Sculptor Lorado Taft may have just been making a statement on human morality when he installed the Fountain of Time statue on the west end of the Midway in 1922. But as it towers over the rest of Washington Park, the wizened concrete form points just as well to various incarnations of the changing park over the past 86 years.

Sculptor Lorado Taft may have just been making a statement on human morality when he installed the Fountain of Time statue on the west end of the Midway in 1922. But as it towers over the rest of Washington Park, the wizened concrete form points just as well to various incarnations of the changing park over the past 86 years.

The early 20th century’s Washington Park, for instance, featured carriage roads and grazing sheep. In the 1920s, the changing demographics of the surrounding neighborhood brought black semiprofessional baseball teams as well as frequent, racially charged brushes between youth gangs. Today the park is home to dozens of softball teams, jogging paths, and summer festivals.

But time isn’t the only thing that changes the park. Depending on whom you ask, the park can seem like one of two very different places. To some, it’s a beloved spot for pickup games and summer picnics. To others, its name elicits steer-clear warnings and snickering remarks about drug deals and prostitution.

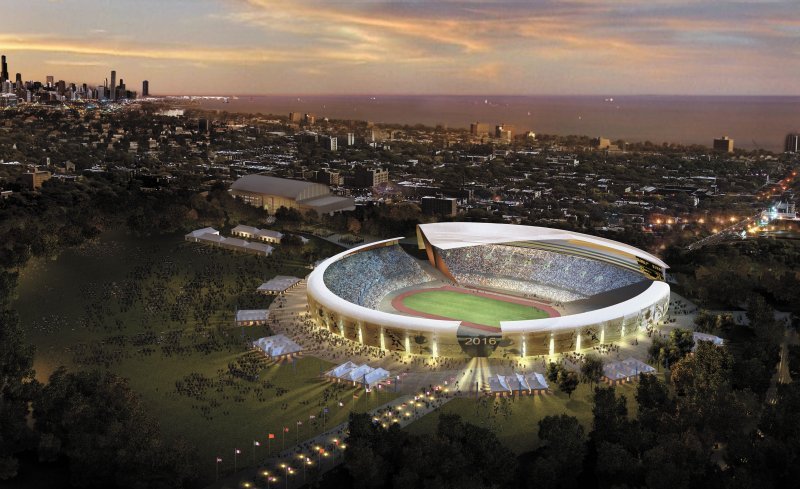

Regardless of their opinions about Washington Park, most Chicagoans would agree that the space is on the verge of its most radical transformation yet. In October 2009, the city will hear the fate of its bid to host the 2016 Summer Olympics. Chicago’s victory would call for the construction of an 80,000-seat stadium in the heart of the 372-acre park, which would be turned into a permanent 5,000-seat venue after the games’ end.

“Exciting for the University”

In a community where replacing a grocery store fuels months of emotional controversy, the Washington Park stadium proposal was never going to be a quiet affair. Since Chicago won the national bid in April of last year, local residents have held several meetings to discuss everything from traffic congestion to the pros and cons of artificial turf.

When the fate of Chicago’s bid is certain, community discussion will probably turn to a debate on the merits of various Olympic planning details. For now though, local residents can only make educated guesses about those details. The city has released concept drawings, not blueprints, of the proposed stadium in Washington Park and the Olympic Village south of McCormick Place. The website of Chicago 2016, the corporation organizing the bid, has an FAQ section that raises more questions than it answers: for instance, “our Olympic Village will turn an underserved area into a gleaming, new mixed-use community,” and “detailed plans will be available in the future.” With the future still uncertain, there are few concrete details to fight for or against.

In spite of the preliminary state of Chicago’s Olympic plans—at least the ones that have been made public—the Olympics have already elicited responses of enthusiasm and wariness from the community.

With President Robert Zimmer sitting on the Chicago 2016 Exploratory Committee, the University has high hopes for the Olympics. Associate Vice President for Communications Robert Rosenberg said the games have an obvious appeal.

“The fact is the Olympics are exciting for the University, the city, and the community,” Rosenberg said. “Very clearly, we would have a role to play with the stadium in Washington Park.”

Though nothing has been made official, plans have been made to use Ratner Athletics Center as a warm-up facility. In June the University will host the Arts Olympiad, a symposium for political and cultural leaders to discuss how to make the 2016 games both successful and characteristically “Chicago.”

Transforming the South Side?

Like many supporters in the community, Rosenberg believes the Olympics have the potential to transform the South Side’s infrastructure.

“The question is: Can we do it in a planned, community-based way that helps to transform the community in a long-lasting way?” Rosenberg said.

He acknowledged that some Olympics, including Atlanta and Los Angeles, the last two summer games held on U.S. soil, were seen as having little long-term benefit for their communities. Chicago, he says, can do better.

“I think that if this Olympics didn’t have a legacy of transforming the community—transportation, education, housing, amenities—then we will have missed an opportunity,” Rosenberg said.

Rosenberg looks at Barcelona’s 1992 games as the model for 2016. He described how after years of oppression under Francisco Franco, the games spurred the city to make much-needed improvements like cleaning up its harbor, which until then had been a virtual cesspool. In fact, Skidmore, Owings and Merrill, an architecture firm behind the Barcelona games, led the design of the master plan which won Chicago the national bid.

“It’s my job to be optimistic,” Rosenberg admitted. At the same time, he’s quite familiar with the argument that many Olympic cities, including Barcelona, lost money on the games overall.

“You could also look at it and say this was an extraordinary investment in the transformation of a great city,” he said. “And transforming the South Side is a noble and worthwhile activity.”

Along with congestion and security, the continued affordability of housing ranks high among community concerns about the Olympics. Rosenberg says the University has kept such concerns in mind with recent development projects such as the townhouse-style homes of Lake Park Crescent in North Kenwood and in condo developments on 63rd Street.

“We’ve always been very mindful of housing that’s not only affordable for community residents, but we also have faculty who can no longer afford to live in Hyde Park and want to have houses,” Rosenberg said. “We share those concerns about members of the community being able to stay in the community in good affordable housing.”

But many community members aren’t so sure, especially given the University’s notorious urban renewal program in the ’50s and ’60s. Lonnie Richardson of the affordable housing group Southsiders Together Organizing for Power feels that displacement is already alive and well in the neighborhoods surrounding Washington Park. He sees the Olympics as a threat to the already low supply of low-income housing, which he said has not been adequately addressed in his 40 years on the South Side.

“They haven’t solved those problems yet, and they’re bringing on another campaign with the Olympics,” Richardson said.

If historical trends hold, Richardson may be right to worry—especially about the housing problem. The Geneva-based human rights organization Centre on Housing Rights and Evictions estimates that two million people have been displaced by Olympic games in the last 20 years. Even in Barcelona, the availability of public housing dropped by almost 76 percent between 1986 and 1992; a report to the London General Assembly last year found that infrastructure improvements in Barcelona disproportionately benefited international residents and property investors.

According to U of C senior economics lecturer Allen Sanderson, some amount of what he calls “the bad buzzword, gentrification,” is inevitable. He is certain that some current residents will be priced out of the neighborhood if Chicago wins the bid.

Though she fears Sanderson may be right, third-year and Southside Solidarity Network member Hannah Jacoby hopes the development could bring some positive changes to the community.

“There are certain things like transit improvements, just very basic structural improvements to roads and facilities, that would certainly benefit everyone in the community,” Jacoby said. “And the issue of the food desert on the South Side—there’s the potential that Olympics would bring a proliferation of grocery stores.”

But that optimism only goes so far. Jacoby estimated that property tax hikes spurred by 2016 Olympics development could have an effect similar to that felt in Barcelona, affecting an area stretching from Roosevelt Road to Northern Indiana.

“I think the problem is the kind of development that happens around the Olympics is a really unsustainable kind, because everyone goes crazy to build things that are going to be used for a month,” she said.

Jacoby also pointed to the split in community opinion on the Olympics. Some community members, such as long-time Washington Park Advisory Council President Cecilia Butler, believe in the games’ potential to positively transform the community, according to Jacoby. Those who have long hoped for the funds to build a new conservatory and improve the park’s arboretum see the Olympics as a benefactor, Jacoby said. But others, like Richardson, fear they will be priced out of the neighborhood before such improvements are made.

“We don’t know our future, if we’re going to be here—not only in the neighborhood, but in the city,” Richardson said.

Weighing the external costs

Despite the controversy over the value of a Chicago Olympics within the Washington Park neighborhood, the city overall seems to favor the bid. A poll conducted by the Chicago 2016 Bid Committee in April found that an overwhelming 84 percent of Chicagoans support the city’s Olympic bid.

But the story might not be so simple. Economist that he is, Sanderson had his doubts about these figures. In a Chicago Tribune op-ed last month, Sanderson wondered what dollar amount citizens would put behind their support.

“I suspect that at least 84 percent of those polled were also in favor of world peace, fewer potholes, and the Cubs winning the 2008 World Series,” Sanderson wrote in the editorial. “But a more relevant way to elicit information is to face respondents with some prices or notion of the sacrifice required to achieve a stated objective.”

Sanderson anticipates more than a few such sacrifices. Assuming historical trends hold, the yet-untold billions will go to an Olympics that leaves behind few real infrastructural improvements, a clutter of demolition-ready temporary venues, and a smattering of wealthy developers and construction unions.

Washington Park will likely undergo one of the most radical changes. Sanderson predicted in an interview that the park will be unusable for at least two years during the stadium’s construction and partial demolition, putting a stop to the usual nonstop schedule of picnics and ballgames that usually characterizes summers in the park.

According to Richardson, however, the park is already beginning to fall out of community hands.

“The Olympic committee was in the park one day,” Richardson said. “Community people came to ask what they were doing. They told them to leave the park, like they didn’t have the right to be in it. They said that we were trespassing—how can we trespass on our park?”

Sanderson has his own doubts about the planning phase of the bid.

“I don’t care whether the Olympics come here or not,” Sanderson said. “What I care about is when the mayor says it’s going to cost $2 billion.… There’s no number under $10 billion that I would take seriously.”

Sanderson’s skepticism comes partly from a familiarity with what he says is the city’s habit of low-balling budget estimates. Construction on the Dan Ryan Expressway ran to twice its budget; Millennium Park, three times.

On the other hand, some amount of funding will go toward “gussying up” the neighborhood, which could translate into the kind of restaurant and retail options some Hyde Park residents have long awaited.

“The city will spend some money on making the place more beautiful, and building better housing, which will reduce the crime rate,” Sanderson said. “We’re one of those areas that will benefit—I don’t think a whole lot, but a little bit.”

But he pointed to one major short-term cost of the Olympic stadium that could be more of an equal-opportunity headache: congestion. Sanderson has already planned to evade the traffic and crowds by leaving town for the three weeks during the games.

“If I can sublet my apartment for $20,000, I could watch the Olympics on TV from Tahiti,” he said. “It’s not that I’m opposed to the idea [of the Olympics]. But the opportunity cost of my being in Hyde Park for those three weeks has got to be something like $10,000.”

Congestion and security are closely related issues with regard to the Olympics. Sanderson predicts that cars will be banned on Lake Shore Drive during the games and wonders whether car checks will be instituted if the transportation artery remains open.

Richardson and Sanderson both expressed concern that the games would give everyone from local crime lords to international terrorists over six years to make their own Olympic plans. It’s telling that security alone cost Athens $1.35 billion for the 2004 games, the first Olympics held after the September 11 attacks.

“The police department—they can’t handle the neighborhoods now, just with the people coming in and the high rate of gangs organizing,” Richardson said. “If you’re talking about the Olympics, people are going to be coming in from all over the world. How are they going to deal with that? Like on the news, you’ve got blackouts downtown, traffic jams downtown. How are they going to deal with the traffic jams here?”

Perhaps the common basis for everyone from Rosenberg’s to Sanderson’s views is a lack of certainty. While examples from Olympic history lend themselves to some sound predictions, concrete facts about future plans and effects are few. Clearly, the Olympics have the potential to make momentous transformations to the South Side—for better or worse. But it seems that community residents will have to wait for more than a year for some hard data on how their lives will change.

“Three or four people have asked me independently, from outside the University, ‘Is it just me, or is this Olympic Committee not being very forthcoming?’” Sanderson said. “And every time I said, ‘No, it’s not just you.’”