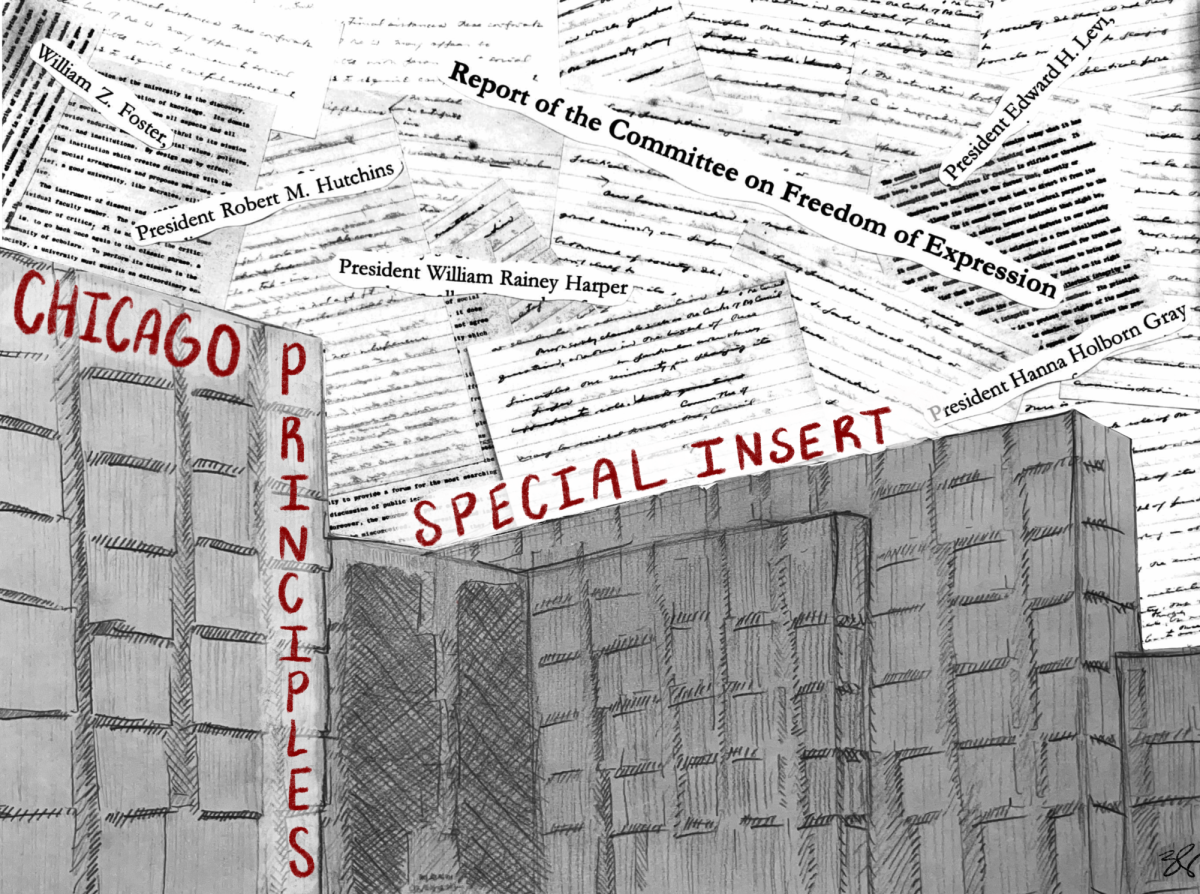

Since its publication 10 years ago, the Report of the Committee on Freedom of Expression—commonly known as the Chicago Principles or the Chicago Statement—has become a touchstone for the debate over free expression on college campuses.

Over 100 U.S. universities and colleges have adopted or endorsed the Principles, praising them for avowing an ethos of higher education. Amid student protests last spring, students and faculty criticized the report for hindering the very freedom of expression it claims to promote by enabling administrators to sidestep difficult questions in the name of the Principles.

In drafting its report, the Committee consulted a second text at the heart of discourse on academic freedom. The 1967 Report on the University’s Role in Political and Social Action, or the Kalven Report, recommends that UChicago maintains neutrality as an institution on most political and social issues to allow its members the fullest freedom of individual expression.

Though oft-cited, the Kalven Report and the Chicago Principles are little read. As a result, the intricacies of both reports are frequently overlooked in favor of their broader statements.

In reporting on the documents, two facts became clear. First, the authors of both the Chicago Principles and the Kalven Report intended to write living documents for future generations to reassess—an objective their adopters have sometimes disregarded. Second, both documents contain unresolved tensions and fail to answer questions the drafters could not foresee. Academic freedom, as many have argued, is increasingly a privilege not afforded equally to all members of our community.

With this special insert, we hope to renew the dialogue around a pair of documents that often have hardened into a creed.

The insert opens by revisiting the Kalven Report. The Maroon annotates the 1967 document by drawing upon hundreds of pages of committee chair Harry Kalven Jr.’s papers and an interview with his son, journalist Jamie Kalven.

You will also find reflections from members of the Chicago Principles Committee; conversations about the complications of free speech in the digital age and in medicine; and discussion of the danger of pre-emptive self-censorship and institutional timidity in the face of attacks on higher education.

With the reelection of President Donald Trump, the very mission of higher education is at stake. The Trump administration has targeted federal research funding and diversity, equity, and inclusion educational programs, stifling expression and scholarship. At this crossroads, the University has the opportunity to set an example for other institutions once more by demonstrating its commitment to academic freedom.

In a letter to fellow committee members, Harry Kalven Jr. calls the 1967 report a “stimulus for discussion.” We welcome readers to the Chicago Principles Special Insert, a point of departure for dialogue.

Anushree Vashist, 2024–25 managing editor

Celeste Alcalay, Grey City editor

Matthew G. Andersson, '96, Booth MBA / Mar 10, 2025 at 8:36 pm

The fascinating aspect of the “Chicago Principles,” is that they even exist at all. Would a statement that declares different opinions tolerable, be taken seriously if the subject were physics? Or astronomy or engineering? Why is it necessary to formalize, at an institution of higher learning, a willingness to invite all viewpoints that contribute to knowledge? Since when do we think it noteworthy in America, that a university “allows” different perspectives? What good, then, are the Chicago Principles and the Kalven Report? Free speech is not an accommodation of opposing viewpoints, but an organizational configuration that comprises tangible heterodoxies, created by hiring and behavior. Little heterodoxy exists at UChicago, either within faculty, or administration. It is signaled disingenuously through “centers,” “institutes,” and “forums,” which are faculty make-work platforms. In the case of the Forum, it is merely a repurposed cost center for a building left vacant by the shuttered “Institute for the Formation of Knowledge.” The Principles otherwise have some marketing utility, but in its institutional culture, UChicago is part of the ideological uniformity of higher education. This is a problem ultimately of leadership. The President’s office is currently vacant in this, and other dimensions. See “UChicago Isn’t Living Up to its Principles,” at James G. Martin.