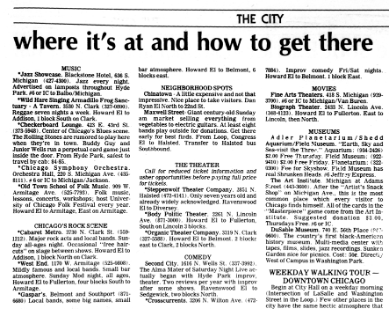

For decades, in Bronzeville on East 43rd Street, a blues-loving crowd of students mixed with locals at the Checkerboard Lounge blues bar. In 2003, the club was on the verge of shutting down. Aware of its popularity among students, the University of Chicago stepped in, offering to facilitate the relocation of the Checkerboard to Hyde Park, closer to the main student clientele.

A debate among the Bronzeville and UChicago communities, local businessmen, and musicians ensued. Can one export history? Transplant atmosphere? Relocated, the Checkerboard Lounge would not be in its original urban setting for all to discover, but instead delivered to students, at Harper Court, the newest addition to the University’s curated Hyde Park entertainment district.

In his book referencing the Checkerboard controversy, In the Shadow of the Ivory Tower: How Universities are Plundering Our Cities, historian Davarian L. Baldwin uncovers a larger trend of universities gaining control over urban governance, coining the phrase “the rise of UniverCities” to describe the process.

Would this be the Checkerboard’s fate?

First, its beginnings.

The Trip to the Original Checkerboard Lounge

“We immediately have to go past those red lines,” now professor at the Harris School of Public Policy Ethan Michaeli (A.B. ’89) and his friends concluded at the beginning of their freshman year. The university police had drawn red boundary lines on a map to mark areas they deemed unsafe, but “the greatest music on the planet” was a cab ride away, Michaeli reminisced in an interview with The Maroon.

Author Frank Luby (A.B. ’85) conjures up the cityscape on the journey to the Checkerboard in Blues Flashbacks: “The once-elegant, abandoned buildings, we rode past on the cab ride; a parking lot across the street with a huge chain-link fence topped with concertina wire.” A man stood, offering to keep watch over clubgoers’ cars for a four-dollar fee.

An “urban authenticity” was part of the Checkerboard’s allure. Nights spent at the club became ethnographic research for sociologist David Grazian’s (A.M. ’89, PhD ’00) Blue Chicago: The Search for Authenticity in Blues Clubs, which dissects the politics behind the consumption of blues music. He identifies the spatial proximity of South Side haunts to the Loop and the University as “a pull factor for many ‘slumming’ white artists, intellectuals, self-proclaimed socialists, graduate students, and pseudo-hipsters.”

At the Lounge, the motley crew gathered.

“What Gave It Away?”

One evening, Ethan Michaeli’s 16-year-old brother, visiting from New York, was swept up in the music. Magic Slim and the Teardrops were playing. “[My brother] started dancing very expressionistically, let’s say…he was taking up a lot of space on the dance floor,” Michaeli remembered.

“The older African-American adults who were there, in addition to the younger white folks like us, just clapped. Then Magic Slim noticed him and said, ‘This next one’s for my little friend’, and he played the song, ‘Ain’t It Nice to Be Up?’”

African-American youth spent nights at more fashionable places, listening to the 80s music in vogue, R&B and hip-hop, writer Max Grinnell (A.B. ’98, A.M. ’02) explained in a Maroon interview. A mix of older working-class African-Americans and mostly white students from nearby universities grateful to catch glimpses of blues royalty frequented the Checkerboard. By 1989, UChicago students made up 60 to 70 percent of the clientele, according to then-manager Ben Hampton.

Grinnell wondered whether, as students unaware of the “unspoken rules” of the Checkerboard, they were easy to single out. When Grinnell and his friends arrived, unsure of what to do before the show began, he went up to the bar and ordered a couple of glasses of water. “The bartender just said, ‘U of C students?’ I was like, ‘What gave it away?’”

“Somebody’s Living Room”

“Once we were in the door, a woman with an aluminum pan offered us some spaghetti,” Jay Jennings (A.M. ’81) recounts in an Oxford American article detailing his off-campus musical and cultural education.

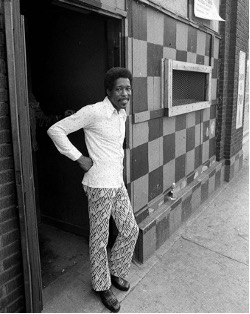

The club interior had a long, low stage, sitting at the end of skinny bar tables covered in red and white checkerboard tablecloths, just wide enough for playing cards and setting down a drink; stuffing spilled out of cushion chairs; Christmas lights and tinsel hung year round. A 1995 Chicago Tribune article notes that the homespun locale was more akin to “somebody’s living room or basement den than a bar. The walls are shiny, with a sparkle like angel dust, but you can also see hand-prints and smudges.”

Framed on the wall next to the door would have been a photo commemorating a November 22, 1981 performance when the Rolling Stones made an impromptu appearance during a night off from touring. The club’s founding overlapped with the tail-end of the 1960s “British Invasion,” when British rock and roll artists heavily influenced by blues musicians took the U.S. by storm. In a live video recording, a gyrating Mick Jagger, clad in a red tracksuit, stands between Muddy Waters and Buddy Guy and wails the blues. The historic set was immortalized in 2012 as an album, Live at the Checkerboard Lounge, Chicago 1981.

The Founders: Buddy Guy and L.C. Thurman

The Bronzeville mainstay’s first act was esteemed bluesman and co-owner Buddy Guy. He met future co-owner L.C. Thurman while working at Peppers, a blues nightery on 43rd Street. Guy’s nighttime stint as a guitarist and singer was sustained by a day job as a tow-truck driver. Thurman worked as a lab technician at a Veterinarian clinic at Northwestern.

In 1972, the two decided to start a club down the street from Peppers.

Twenty years earlier, Guy had arrived in Chicago, the last stop on the Illinois Central Railroad. Like many other Southern transplants, he came from a cotton-picking family in Louisiana. Between 1910 and 1970, in waves of mass exodus termed the Great Migration, 6 million African-Americans left the South of the U.S., where oppressive Jim Crow laws remained in effect, migrating to urban areas further north.

Guy arrived penniless in the “Black Metropolis,” where he befriended bluesmen on the scene. The young musician honed his craft as a backup guitarist for Muddy Waters, moving up the ranks as part of a new Chicago blues sound. Chicago blues emphasizes the backbeat and uses electrical instruments easily heard over the chatter of noisy juke joints, instead of the acoustic instruments of Delta blues. It is described as distinctly “industrial” because of the urban environment from which it grew.

L.C. Thurman, described as a “private” man in a 2015 DNAInfo article, was not a performer and focused strictly on running the club. In 1985, when Buddy Guy broke off the partnership to establish his own blues bar closer to downtown, L.C. Thurman became the sole proprietor of the Checkerboard. (The split has not been written about in detail.)

The Lounge was the pair’s contribution to keeping the tradition alive in the South Side cradle where it had been shaped and nurtured, even as sleek, commercialized North Side and downtown digs were better designed to achieve financial success. “The pay might be better on the North Side,” a 1984 Chicago Tribune article quotes singer Lefty Dizz after a performance. “But it feels good to be back here with my friends.”

Exporting History

A shared appreciation for the music energized performers on kinetic nights. But by the 2000s, genres such as disco and R&B captured the zeitgeist, and interest in the blues dwindled. In 2003, paying venue rent he couldn’t afford and burdened with an unrepaired roof leak that had persisted for years, L.C. Thurman set a deadline.

Each year at the club, Thurman celebrated his birthday. If his landlord wouldn’t agree to lower the rent by the planned March 23rd festivities, he would close his doors for good.

Then UChicago approached Thurman with an offer. For $7 per square foot or around half the market price, Thurman could relocate the club to Harper Court Mall as part of a “re-imagined” 53rd Street development, courtesy of the University.

Chairman of the Committee to Restore Jazz in Hyde Park James Wagner first put Thurman in touch with University representatives. As the University had recently begun investing in developing local cultural institutions, UChicago Vice President of Government and Community Affairs Hank Webber saw an opportunity to preserve a piece of American blues history. Community advocates asked why the University couldn’t fund a restoration project instead of facilitating the Checkerboard’s relocation. In proposing to transplant the club, they felt the University had commodified the blues into a cultural export they wanted to claim for themselves.

Some, including founder of Alligator Records blues label Bruce Iglauer, wondered whether the essence of the Checkerboard —what he called “the slapped-together, casual, funky feel”—would be lost. He pointed to Peppers, which had lost its audience when it relocated to Michigan Avenue.

“I’d go to Winnetka if I could get my club open,” Thurman responded. Besides, most of his patrons were UChicago students, he reasoned in a 2003 Crain’s Business article.

In the months following the offer, a group of Bronzeville residents protested the move, accusing UChicago of making a sweetheart deal, or a contractual agreement that greatly benefits some parties while disadvantaging other parties, “stealing” a cultural institution.

The Maroon’s editorial board argued that the move would help launch the Checkerboard into the modern landscape. Their op-ed, entitled “Checkerboard protesters misguided,” retorted that the “Home of the Blues” without a home was a “moment lost in time.” Michaeli agreed. “I think the University rescued the Checkerboard when it facilitated their move to 53rd Street. I think it would have shut down sooner had the University not done that,” he said.

The original location wasn’t ideal. “It had its charm, but it was, you know, a fairly dangerous part of the city, and got more so as other businesses in that little part of 43rd Street dwindled and then disappeared,” he continued.

Michaeli instead attributed the ultimate 2015 closing to a change in musical tastes and the lack of coordinated efforts by schools, local governments, and other players to invest in preserving the Chicago blues.

The New Checkerboard Lounge

The new Checkerboard Lounge opened in Harper Court two years later on a Thursday night in November of 2005. Local blues singer-pianist Jo Jo Murray and his Top Flight band performed a set of straight-ahead blues. But the new spot—tidy, spacious, chic—was unlike the old. Thurman prepared for a new chapter in the Checkerboard’s history. He warmed to new business practices, updating his performer lineup to more frequently incorporate acts other than blues. A 2006 Chicago Tribune article documents that, in the year following the move, the club was attracting a “good neighborhood audience,” but not the kind of turnout Thurman had expected from the university crowd.

Momentum didn’t build.

Paying musicians and turning a profit grew unfeasible. Grinnell once arrived at the club to find the doors locked when the schedule had advertised live music. “Even though they had a long and venerable history, given the kind of less than robust calendar performances, I don’t think people felt like they could count on them,” Grinnell said.

Some believed the club had been closed instead of relocated due to a lack of communication with the public. And when university real estate ambitions pivoted in November 2012, the conversion of part of the Harper Court retail center into an office tower began, which obstructed the entrance to the club. For those in the know, getting in, for a time, was nearly impossible. “The construction site was literally at the club’s doorstep, forcing the club to flip its entrance and marquee to the opposite side of the building,” Thurman’s brother Maloid Jones explained in a DNAInfo article.

The stress of keeping up the establishment took a toll on Thurman’s health. After a struggle with an unspecified illness, he passed away on July 22, 2015, and the Checkerboard Lounge shut down—permanently.

“Still Got A Hold On Us”

“The Checkerboard should still be there as the University of Chicago of the blues, training people, new generations of musicians. It should be bringing in audiences,” said Michaeli. Its legacy continues, quietly. “The blues is the same story over and over again,” songwriter Willie Dixon philosophized. When one raconteur tires, another one takes over.

Storied blues bar Lee’s Unleaded Blues recently had its soft reopening on April 26th in Grand Crossing. Architect and professor Andrew Schachman (A.B. ’91) frequented the Checkerboard in his student days and mused that Lee’s has the potential to acquire a reputation among UChicago students similar to that of the defunct lounge, although the hole-in-the-wall joint flourished under conditions that no longer exist. Nightlife teemed with jazz and blues clubs, witnessing musical innovators at work was common, and the minimum drinking age was 18, before it was raised in 1984. ID checks also happened less frequently. Michaeli’s 16-year-old brother was easily granted admission to the Checkerboard.

Nowadays, the Logan Center Blues series provides on-campus entertainment. Owner of Lee’s Unleaded Blues Warren Berger observed a relatively small number of young blues fans and a mostly older local crowd attending a recent Logan Center Tuesday Blues performance. About his club Lee’s he expressed: “I’m excited. Every time I talk to people, they’re excited by it…not so much young people, because I don’t talk to that many young people.” Still, the 77-year-old welcomes the elusive demographic. “I’m hoping that U of C students will come out,” he told The Maroon.

South Side blues bars, Max Grinnell reflected, “have mostly disappeared.” But the Checkerboard isn’t exactly a moment lost in time. Like a phrase of a blues song that lands in the middle of another tune, slightly altered, relics reappear in modern settings. A photo of Mick Jagger standing behind Muddy Waters hangs on the wall at Lee’s, commemorating that serendipitous night in 1981 at the Checkerboard Lounge.

Summa / May 10, 2024 at 9:33 pm

Well, I am returning to Hyde Park for my 50th reunion (College class of ’74) in a week and I have many fond memories of the original Checkerboard. Whenever I made enough spending money hustling pool in the basement of the Reynolds, I made a beeline on Friday nights to 43rd. As a Philadelphia white boy, I knew how to keep up (barely) on the dance floor with the “ladies of the night” when they made their appearance after midnight. I learned a whole new level of moves. RIP Checkerboard. xoxo