President Donald Trump and his administration have set out to reshape higher education through executive orders and research funding cuts since his inauguration in January. At the University of Chicago, these policies have had visible effects on grants, campus climate, and the international student community.

Funding and Grants

The administration’s higher education agenda began with sweeping reductions to federally funded research. The loss of grants alone is expected to cost the University over $40 million in fiscal year 2026.

The majority of the rescinded funding comes from cuts to the nation’s scientific agencies. Trump directed the Department of Government Efficiency to target what it viewed as wasteful spending within the government. He also directed the Office of Management and Budget to cut programs involved with diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI), which has caused the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the National Science Foundation (NSF) to be hit with federal freezes and overall budget cuts, leading to a stoppage in grants for the University.

In response to this initial funding freeze, University Provost Katherine Baicker ordered faculty researchers to pause non-personnel spending. Although the federal and University funding freezes were reversed within a week, Baicker and Enterprise Chief Financial Officer Ivan Samstein told the Maroon in May that the University was still bracing for additional cuts.

By mid-July, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the NIH had terminated 10 University projects with an obligated total of over $9 million. This impact was especially severe in the Biological Sciences Division, which faced a loss of $1.7 million in unliquidated obligations including cuts to research related to COVID-19 and to migrants. The Arts & Humanities Division also faced the termination of 10 active grants by the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH), worth $3.1 million.

The University has been able to push back against indirect funding caps, however. In February, the NIH released a directive to cap the percentage of grants used for indirect costs to 15 percent. These indirect costs include administrative function, building maintenance, utilities, and lab equipment, and typically make up between 50 and 65 percent of grant expenditures. Lowering this percentage could have cost the University an additional $52 million annually in funding.

In response to these indirect funding cuts, UChicago, along with 15 other plaintiffs, sued HHS and the NIH, leading to Massachusetts District Court Judge Angel Kelley granting a temporary restraining order, blocking the caps in the 22 states the plaintiffs were from. This was expanded nationwide after another lawsuit that UChicago was a part of under the Association of American Medical Colleges.

The NSF had placed a similar 15 percent cap on indirect funding, placing 300 grants awarded to UChicago researchers, worth $14.5 million, at risk. The University, again, joined a coalition of universities and sued the NSF; in June, U.S. District Judge Indira Talwani sided with plaintiffs, blocking the cap.

International Students

In early April, the Office of International Affairs (OIA) learned that 10 students and new graduates— part of Optional Practical Training—had had their F-1 visas revoked for “unlawful activity,” putting them at risk for deportation.

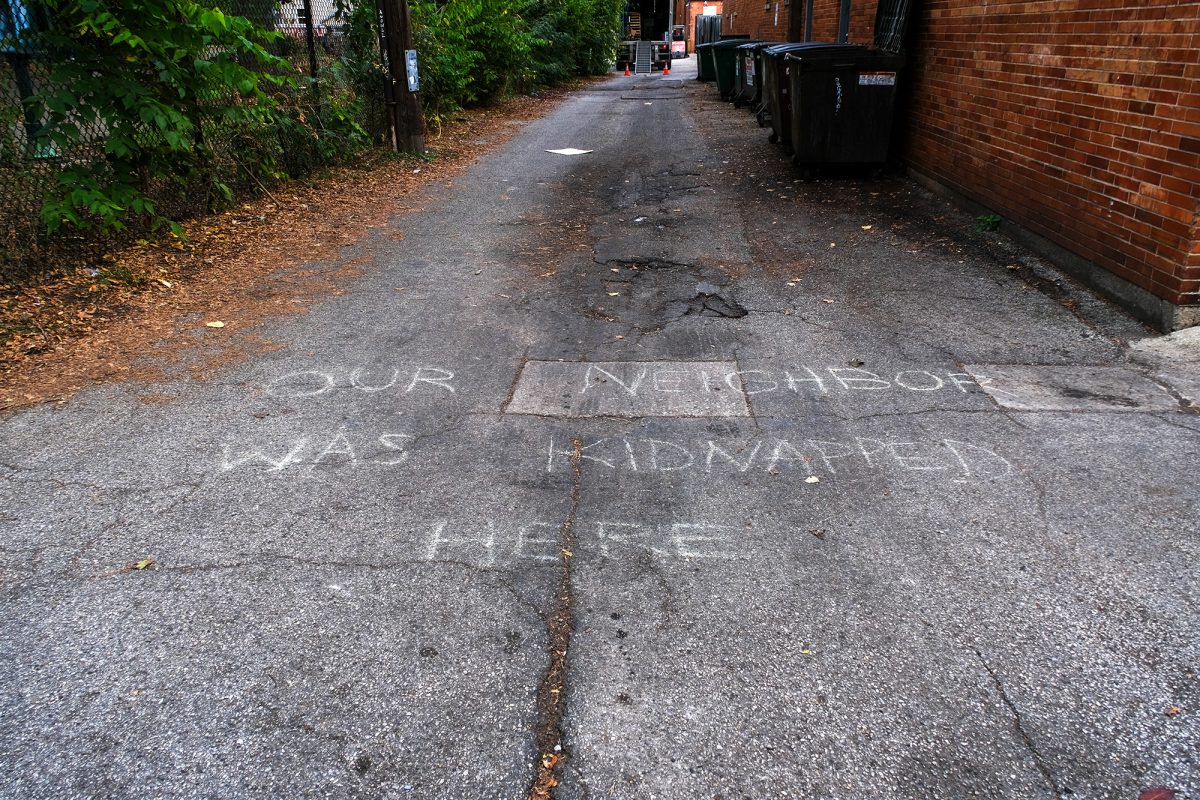

These revocations came after the Trump administration’s launch of deportation proceedings against students involved in pro-Palestine protests on college campuses. No specific reasons were given in these cases, with the Department of State citing routine border measures. The visas were restored within a month by the federal government.

The University reports that international students comprise 24 percent of the total student population.

OIA also updated its travel guidelines, urging students, regardless of citizenship status, to be cautious when travelling out of the U.S. and to reconsider nonessential travel.

In July, the University disclosed to investors via bond issuance documents that the Department of Justice (DoJ) and Department of Homeland Security (DHS) had issued information requests concerning the University’s admissions practices and international students, though the specifics remain unclear.

Student Loans

On July 4, Trump signed the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA). The legislation placed strict caps on the federal Grad PLUS student loan program, which had historically covered tuition and living costs not met by Stafford Loans for graduate students.

Under OBBBA, annual borrowing limits were also reduced to $25,000 for master’s students and $50,000 for preprofessional students, while the previous structure that allowed students to borrow up to the full cost of attendance. At UChicago, where annual graduate tuition regularly exceeds $60,000, this change will leave many students with substantial funding gaps.

Without these loans, many students are expected to turn to private loans with higher interest rates and fewer protections, or, in some cases, delay or abandon enrollment altogether. Samstein warned that a decline in graduate enrollment would significantly impact both tuition revenue and the University’s ability to maintain robust graduate-level programs.

Campus Climate

Just days after his inauguration, Trump signed an executive order, titled “Additional Measures to Combat Anti-Semitism,” instructing agencies to explore civil and criminal measures to address antisemitism on campuses, expand enforcement under civil rights and conspiracy statutes, and provide guidance to universities on grounds of inadmissibility for individuals linked to terrorist organizations. Though no actions have been taken at UChicago yet, this does put the University at risk of losing federal funding should events occur on campus that the Trump administration deems antisemitic.

In February, the Department of Education also issued new regulations claiming that the “diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programs” at many universities—including UChicago—violate the Civil Rights Act by enabling “discrimination” on the basis of race or gender; the Department of Education gave schools two weeks from the announcement to comply or risk losing federal funding.

Within a week, a federal judge in Maryland issued a preliminary injunction, blocking parts of the Trump administration’s actions targeting DEI programs, but the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit lifted the temporary injunction in March.

After the injunction was lifted, the DoJ announced that the University of Chicago was among 45 universities under investigation by the Department of Education for alleged violations of Title VI, which prohibits race-based discrimination in federally funded programs. The probe focused on the University’s partnership with the PhD Project, which aims to expand diversity in business school Ph.D. programs. The Department of Education alleged the program limits eligibility based on race, though the PhD Project has since “opened our membership application to anyone” who is interested.

UChicago confirmed it received notice of the investigation and stated it would cooperate with the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights, emphasizing its prohibition on unlawful discrimination.

The scrutiny of the University has not been limited to its academic sphere: UChicago Medicine (UCMed) has also faced pressure from the federal government. The hospital announced in July that it would discontinue all pediatric gender-affirming care, effective immediately, citing warnings from the Trump administration to withhold federal funding from hospitals that provide such services.

The hospital explained that in light of “continued federal actions,” continuing to provide such care could endanger the hospital’s ability to treat Medicare and Medicaid populations that make up over 70 percent of inpatient services at UCMed. The move follows a January executive order directing agencies to prevent federally funded institutions from providing gender-affirming care to children “under 19.”