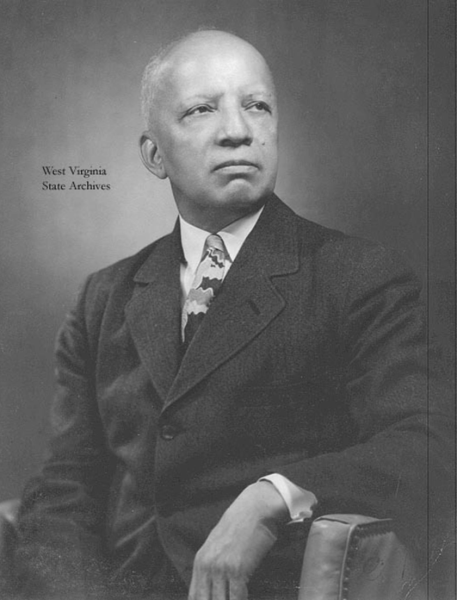

Carter G. Woodson (A.M. ’08), was a historian, author, and educator whose commitment to the study of Black history led to the creation of Black History Month. After completing his undergraduate degree in literature from Berea College in Kentucky, Woodson obtained his master’s degree from UChicago in 1908. He then became the second Black American to get a Ph.D. from Harvard, second only to W.E.B. Du Bois.

In 1926, Woodson introduced Negro History Week, selecting the second week of February to coincide with the birthdays of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln. While Negro History Week was never on the national calendar, his efforts laid the foundation for what is now recognized as Black History Month.

In honor of Black History Month, Grey City examined the Maroon archives to trace the history of dormitory segregation and desegregation at UChicago. The story of dormitory desegregation is an early example of students and faculty challenging the University to confront its institutional barriers and push it toward greater inclusivity.

Georgiana Rose Simpson, Early Struggles with Housing Segregation

(Leah Tabakh)

Georgiana Rose Simpson was the first Black woman to graduate from an American university with a Ph.D. in 1921.

In 1911, Simpson received a Bachelor of Arts in German at UChicago. She then received her master’s degree, also at UChicago, in 1920. Her master’s thesis examined an early Middle High German poem. Simpson completed her dissertation, “Herder’s Conception of ‘Das Volk’,” and received her Ph.D. in German on June 14, 1921, at age 55.

Simpson experienced racial prejudice while living in UChicago dormitories. When Simpson moved into a majority-white dormitory, her white neighbors protested. At first, Sophonisba Breckinridge, the residence hall head, advocated for Simpson. But after five white women left the residence hall, Breckinridge asked Simpson to leave the dormitory. Simpson refused, and Breckinridge rescinded the request. However, University President Harry Judson ultimately intervened, forcing Simpson to vacate. As a result, Simpson took most of her courses during the summer to avoid further conflict.

After Simpson died in 1944, Breckinridge published Simpson’s obituary in The University of Chicago Magazine. Breckinridge wrote that Simpson’s death left her with “a sense of real personal loss” and that “during the years since the summer of 1907, when I first became acquainted with her, I have cherished the highest respect and a warm and affectionate regard for her.”

In 2017, the Monumental Women Project honored Simpson by commissioning a bust of her in the Reynolds Club. This bust is now standing directly across from a relief of President Judson.

1962–1963: University Admits to Housing Segregation, Protests and Sit-ins Follow

On January 17, 1962 the Maroon published the news that “UC officials admitted yesterday that Negroes are barred from living in several buildings owned by the University.”

Before the article, the University had never publicly acknowledged its discriminatory housing policies. However, as Simpson’s experience illustrates, segregation in student housing had been an ongoing issue for decades.

According to the same article, “charges of UC segregation were first presented by a group representing Student Government and UC’s chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). The group sponsored test cases in which Negro and white students applied for apartments in University-owned buildings. In each of the six cases, Negro students were refused apartments, while white applicants were offered apartments.”

The results of these test cases provided undeniable evidence of racial discrimination in University housing policies. Following the article, protests surged across campus, culminating in the University’s first sit-in protest. On January 23, 1962, roughly 30 students participated in an all-night sit-in outside former University President George Wells Beadle’s office in the Administration Building to demand an end to racial discrimination in housing. Bernie Sanders (A.B. ’64) and Bruce Rappaport (A.B. ’64) led the sit-in as leaders of UChicago’s CORE chapter.

The Maroon continued to document the mounting tensions between students and the administration as activists pressed for immediate desegregation in the early 1960s. On July 19, 1963, the Maroon reported that the University had officially ended housing segregation. The article quoted Beadle’s statement on the ending of housing segregation: “There are currently no racial restrictions in any University-owned buildings.”

The struggles and triumphs of Black students, scholars, and activists have shaped UChicago’s institutional history. As community members continue to challenge the University’s institutional barriers, Black History Month serves as a reminder of this ongoing struggle and celebrates the contributions of those who fight for recognition, equity, and justice.