Upon telling other UChicago students about living in International House, otherwise known as “I-House,” one might be met with an “I’m sorry to hear that.” If not that, then a groan or expression of disbelief: “There’s no way.… So you do ‘The Walk’ every day?” Some might simply grimace and change the subject. I-House residency is treated like a diagnosis or even a prison sentence.

But, as any true I-House lover can tell you, there’s more to it than that. The building itself is beautiful, offering a variety of useful facilities and hosting countless events within its walls. It’s also one part of an international organization that is dedicated to building multinational connections between students. For many I-House residents, living in those hallowed halls is not a punishment but a genuine point of pride.

The History of I-House

In his memoir, Memoirs of Harry Edmonds, the eventual founder of I-House outlined the chance encounter that led to its conception. In 1909, Harry Edmonds, then a 26-year-old college graduate and YMCA worker, wished an offhanded “Good morning” to a Chinese student who was leaving the Columbia University Library as he was walking in.

To his surprise, the student stopped, thanked him, and remarked that it was the first time anyone had spoken to him since arriving in New York three weeks prior. Edmonds walked into the library, intent on continuing his business, only to realize the “tragedy” of what had just happened. He ran out to find the student, but he was already gone.

Edmonds told this story to his wife, prompting her to ask the question that sparked the creation of International House: “Can’t we do something about it?”

Feeling inclined to “do something about it,” Edmonds did some investigating. He searched for international students and found many around the city. He and his wife “decided to invite a small group to [their] home in the country on a Sunday afternoon,” Edmonds wrote.

These gatherings, informal at first, grew weekly to become “Sunday Suppers,” a tradition that many International Houses, including UChicago’s, continue. At the time, these were simply student gatherings that focused on “the coming together of students from many lands.” At UChicago’s I-House, the custom is maintained through two “Candle Lighting Ceremonies,” which happen at the beginning and end of the academic year, according to Michael Kulma, the associate director of programs and communications at UChicago’s International House.

“That’s where we bring together all of our fellows and all of our interns in that kind of spirit of building community,” Kulma said. “It’s an effort to bring [the] community together in the beginning of the year.”

As the number of attendees grew, the Edmonds had to rent increasingly larger spaces to accommodate them. By 1920, Edmonds became convinced that they needed a building specifically for this purpose. He searched around for suitable sponsors, all the while continuing to host students. It was by chance that, around Christmas in 1920, John D. Rockefeller Jr. gave a speech at a Sunday Supper and hosted some students at his house for a Christmas dinner.

Some time after, Rockefeller sat down with Edmonds and said, “I wish you would tell me all about your work, how it began, what you do, what your hopes and plans are.” Edmonds told him everything, and Rockefeller agreed to sponsor the building of the first International House in New York City. The building opened its doors in 1924 and was met with remarkable success, which led to the founding of an International House in Berkeley in 1930, followed by UChicago’s International House in 1932.

When they first opened, International Houses were intended to only serve graduate students, who were the ones “doing educational exchanges at the time,” said Shaun Carver, the CEO of the International House at the University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley). They didn’t even have to be affiliated with the associated university, according to a 2013 edition of the resident handbook for UChicago’s International House; it was open to any graduate or older students in the area. In fact, two of its most famous alumni, Langston Hughes and Enrico Fermi, didn’t attend UChicago.

Although International House was initially meant to be completely independent from UChicago, the University technically owned it for tax purposes, according to Denise Jorgens, the director of UChicago’s International House. However, over time, its relationship with the University shifted; it has exclusively housed UChicago undergraduates since 2016. At the time of the announcement, it was set to be that way “until the next major residence hall construction,” according to the International House website. It’s unclear if that still holds.

Programming

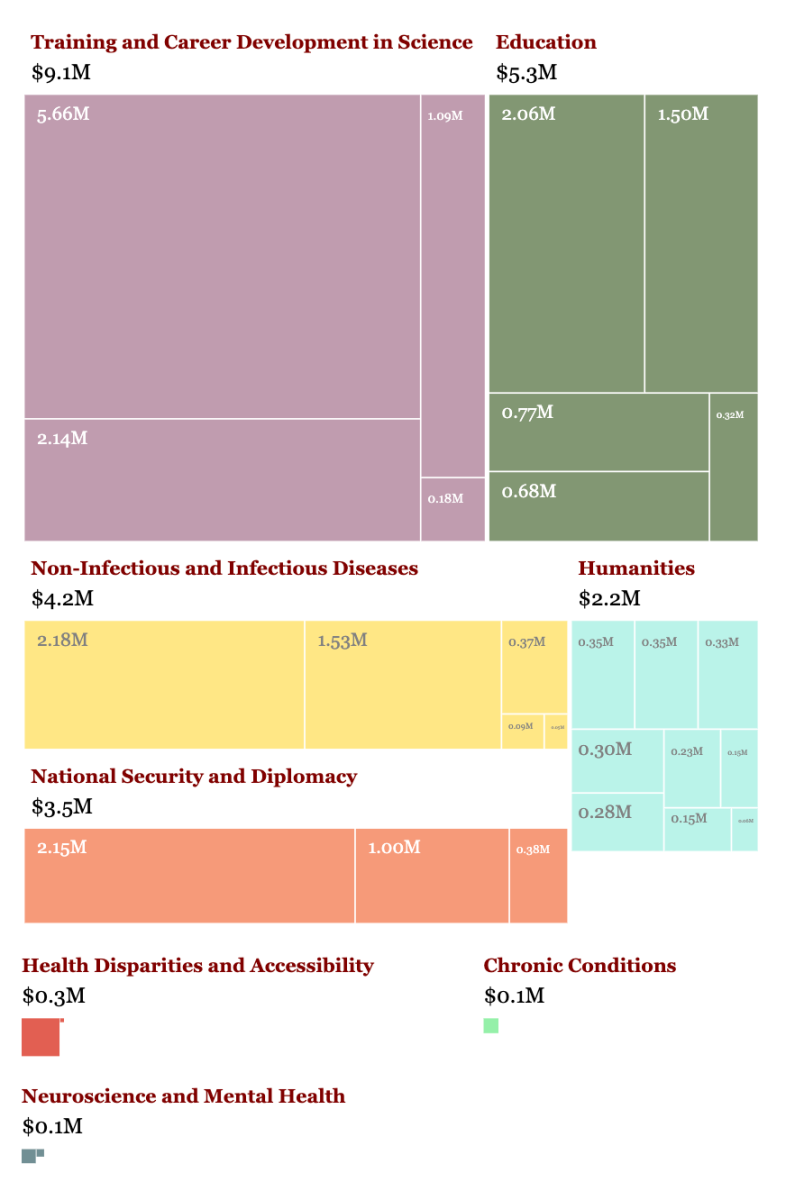

The programming at International House is split into two sections: the Global Voices Performing Arts & Lecture Series, open to the public, and the Graduate Commons Program, intended for graduate students only.

Global Voices is built on “internationally focused public programs,” Jorgens described. “We seek to engage, inspire, and steward a broad set of constituents to extend the reach of our programs… further[ing] the mission of International House, while also playing a role in the greater global conversation on important issues.” They’ve had speakers like JD Vance in 2017, Nana Akufo-Addo in 2019, Angela Davis in 2021, and Nancy Pelosi in 2015, among many others.

Kulma described the process of developing Global Voices programming as looking at “what’s going on in the world,” and trying to ideate around that. To get these speakers, he explained, International House often works with partner institutions on campus or across Chicago, like the Institute of Politics or the Logan Center. Kulma added that these partners sometimes actively “[help] to drive the content” and offer speakers and ideas to International House.

The Graduate Commons Program, on the other hand, plays a more auxiliary role in forming international bonds. The emphasis with this programming is on building connections among international graduate students through immersing them in shared spaces, with events like carillon tours and group runs as well as language tables—set up so speakers of a certain language can find each other, and those who wish to learn it can practice.

There are also many off-campus events. Within the Graduate Commons programming, there is a “Show Me Chicago” series, which focuses on exploring the city.

“You’re here as a student.… [It’s] great to get to know the place that you’re living in,” Kulma said.

International Worldwide Network

International Houses were established with the mission of creating international bonds. This has evolved into the International Houses Worldwide network, which Carver calls a “peer group.” This group meets quarterly to “[get] people’s thoughts on important topics of the time.” Their website counts 14 International Houses, though this does not include the International House of Japan or the University of Wollongong’s International House in Australia. Including the International House of Japan, the organization stretches across four continents.

According to Carver, the connection between all of them is very loose. “There’s no real agenda… or change that we’re driving at,” he explained. “It’s just a group of like-minded individuals.”

Carver then added that there’s “some sharing” of what each International House is doing about a particular topic. Kulma spoke separately about how the peer group is trying to do more virtual programming between the International Houses: “We’re all in different physical spaces. We can have greater collective impact by sitting there and saying, ‘Let’s do a program together.’”

According to Carver, there are still many differences between the International Houses. One difference he brought up between UChicago’s International House and UC Berkeley’s was in the application process. The residents at UC Berkeley’s International House apply directly to the International House and pay their room and board fees directly to International House; at UChicago, applications to live in International House are all done through Housing & Residence Life. Another difference: the International House at UC Berkeley accommodates all registered UC Berkeley students as well as visiting faculty, while UChicago’s admits only undergraduates of any year, excluding graduate students and faculty.

The process of starting an International House is so easy that it is almost surprising that more universities do not have one. Carver described it as simply as: “If you’re a university and you want to start an I-House, you can.”

“We’re working on trying to create an organization that can be the representative of I-Houses,” Carver said. This group would promote all International Houses and advertise “the benefit [they] bring to campuses.” Carver mentioned specifically that he would like to advocate for International Houses at “Harvard… [or the] University of Pennsylvania,” where they could “help bring people together.”

International Houses’ impact on the world is small but significant, according to Carver. He talked specifically about the history of the International House at UC Berkeley, detailing how it played a “big part” in ending the “very segregated” nature of Berkeley at the time of its opening in 1930. Not only was it the “first coeducational residence west of the Mississippi,” according to its history book, but it also housed students of color, and the director of UC Berkeley’s International House protested the racist policies of nearby barbers until they changed. In fact, Carver added, one of the first interracial marriages in the area was facilitated by that International House.

International House as a Dorm

“We love it,” said Craig Futterman, one of International House’s resident deans, describing the dorm. He detailed, among other things, a sense of pride over the almost 10-minute commute to the dining hall and to classes.

According to Futterman, International House has many “traditional” study breaks, like one “that’s just all imaginable junk food possible.” The love for events like these is so strong that people have apparently “pitched tents” so that they could be first in line.

He also mentioned the pride residents have for their houses, noting a “little bit of competitiveness with one another and certainly with other dorms.” The five houses that comprise International House are Booth, Breckenridge, Phoenix, Shorey, and Thompson.

Despite its relative recency in becoming a dorm exclusively for undergraduates (it began allowing undergraduates in 2010, and became exclusive to them in 2016), there was already an “existing community” by the time Futterman and his wife, Kenyatta Futterman, got there in 2016. Upon becoming the resident deans, they were immediately introduced to International House culture by the resident heads and students while also bringing a few of their own traditions and passions, like “just [having] good food.”

Craig Futterman spoke especially highly about the experience of “building [a] community, [and] really creating a space where people feel a lot of love, feel welcome.”

A love of International House has been constant throughout time. Graduate students who lived there in the past describe it as a remarkable experience. “There was so much going on,” Jennifer Milholland (A.M. ’97) remarked. “If you wanted to have something to do, you always had something… at your fingertips.”

Milholland recalled a “magical” gala she was invited to simply because she “took an interest in dancing and [was] fairly sociable.” She was “seated at this table of architects and… talking about the fact that they built some of the most famous buildings in the world.”

Anne Skove, who worked there from 1988 to 1992, also described many of the events International House had at the time: “Two or three movies a week, parties, festivals, everything. And then even smaller things [like]… a language table.”

One festival Skove remembered was the “Festival of Nations,” where everyone, including undergraduates, “had a booth from their country” that served as a place for people to showcase their different cultures. For example, she says, “the Belgians would have waffles and beer” for people to consume while walking around the venue.

Another festival Skove talked about was the Brazilian Carnaval, which she described as “city-wide, maybe more.” It was in February, and Skove recalled how it felt like “everyone in the world came to that. That was a huge party.”

There were less formal ways for International House residents to socialize, too. Michael Doherty (A.M. ’97) explained how “every Thursday night there would be just a crowd packed in the TV room watching [Seinfeld and Friends].” Milholland remembered how, during a presidential election, “there was a huge crowd of students watching the debates down in the main lounge area… and then you had people yell at the screen.”

Michael even met his wife, Natisha Doherty (A.M. ’97), while living in International House, and, according to Natisha, International House marriages were not uncommon. She described the many “I-House couples” that grew from the matchmaking hub, estimating the formation of around 10 new couples each year.

“[I-House was] kind of an intellectual incubator,” Milholland said. “I don’t know if there’s anything else at Chicago that would’ve functioned in that same way, where it would’ve been informal and cross-disciplinary.”

–

International House is a contradictory place to live. For much of the bad, there’s an equal good, at least in the view of its most loyal residents.

For the effort of “The Walk,” there’s beautiful architecture and views, much like any natural hike. For its lack of a nearby dining hall, it has Tiffin Café and countless other amenities, which make it into something of a self-contained ecosystem. This isn’t even taking into account the events hosted by International House, or its history as a global institution. It seems that, among all the bad, there’s a wealth of good in UChicago’s “worst dorm.”

Julianna / Oct 6, 2025 at 7:44 pm

No such thing as something bad with ihouse — ihome <3