After first-year Alisha Arya committed to the University of Chicago, she opened the Class of 2027 Instagram page, eager to learn more about her new peers before the school year began. As she scrolled through her classmates’ profiles, however, she noticed nearly every post featured some variation of the same three words: “prospective economics major.” These words would only become more familiar once she arrived on campus.

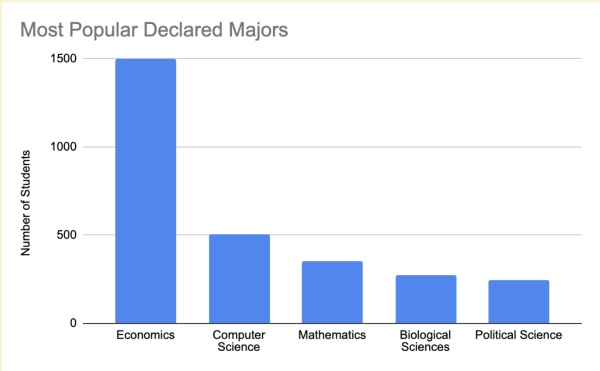

Having entered the College in the fall as an aspiring Psychology and Business Economics student, Arya was far from alone in her latter choice of degree. As of Winter 2024, 1,498 UChicago students have declared intent to major in Economics.

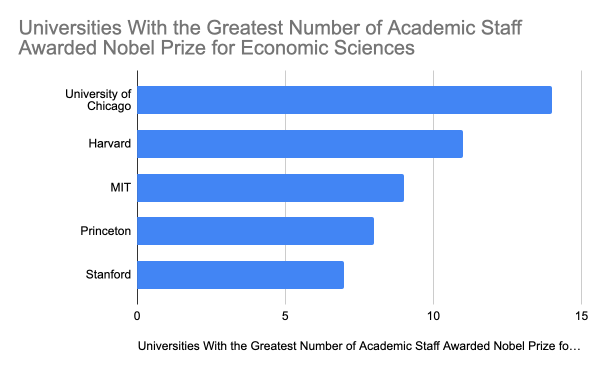

Professor Allen Sanderson attests to UChicago’s reputation for economics. “We have produced a large number of Nobel Prize winners and have had some of the best minds in economics for the last 200 years, from Milton Friedman to Gary Becker,” Sanderson said, referencing the fact that 35 percent of Nobel laureates in Economic Sciences have been affiliated with UChicago.

Sanderson added that the economics department’s relationships with other bodies on campus like the law school and the business school, have added to UChicago’s status as an “economics school,” such that there are several “centers” for economic study. In Arya’s view, it’s precisely this reputation that has created so many prospective economics majors.

“I think [there is] a kind of feedback loop of UChicago having such a cool economics program and a lot of students being driven here to UChicago specifically because of economics,” Arya said. “Even if they don’t start out with that [interest], I’ve heard many of my peers go ‘If I wanted to study something extra, the economics program here is wonderful, so I might as well take that up.’”

Also a business economics major, third-year M.R., who asked to remain anonymous to avoid backlash from classmates and clubmates, has observed the distinctive allure of UChicago’s economics program. To appeal to the university’s reputation for quirkiness, M.R. explained that some students will even deliberately indicate interest in “less popular” majors, attempting to improve their chances of admission and bypass the large pool of economics-interested applicants, only to switch to economics upon acceptance.

“[Many of the] students I know applied to UChicago because of the economics program,” M.R. said. “Of course, when we first apply no one has really decided on a major, but there are also people who got in for different majors. I’ve known people who applied for history [or] English literature, [but] it’s an application strategy to get around the group of applicants who are applying to econ directly.”

This “application strategy,” though perhaps useful at other institutions that admit by major, may not have a significant impact at UChicago, where students, aside from prospective molecular engineering majors, are admitted to the College as a whole, but many students, perhaps influenced by social platforms and peer advice, still believe in its effectiveness.

Regardless, M.R. has found that after acceptance, she and many of her peers switched to economics for the promise of a high-paying job after graduation, not because they actually “enjoy” it. At UChicago, economics is split into three tracks: Standard Economics, Business Economics Specialization, and Data Science Specialization. Of the three, business economics, which is M.R.’s chosen specialization, is viewed as the most overtly industry-focused, with its official description even declaring it best for students interested in “careers in the private sector, the non-profit sector, and the public sector” rather than academia.

According to Arya, industry connections and job prospects are also one of the main reasons why students covet membership in hyper-competitive finance and consulting clubs, herself among them.

“I think in order to get into these hyper-competitive [finance] jobs, you want a spot in one of these hyper-competitive groups,” Arya said. “A lot of these very competitive consulting clubs or finance clubs pride themselves on [their] networks and… [placements], [and] for those of us who already have careers and business school in mind, it is especially important to get an early start in that space. So, if we see a club that can give us experience, and give us a network or placement into one of these elite firms, it’s just a matter of doing whatever you can to build up your skills and get into that space.”

But for M.R., who has been a member of one of these clubs since her first year, they are often “overhyped.” She finds that these clubs try too hard to replicate the “highly competitive” cultures of traditional finance jobs—both social and professional— which has caused her stress in the past.

“[In my second year,] there were first years who came to me for advice about how to get into [one of those clubs],” M.R. said. “It’s really like a frat or sorority—just kind of a social symbol. Also, people would be really chasing after these so-called networking opportunities, but you can learn those technical skills by yourself. I can buy a modeling class on Wall Street Prep and learn everything. I mean, of course, working in a team and on a real pitch is very valuable, but I think the membership of these clubs is really overvalued [to the extent that] it is seen as the gateway into finance.”

Many of these preprofessional clubs also have large budgets—for example, The Blue Chips manage a $150,000 equity profile—which gives them hands-on access to investing scenarios that most students wouldn’t otherwise have the financial means to engage with independently. This, M.R. says, is where the real “value” of these clubs shines, and why, despite not always enjoying their competitive culture, she remains a member.

Likewise, though M.R. doesn’t always draw enjoyment from her economics coursework, her main intention, with both her major and extracurriculars, is to maximize her chances at obtaining a lucrative career in finance after graduation.

“[The business economics major] is meant to gear you up for finance jobs and [though] I did enjoy a lot of the classes [in economics], I definitely enjoyed my core classes more than the econ classes in general,” M.R. said. “[Still,] I’m just trying to get into investment banking.”

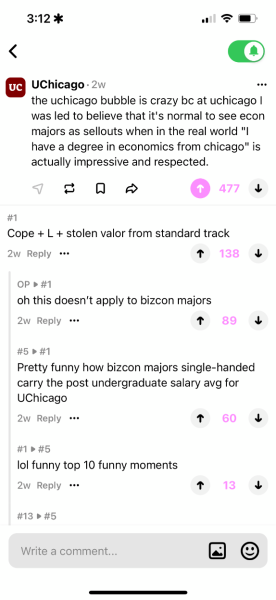

According to alum Jessica Zhong (A.B. ’23), however, this mindset isn’t always viewed favorably by the rest of the student body, with many referring to students like M.R. as “sellouts.”

“[Selling] out is students choosing their career based off of how much money they’re going to be making out of that career rather than a love or passion for the subject,” Zhong said. “I think, at UChicago in particular, it’s a controversial subject because we emphasize intellectualism and academics so much more than other institutions, so any student who chooses a more money-focused career stands out.”

Zhong added that this disdain for prioritizing money over passion is exacerbated by the fact that many UChicago students tend to be “privileged” enough to study more “esoteric, academic” subjects without considering salary, making those who choose to sell out stand out by contrast. However, she also notes that the business economics major is composed of students from all financial backgrounds, many of whom have parents already involved in the finance industry.

“There’s a level of affluence and privilege [at UChicago] that’s not reflected in the real world, where college is mostly seen as a pathway to a higher standard of living or a higher salary and that’s seen as respectable,” Zhong said. “In the real world, where the average salary is much lower, nobody can blame you for trying to improve your livelihood [by selling out].”

For Sanderson, too, this practicality-focused mindset is completely understandable. “[Rather than] ‘sell out,’ I would define it as: ‘economics [is] a really interesting field where I can get a job after I pay $70,000 for four years [and be able to] pay off my loans,’” Sanderson said. “People are just responding to that sentence: What’s the incentive?”

Correction, 04/21/24, 3:12 p.m.: An earlier version of this article misstated the number of first-year undergraduate students studying economics at the University. The correct number was published in the April 4 print edition, and the online version was updated on April 21, 2024.

Editor’s note, March 25, 2024: Following a source retraction, this article has since been republished with an additional source.

RPMartin / May 4, 2024 at 4:04 pm

As one who studied the Humanities at UChicago, I’m surprised at the number of students in fields like Computer Science. I hope they and those in fields which people have chosen because of prospects of high earnings will take advantage of the University’s prowess in the Humanities and Social Sciences — more than just what all undergraduates may be required to study as part of the Core.

Stop this nonsense / Mar 28, 2024 at 12:59 pm

This is an opinion piece, not investigative journalism. Who are you to call people sellouts because their priorities differ from yours, and are more aligned with practical needs? As people with your political outlook love to say – “check your privilege”.