The Chicago Principles were published in 2015 after then-University President Robert Zimmer and Provost Eric Isaacs appointed a committee to author a statement articulating the University’s commitment to “free, robust, and uninhibited debate and deliberation” among its community members. The Maroon asked members on the original committee to reflect on the report, which has drawn controversy and praise alike over the last decade. (Six of the seven members responded; Lindy Bergman Distinguished Service Professor of Medicine and Surgery Mark Siegler was not available for an interview.)

The Committee convened in 2014 due to “recent events nationwide that [had] tested institutional commitments to free and open discourse,” according to the report.

In a season of protest, campus activists across the country were calling for controversial commencement speakers to cancel their scheduled visits. The advocacy group Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE) filed lawsuits against four universities in an effort to force them to revise policies FIRE claimed had restricted some forms of speech. At the University of California, Berkeley, marches against police violence swept across campus, blocking traffic in both directions on Interstate 80.

“There was a general sense that expression was being restricted on college campuses in various ways,” Dean of the Division of the Social Sciences Amanda Woodward told the Maroon.

“I do remember, in particular, the controversy around freedom of speech at Yale was one of the things we looked at,” Fairfax M. Cone Distinguished Service Professor Kenneth Warren recalled.

In January 2014, Yale’s administration made the controversial decision to shut down Yale Bluebook+, a student-generated course catalogue that used university material to rank courses, due to concerns about improper usage of licensed material. Yale’s own policy on freedom of expression emerged from a report by the Committee of Freedom of Expression at Yale in December 1974.

For much of the 20th century, free speech was a rallying cry for the left to defend communists, pacifists, and anarchists, writes Sophia Rosenfeld, a history professor at the University of Pennsylvania. More recently, the political right took up the mantle of free speech, while the left endeavored to protect minorities against hate speech. The roles reversed once again with last spring’s nationwide pro-Palestinian encampments, as protestors demanded their universities protect the speech that conservatives were denouncing.

“I think that in 2014 what was thought of as objectionable came from a different part of the political spectrum,” said Gerald Ratner Distinguished Service Professor of Law David A. Strauss.

Within the walls of the University, the Committee was not focused on the political issues of the day, it said. Although they resided in different academic corners of the University, Committee members agreed on the thesis that would lie at the heart of the document.

“We had the experience of ourselves growing up in the culture of this place,” said Woodward, who has spent most of her professional life at the University.

Committee members described the influence of free speech principles on their own lives.

“I lived the Title IX issue, let’s put it that way, and it was not pleasant to have male faculty say that women should not do theoretical physics, which they did say,” said Provost of Columbia Angela Olinto, who was an astrophysics professor at the University in 2014. “I would love to be able to stifle that kind of expression.”

However, Olinto argued that in many instances, engaging in dialogue is the most effective response to speech one doesn’t agree with. “You have to argue the case,” she said.

Like Olinto, Committee Chair and Edward H. Levi Distinguished Service Professor of Law Geoffrey Stone holds an almost religious belief that freedom of expression in a public forum leads to change over time.

“We have changed our mind about many things over many years, whether it’s about race, about racial discrimination, about gender roles, abortion, sex, sexual expression, partly because we’ve been exposed to competing ideas,” Stone said. “And so that’s an essential part of a democracy, and it’s an essential part of a university.”

Woodward witnessed and practiced free inquiry in her routine teaching and research duties, so much so that, at the very beginning of the drafting process, she struggled to recognize that faculty new to the University weren’t as deeply embedded in the same culture.

“I didn’t really understand that there was a kind of urgency [here] around reflecting on the importance of free expression, and that the University of Chicago’s values weren’t obviously shared… and they certainly weren’t necessarily shared by other university communities,” she said.

Notably, the Committee was writing for the immediate University community, not a national audience.

“I have to say, when we wrote the report, we were not thinking about anybody else adopting it,” Stone said.

Its task, the Committee felt, was to reflect on the unique culture of freedom of expression that had long been upheld at the University.

“We didn’t invent the Chicago Principles,” Woodward said. “In fact, if you look at the document, it’s a set of quotes, beginning with the first president of the University of Chicago and going through to the present day, quoting president after president, faculty leader after faculty leader,” she said.

The University of Chicago is known for welcoming free exchange of ideas of the most radical sort. In 1932, students invited Communist Party presidential candidate William Z. Foster to speak at the University. In his speech, Foster called for the abolition of capitalism. In 2017, Stone declined neo-Nazi Richard Spencer’s request to speak on campus but noted if another member of the University chose to invite Spencer, he would have defended Spencer’s right to speak on campus. In an oft-referenced 2016 incident, the University sent a letter to incoming students decrying safe spaces and trigger warnings.

Strauss reflected on the negative connotations that have accompanied the University’s absolutist philosophy of free speech and defined its reputation.

“Some people think… that [UChicago] is a place where people are kind of nasty or even abusive, and then they justify that by claiming, ‘Well, I’m just presenting an idea,’” Strauss said.

The University of Chicago community is well-positioned precisely because of that association to dispel the notion that freedom of expression is synonymous with vitriol, he said. “We have the ability to show that that’s all wrong. We can model exchanges that demonstrate that there is no inconsistency between taking ideas seriously, engaging in vigorous debate, and treating people respectfully.”

More than 100 universities have adopted versions of the Principles, and the drafters say it is sensible for each school to follow an individual process of reflecting on their set of values.

“Not all academic institutions share the same values, and some of them may well think that it’s inappropriate, for example, for students or others to say things that offend other people—and that would not be consistent with the First Amendment as it currently exists,” Stone said.

Stone’s reading of the Chicago Principles, like the First Amendment, allows for very limited exceptions in which speech might be curtailed.

The drafters also reiterated that the document only serves its intended function when an underlying culture of commitment to the principles persists.

“They’re principles, and they aren’t going to give you specific answers to specific issues that come up on campus. So what follows from that is that the culture that the university creates [around expression] is really critical,” Strauss said.

While they didn’t call the Principles a cure-all, some of the Committee members said that they had worked well in concert with the 1967 Kalven Report to guide the University in its response to the campus unrest in the past year. Not all members of the University agree: In his Chronicle of Higher Education op-ed, “The Chicago Principles Are Undemocratic,” professor Anton Ford called University President Paul Alivisatos’s decision to end the encampment “a flagrant violation of freedom of expression.” Alivisatos claimed that students’ demands for divestment violated the University’s core principle of institutional neutrality, articulated in the Kalven Report.

Woodward described the report as “saying the University as a corporate entity, as an institution, has to stay well out of the way of infringing on the rights of faculty and students to express, develop and chase their ideas where they want to take them. It’s sort of the institutional neutrality that is in service of preserving free expression, which is the engine of what makes us a university.”

She recalled that the Kalven Report laid the foundation for the Principles. “A debate we had about writing the report was whether the Kalven Report had said it all,” she said.

This past spring, trustees and donors at other institutions were enraged that their presidents did not speak out more forthrightly against alleged antisemitism on campus. Those attitudes affected their philanthropy; protests last spring led to Harvard’s donations decreasing by 15 percent, according to CNN.

At the University, the Kalven Report, reinforced by the Chicago Principles, “helped forestall the demand, or that trustees [would] expect the university to make a certain position on an issue that was highly controversial and highly, highly painful,” Warren said.

“I find the Chicago way—the combination of the Chicago Principles, plus the Kalven Report—really helpful for unpredictable situations like the one we’re living,” Olinto said.

Last year, the Anti-Defamation League gave the University a failing grade on its campus antisemitism report card, calling out University leadership for their silence following Hamas’s attack on October 7. The University responded, citing the Kalven Report as the reason behind its decision not to publicly condemn the attack.

The members concurred that the Principles were never meant as a one-size-fits-all solution.

“The Chicago Principles are not a recipe. They’re not a set of instructions for what to do in any particular situation, right? It’s a statement of ideals,” Woodward said.

To that effect, in 2014, Strauss worried that the Principles would be interpreted as more of an answer than intended, which he called a “mistake.”

“When you commit yourself to the principle, you’re tempted to think, ‘Okay, I’ve solved the problem for all times and in all places.’ And, of course, you haven’t,” he said.

Beyond the University, the Principles have entered the national discourse through many channels, invoked not only at other schools but for political causes, recently cited in a Republican-backed bill encouraging all higher education institutions to adopt the them.

In certain instances, the Principles have been used in support of causes diametrically opposed to the freedom of expression the document intended to champion, Strauss said.

The report has set the stage for state legislatures to impose themselves on decisions that should be made by universities, said Warren, calling the bill a case in which the Principles are being utilized to silence voices, a line of thought that the committee drafters disagree with.

Warren called it “a grotesque irony” that Ron DeSantis was one of the earliest champions of the Chicago Principles. He called DeSantis’s changes to the university system in Florida an “encroachment on all the matters of freedom of expression.”

“So, yes. The document allows for problematic and erroneous interpretation,” Warren said.

At the time of drafting, Warren also worried that the publicity the document generated at its outset could lead to a propagandistic dogma.

“I felt it could be turned into a kind of club to beat other institutions with,” Warren said.

He worried that the report had been implemented at other universities and co-opted by the political right almost immediately after it was released; the document from the outset was upheld as a creed that institutions should adopt before the effects could be observed.

“It might have made sense five years out from the adoption of the Principles to say, ‘Well, how is it working at the University of Chicago?’ But that wasn’t the case. So people were using it to make political debaters’ points, rather than to focus on the process and how one makes freedom of expression an active value,” Warren said.

Reflecting on what was left out of the report, Warren returned to the distinction between academic freedom in a university context and freedom of speech under the First Amendment.

“I do think that a clearer description of what academic freedom entails might have been a useful addendum,” Warren said.

Academic freedom privileges certain types of speech over others, while under the First Amendment, all speech is equal before the state. The former depends on expertise and judgment— the notion, as the legal scholar Robert C. Post explained, that ‘there are true ideas and false ideas,’ and that it is the job of scholars to distinguish them,” wrote Jennifer Schuessler in the New York Times. The unsettled debate over the role of protest in a student’s education has made it unclear whether the University’s “truth-seeking mission” encompasses both definitions of speech.

Chris P. Dialynas Distinguished Service Professor of Economics Marianne Bertrand underscored the need to rearticulate the Principles’ raison d’etre.

“One weakness of the Chicago Principles might be that they don’t articulate explicitly enough why freedom of expression is so important. Is freedom of expression the objective in itself, or a tool to get us closer to the truth?” Bertrand wrote in an email to the Maroon.

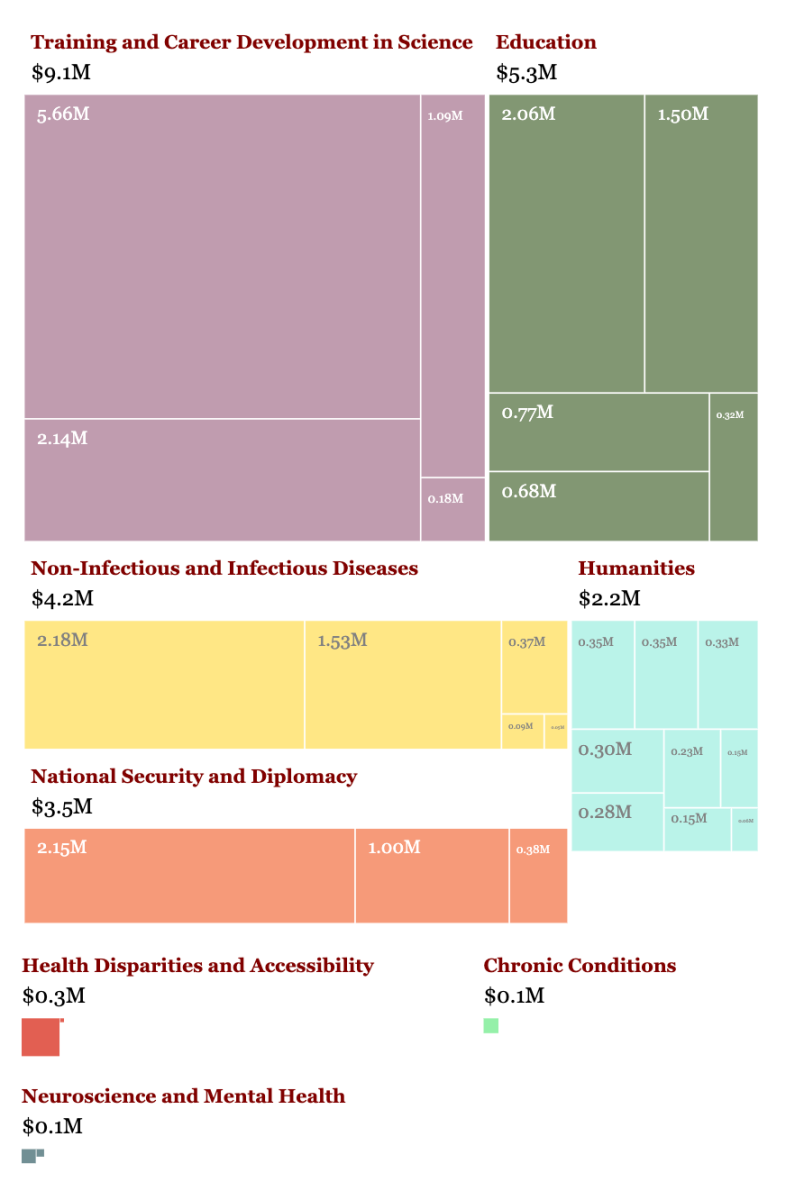

Since the initial drafting of the report, universities have become increasingly reliant on donors to fund scholarships and grants and construct new facilities. Recently, the University received $100 million to dedicate to the inaugural Forum for Free Inquiry and Expression, also called the Chicago Forum.

Some faculty point to the association of free speech principles with the University’s institutional identity as evidence of its success as a branding strategy, rather than a set of values. “The ordinary members of the university community are related to the Chicago Principles in something like the way that the employees of Procter & Gamble are related to the ‘values’ described on its corporate website,” wrote Ford in his Chronicle op-ed.

“The university has become a corporation and a hedge fund, a tax haven for billionaires, and a playground for the children of the upper middle and upper classes,” said professor Eman Abdelhadi in a panel discussion held by the Chicago Center For Contemporary Theory this past fall. The panel was one talk in a sequence called “On University Values,” in which panelists debated what they viewed as contradictions between the University’s values and its interests as an employer and investor.

“Faculty are weaker than ever before and are facing increasing austerity,” Abdelhadi said in the scathing critique.

Ford continues to criticize the report as hegemonic, arguing in his Chronicle op-ed that the document was never ratified by the faculty council or by Student Government.

At the “Chicago Principles at Ten Years” event held at the Chicago Forum, Stone refuted that claim by listing groups of people the Committee had consulted. “We met with members of the faculty across the university. We met with all the deans in the University. We met with the deans of students in the University. We met with groups of students in the University. We talked to individuals outside our institution elsewhere.”

However, Stone agreed that the corporate model universities have begun to follow in the last century generates institutional pressures.

As a result of this model, “private donors exercised a great deal of power at many universities—not Chicago—but many universities, in saying, ‘Well, you can’t teach students X, Y, and Z, because if you do that, we won’t give you money.’ What you want to tell your donors is, ‘If you value the institution, don’t do that,’” Stone said.

Looking toward the future, Bertrand raised a concern that the growing reliance on donors could inhibit the university’s ability to act freely in their role as educator.

“Ideally, the University would be even more transparent about the sources of the philanthropic support it receives, as well as support it declines because the donors’ demand might be in violation of the Principles,” Bertrand wrote in her email.

Overall, the committee felt that the document, despite its weaknesses, has served its purpose. They couldn’t have written the report without an already-established culture of free expression to guide them, they said.

Cultural preservation doesn’t happen on its own, Woodward said. The responsibility falls on the community to pass down free speech values to each next generation and keep the Principles alive.

“We have been a community of scholars since 1892, and generations of scholars have come to this place, learned what that means, and conveyed it to the next set of people who come to this place in the way that any kind of culture is conveyed from generation to generation,” Woodward said.

“My reflection 10 years later is we’re still debating them and what they mean, and that’s exactly what should be happening.”