The first thing we noticed when we crept into the Ryerson basement was the scent of dry concrete and industrial musk.

The old metallic scents are fitting for the basement’s low ceiling crisscrossed with pipes, its dusty floors littered with long-forgotten debris, and the hum of machinery ever-present within its aged walls. Along the corridor, forgotten classrooms hide behind worn wooden doors, and as we peer into their darkened entryways, only empty interiors and repurposed utility rooms stare back. No lectures take place here anymore.

Like many buildings on campus, Ryerson’s history hides in plain sight. Thus began our journey down a rabbit hole of research and exploration, all in hopes of discovering what makes UChicago’s secret places so special today.

Ryerson Laboratory

Built in 1894, the Ryerson Physical Laboratory originally shared its classes with the Astronomy and Mathematics departments. However, demand for lab space quickly outgrew the size of the facility.

In 1912, Ryerson grew with the construction of an annex, but it was not until Eckhart Hall was built in the 1920s that the problem of overcrowding was finally resolved. Until then, the basement of Ryerson simply served as extra space for laboratories.

An article published by The University of Chicago Magazine in December of 1912 reflects on the annex as well as renovations made to its foundation level, saying, “The basement floor has been lowered a foot and a half, and thus twelve new research rooms have been secured.” These rooms, as a result of their stability and consistent temperature, offered an important regulated atmosphere for delicate research. This made the Ryerson basement a key location for physics research throughout its history.

Today, the classrooms on the ground floor are unused and the basement has been repurposed for utilities and maintenance.

Walking through Ryerson today, many of the classrooms contain well-preserved pieces of their past: there are room numbers on the doors, chalkboards on the walls, and old desk chairs scattered throughout. While the Ryerson basement may be nothing more than the skeleton of a once thriving lab, these remnants keep its former existence intact.

Ida Noyes Hall

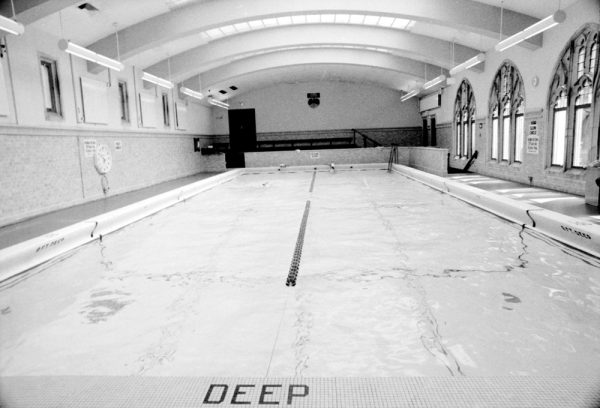

Although Ryerson may have been the first secret place we discovered, it certainly wasn’t the best hidden one. An abandoned pool with an unexpected history lies within Ida Noyes Hall. In the 1910s, facilities such as Bartlett and the Reynolds Club were exclusive to male students. As an alternative, the University constructed Ida Noyes Hall in 1916 to serve as both a clubhouse and a gym for female students. A prime feature of this new building was a 20-yard, four-lane indoor swimming pool adorned with oak wainscoting, iron rails, and a gessoed ceiling.

Over time, the pool’s purpose changed. Ida Noyes became a training spot for the water polo team as the other athletic facilities began to provide all-gender pools for the rest of the students. The Ida Noyes pool eventually went into retirement with the construction of the Ratner Athletic Center. It was drained and abandoned but never demolished. This now begs the question: Where is this pool?

While the University has stated that the hall’s gym now stands as the Max Palevsky Cinema, the fate of the pool remains more hidden. A Weese Langley Klein architecture firm article from 2008 explains plans for a “renovation convert[ing] a former swimming pool into a study hall for the neighboring University of Chicago Graduate School of Business.” Some students have found that the pool referenced is indeed the same pool from all those years ago, now sitting underneath the Booth study space.

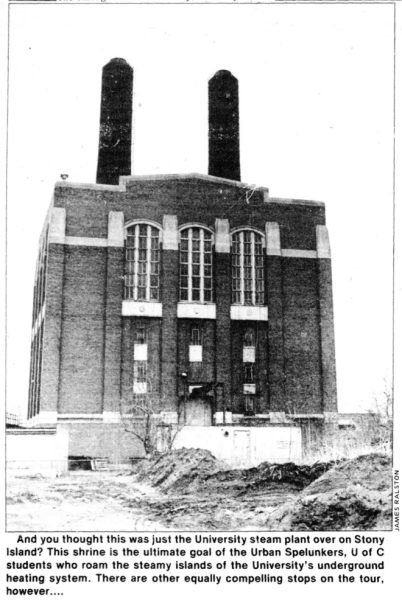

Steam Tunnels

Some secret places seem entirely impossible to reach. Just beneath our feet, a large network of tunnels distributes steam and gas from the University’s resident generator to heaters and showers. The original steam tunnels date back to 1929, though in 2009 and 2010 the South Campus Chiller Plant (SCCP) and West Campus Combined Utility Plant (WCCUP) completed construction and took over the main role of steam distribution.

The SCCP remains a notable addition because it stands right next to the original 1929 steam tunnel building. Located on Blackstone Avenue and 61st Street, its minimalist glass design stands in contrast to the industrial brick and steel of its older counterpart. However, the buildings themselves are just the beginning of the steam tunnel’s extensive history.

Through the years, UChicago’s steam tunnels have hosted their fair share of eager explorers. Although an article released from UChicago’s office of sustainability claims that any entrances to the tunnels were sealed with locks, stories of students breaking in are scattered across the internet.

A Maroon article released in 2010 describes two students finding ways into the tunnel system, stating that “the most obvious entrances, however, are grates fitted with Lev-L-Locks, which they opened from above with a crowbar;” on a blog, an alum quotes a 1999 Chicago Magazine article in which a steam plant manager “reported finding beer bottles and graffiti in the tunnels;” and in a 1985 issue of the Daily Maroon, one student even describes the lessons he learned about heating technology through his own experience sneaking into the tunnels in an article titled “Urban Spelunking: the underground guide to higher education.”

Despite the passageways reaching up to 120 degrees Fahrenheit, a temperature hot enough to cause third-degree burns, the steam tunnels’ secretive allure has enticed generations of UChicago students. Today, the steam tunnels do more than just heat our buildings: they bring a piece of adventure to every corner of the campus.

Harper Library

Our hunt for the hidden finally led us to the Harper Library: a University landmark home to not one, but two secret locations.

A library beneath a library, the first secret place of Harper is its basement. The building was constructed in 1910 as a memorial to the late William Rainey Harper, who believed that the school needed to provide its students with a dedicated space for academics and learning.

Although Harper Library still stands to this day, the basement was closed to the public in 1971. With the construction of the Regenstein Library that same year, a majority of Harper’s overwhelming collections were transferred to the new building, likely placing the basement into retirement. Direct accounts of the basement during its operation are scarce. However, recent explorers have discovered that many old relics remain. In 2018, a student published an article on Medium describing their expedition beneath the floor of Harper. Amid dusty walls and flickering lights, they discovered books still resting on once overflowing shelves, and documents dating back to the 1940s littered across the floor.

The second secret place is located in Harper’s ceiling. What makes this ceiling particularly noteworthy is that between the curved ceiling of the reading room and the peak of the roof itself, there exists a hidden space. A previous explorer explains in a blog post that to reach the ceiling, they had to venture up the West Tower (this tower originally collapsed in 1911 but was swiftly rebuilt).

一一一

For the people who continue to seek out their existence, these places spark curiosity and remind all that their legacy remains alive. Generations of students have left their mark, and generations more will continue to do so. In the end, their history remains an embodiment of the students that shape their stories.

As for what makes UChicago’s “secret places” so special today? That’s for our curiosity to decide.

Bob Michaelson / Feb 18, 2025 at 3:56 pm

“The second secret place is located in Harper’s ceiling. What makes this ceiling particularly noteworthy is that between the curved ceiling of the reading room and the peak of the roof itself, there exists a hidden space. A previous explorer explains in a blog post that to reach the ceiling, they had to venture up the West Tower (this tower originally collapsed in 1911 but was swiftly rebuilt).”

Some more information for you: the ceiling is made with Guastavino tile, a thin, light-weight tile also used in Rockefeller, which can be assembled without falsework. Because this tile was used, it was possible to put high intensity lighting into the Reading Room ceiling (late 1960s?).

The cause of the collapse of the West Tower was never determined.

ariana / Feb 17, 2025 at 8:13 pm

great read!

Dave / Feb 17, 2025 at 8:09 pm

This article brought alive events and stories these buildings, tunnels, and hidden walls have witnessed. Carter and Kaci, I look forward to reading more of your work and learning about hidden gems of UChicago!