and the historical significance of the Midway—the cars still seem to be the true “Monsters of the Midway.” Traffic accidents happen aplenty on the Midway. And all the signage in the world would do little to assuage the feeling that you’re nothing more than a Crossy Road chicken.

These road safety issues make the Chicago Park District’s vision for a pleasant Midway attracting people to actively come to it seem a little far into the future. But a brief survey of the past tells us how the Midway Plaisance of today has already vastly evolved since the days of playing host to Olmsted’s original plan or the World’s Columbian Exposition. Who’s to say the Midway Plaisance won’t truly be “a park for body, mind, and spirit” one day?

Laura / Jan 29, 2024 at 3:29 pm

Great article. I find it very depressing that Chicago treats its parks as just cut-throughs for cars. It is particularly absurd on the Midway Plaisance, which is absolutely a dysfunctional public space – hundreds of students crossing and just hoping that drivers going at high speed are paying attention and inclined to stop. Madness! We should push to completely pedestrianize/create a bike path on at least one of those roads, and install speed bumps on the other ones.