UChicago students and faculty, alongside hundreds of researchers and activists from across Illinois, protested the Trump administration’s targeting of scientific research at a rally on Federal Plaza on March 7.

As part of the “Stand Up for Science” campaign, scientists at various U.S. universities, labs, and policy organizations planned events worldwide that day to “defend science as a public good and pillar of social, political, and economic progress.” Volunteer organizers also led major rallies in New York; Washington, D.C.; Paris; and dozens of other cities.

Since January, the Trump administration has targeted many of the normal functions of federal scientific organizations—freezing grant funding, slashing the National Institutes of Health’s (NIH) coverage of “indirect” research costs, and firing or offering buyouts to thousands of employees at federal agencies.

While many of these efforts have been blocked or temporarily stopped by courts, the future of research programs that rely on federal grants to operate—along with federally funded research in general—is in doubt.

Universities including the University of Pennsylvania, Johns Hopkins University, and Duke University have cut graduate admissions and rescinded acceptances, and Duke has put plans to build a new research center on hold.

At the Federal Plaza rally, the Maroon spoke to Rob Rodriguez, a Ph.D. candidate at the University studying protein mutations and their impact on cancer development. Rodriguez expressed concern about attacks on scientific research in the U.S., which he called “scary.” He also spoke about the impact that cuts to NIH and National Science Foundation (NSF) funding would have on his lab.

“My laboratory is funded almost exclusively by NIH and NSF grants,” Rodriguez said. “We had a grant currently in the cycle that is now kind of undetermined if it will ever leave the sort of purgatory [caused by Trump administration actions]. Doing science is inherently expensive, so in order for us to continue doing our work, we need these funding opportunities to go through, and they’re just not.”

According to Rodriguez, the lab where he works will be in a position of “financial bankruptcy” if they do not receive the grant they applied for.

The Maroon also spoke to Tom White (J.D. ’84) and Lynn White, who attended the rally with their two grandchildren. While rally-goers began chants of “out of the lab, into the streets,” the White family stood on a median between the Plaza and South Dearborn Street, waving signs at cars that drove by. The signs read, “Donald Trump stop making bad choices” and “We Love Mother Earth.”

“We support science, and we also thought it would be a good experience for our five-year-old grandkids to learn about protest,” Tom White said. “We think it’s really important for the [Trump] administration to know that a large part of the public is very upset about what’s going on.”

Organizers led the crowd in a series of chants: “When the NIH is under attack, what do we do? Stand up, fight back!” Later, rally speakers included researchers from Illinois universities, a biotech startup founder who receives NIH funding for a skin sensor used to monitor chronic conditions, and a former NSF employee fired during one of the Trump administration’s recent mass layoffs.

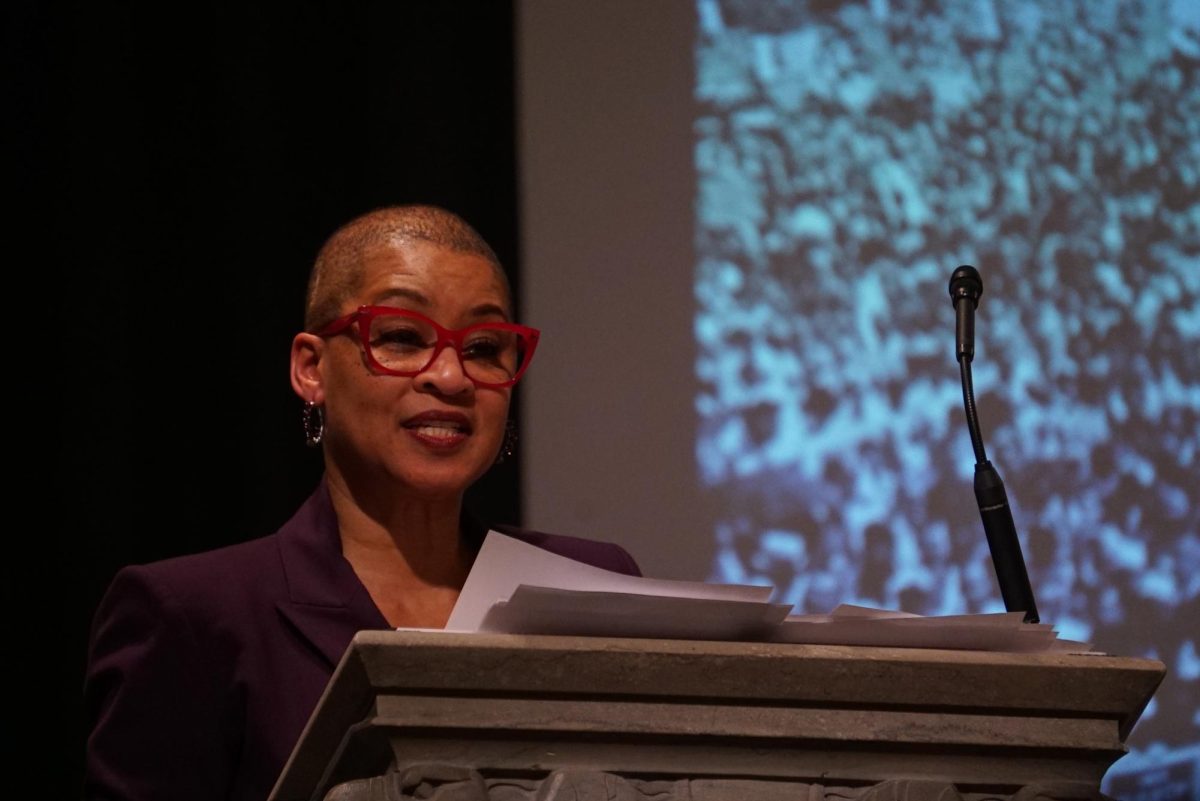

Melissa Byrn, assistant dean for clinical research at UChicago, and Luella Allen-Waller, a postdoctoral fellow in UChicago’s Department of Ecology & Evolution, also spoke.

“Without [federal research] funding, breakthroughs in medical science will slow down. Your mother’s cancer will wait for a cure. Your child’s genetic disorder will wait for a breakthrough,” Byrn said. “The research that can save lives may be delayed or may never come. So here’s where we need your help: as taxpayers, your voice, your vote, your advocacy will impact the future of scientific advancement.”

“Sometimes it’s hard to see the immediate payoff that comes from drug development in clinical trials,” she continued. “They take a long time, but when we receive a thank you note from the spouse of a patient, or we look in the eyes of a child who’s been cured because of a breakthrough therapy, the impact of clinical research is right in front of us, and it’s tangible, and this happens every day across our city and across the world.”

Allen-Waller underscored the damaging effects of funding freezes on research projects and emphasized the need for collective action.

“The White House’s severe new funding guidelines directly attack the work of me and my colleagues. Projects trying to identify strategies for resilience to climate change are now at risk, projects like indigenous land stewardship, things like protecting low-income communities that are at risk from pollution,” she said. “We love these things, and not only are they trying to defund this lifesaving science, now they want to censor the research outcomes too. Is that what we do in a democratic society?”

Senator Dick Durbin (D-Ill.), the ranking member of the Senate Judiciary Committee and a vocal opponent of Trump, also spoke at the rally, emphasizing the importance of sharing the personal stories behind scientific and medical research.

“The key to this campaign to restore funding for medical research is very basic. It comes down to six words that should be included in all of your conversations on the subject, and the six words are these: ‘Let me tell you a story,’” Durbin said.

“Tell a story about your research and the difference it makes in the lives of ordinary people. Tell your story about parents desperately waiting for that one word from a doctor, who says, ‘There is a cure. There’s research, a clinical trial you want your child to be in. We think it can help,’” he continued. “That kind of information gets down to the heart of the issue. We need to stand together for medical research.”

Following the rally, the Maroon spoke with several graduate students from the Biological Sciences Division (BSD), the University’s largest academic division. The BSD website now includes a conspicuous black and red text box directing researchers to the University’s “2025 Federal Administration Actions and Updates” page.

Mira Nicole Antonopoulos, a Ph.D. candidate in neurobiology, appreciated the University’s transparency in communication despite the frequent changes to federal policy.

“[The University doesn’t] know what’s gonna happen next, but they’ve been good about telling us, ‘We don’t know what’s going on,’ or ‘Now we know what’s going on; here’s some more information,’” Antonopoulos said. “They’ve been doing their best to analyze what’s happening in the moment and then communicate things with us, which is hard to do.”

By contrast, Luca Scharrer, a graduate student in the Department of Physics, believes the University has not shared enough information for him to determine whether they’ve responded appropriately to the evolving situation.

“Besides an email from [University President Paul Alivisatos], I don’t know exactly what the University is doing. It feels like it’s all happening behind closed doors, and we don’t really know exactly what’s going on, and that’s kind of concerning. I would like to have a little more transparency, I guess,” he said.

While Alivisatos and University Provost Katherine Baicker have communicated with faculty and some researchers regarding the White House Office of Management and Budget’s brief freeze of federal grants and loans and the University’s lawsuit against the NIH to block cuts to indirect costs of research, neither email was shared with the entire University community.

“Our whole degrees, our future careers depend on being able to complete our experiments now. So if the money goes away, then we kind of lose everything,” Antonopoulos said. “We’ve all been distressed about that. And the uncertainty too; we don’t know next week if we’ll have money or not.”

Steven Wasserman, a Ph.D. candidate in the biophysical sciences, expressed concern about the future of scientific research in the public sector.

“For those of us who want to stay doing public science, how much of an option is that? Once the cuts happen, how long will cuts last? What will be the consequences? What jobs will or won’t be available?” Wasserman said.