When students and faculty returned to campus after the COVID-19 pandemic, and more people were living on the south side of campus, they began to notice something: cars on the Midway weren’t stopping for pedestrians.

Since Woodlawn Residential Commons opened on 61st Street in 2020, bringing 1,298 new beds to the south side of campus, more people have been crossing Midway Plaisance on a daily basis.

“It’s 8 a.m., I’m trying to go to my class, and I’m risking my life, [almost] getting hit by a car, basically every single day,” second-year Nicholas McNamara said in an interview with the Maroon. “I’m always wondering if the car’s actually going to stop or if the car is going to hit me,” he continued. “It just always feels like I’m playing a game of chicken.”

The heightened attention to pedestrian crashes on the Midway post-pandemic coincided with an increase in traffic accidents in Chicago, as well as a national uptick in reckless driving. According to the Chicago Department of Transportation, traffic fatalities across the city peaked in 2021 over the last decade at 186 deaths, up from 120 in 2019.

However, data shows that Midway Plaisance’s dangers precede the pandemic. The number of traffic crashes—defined as a vehicle colliding with another vehicle, pedestrian, bicyclist, or another non-passenger roadway user—on Midway Plaisance was 25 in 2018 and 28 in 2019.

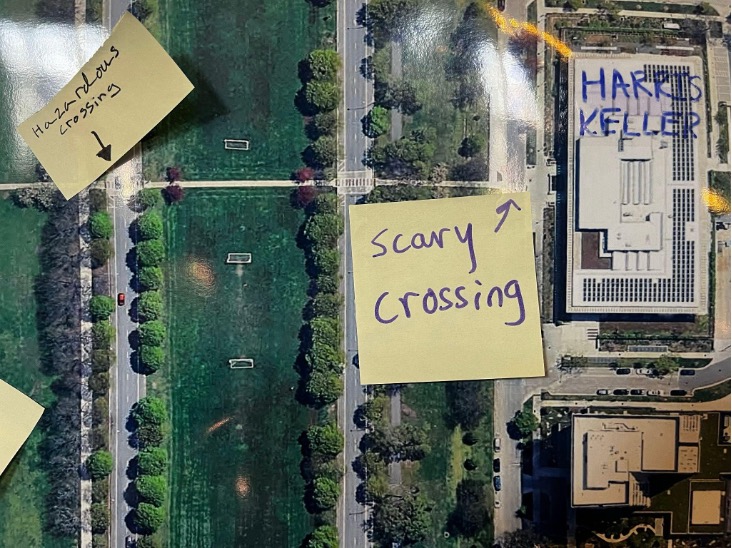

Last year, the Midway—along with 57th street, another busy two-way street—experienced the most crashes among east-west roads on campus at 15. Experts say that the Midway’s perils are a result of the road design.

“The road design signals that it is for fast traffic. It has the classic signs of a limited-access highway,” Kavi Bhalla, an associate professor in the Department of Public Health Sciences at the University of Chicago, told the Maroon. “You’ve got only two lanes moving in the same direction, and, as you look ahead, you see an open road with no congestion.”

Bhalla said that policymakers often prioritize easy transit for cars without as much consideration for cyclists and pedestrians. “We do live in a world where people who control transportation are biased toward moving cars fast, and not toward walking and bicycling.”

Karlyn Gorski, an assistant instructional professor in the Harris School of Public Policy who teaches a course on transportation, told the Maroon that there is more to pedestrian safety than what the accident data captures.

“It’s not just that I haven’t been in a crash that matters, but also how many times I have to go sprinting across an intersection because vehicles aren’t slowing, or how many times I have to just stand around at a crosswalk, especially on Midway Plaisance, because drivers don’t stop for me even though they’re supposed to,” she said. “The stuff that’s more difficult to see in quantitative data like this is what makes up so much more of the experience.”

In the spring of 2023, the city installed raised crosswalks on Midway Plaisance, intended to slow down vehicle speeds and improve pedestrian visibility. Bhalla cites that information in a study he conducted to evaluate pedestrian safety on the Midway reviewed by the Maroon. However, Bhalla found that the crosswalks are not high enough to be effective.

When he measured car speeds on the Midway at the elevated crosswalks closest to the Harris School of Public Policy and the Logan Center on November 11, 2023, he found that one-third of cars exceeded the 25 miles per hour speed limit by more than 10 miles per hour before approaching the crosswalk. On average, cars drove through the elevated crosswalks at 32 miles per hour. Studies find that pedestrian impact with a car driving at 30 miles per hour results in significantly higher risk of severe injuries than those hit by a car at 25 miles per hour.

Concerns about pedestrian safety eventually led 65 faculty and staff members to write a letter to President Paul Alivisatos and Provost Katherine Baicker in June 2024.

The letter said that current efforts by the administration were “limited to piecemeal, remedial, low-budget improvements such as painted crosswalks and tree trimming.”

A new plan “would demonstrate the University’s stated commitments to community and civic engagement, safety and security, public health, and sustainability through greenhouse gas reductions,” the letter read. “Further, co-designed solutions would allow for collaborations between faculty, staff, and students.”

What followed was a vague response and no follow-up, according to Emily Talen, co-signee of the letter and a professor of Urbanism in the Social Sciences Divison at the University of Chicago. “I sent a follow-up six months later,” she said. “That one didn’t get any response.”

The University did not comment when asked about its response to the letter.

Students and faculty members have pointed out a pattern of minimal university engagement with students and faculty and a lack of transparency regarding the University’s policies.

In April, a group of students and faculty members held an event called “Transforming Mobility: A Summit on Campus Transportation.” In response to their requests for more engagement from the University, Assistant Vice President for Campus Planning and Sustainability Alicia Berg, who attended the summit, said that the lack of partnership was due to the University’s fiscal challenges.

“Incremental steps is kind of the approach we can achieve right now, given the fiscal realities of the institution,” Berg said.

However, given the University’s influence and relationship with the city, Gorski said that it can advocate for changes in the South Side neighborhood, such as having more raised crosswalks, curb bump-outs, and well-maintained sidewalks.

In fact, in 2000, the University and the Chicago Park District developed “The Midway Plaisance Master Plan.” The aim was to transform Midway Plaisance into a community amenity and a connector between the north and south sides of the University campus.

One of the visions laid out was to change Midway Plaisance “from expressway to ‘stroll’ way.” The plan from more than two decades ago arrives at a similar diagnosis as present day: the biggest concern about Midway Plaisance for community members is the high volume and speed of traffic.

It identifies solutions such as pedestrian lighting, bulb-outs, distinctive paving at crosswalks and even closing traffic entirely on weekends to create a “pedestrian-friendly zone,” which has yet to be attempted.

“I just think that it’s such a missed opportunity that this vision has been around for decades, but real change has not come. Just to continue to have this car-centric [street] feels like a scar on what could be beautiful park space and public infrastructure,” Gorski said.

Students and faculty at the University also say that there needs to be a more comprehensive approach to mobility that addresses issues such as walkability, bikeability and access to public transit.

“Why do so many people drive to campus? Why isn’t there better attention paid to traffic demand management?” Talen said. “We started realizing a lot of campuses do mobility plans, especially if they say they’re focused on sustainability.”

Talen considers the Oregon State University’s (OSU) campus plan to be the “gold standard,” because it ties together different types of transportation and incorporates input from students and staff, as well as community members outside the school.

According to its “Sustainable Transportation Strategy,” OSU aims to reduce drive-alone commute trips by 20 percent by 2030 by implementing different strategies, including working with the city to expand public transit service to campus and providing more connections between campus shuttle routes and local transit stops.

While UChicago has not released a public plan regarding mobility and transportation, it responded to an email from the Maroon with planned improvements on the Midway.

To improve pedestrian safety, the University said, in correspondence with the Maroon, that it has been working with the city to add yellow flashing crosswalk lights, speed feedback signs, painted areas with bollards and concrete bump-outs—a traffic calming design where sidewalks are extended into the road to make it easier for drivers to see pedestrians.

Although bump-outs encourage drivers to slow down, students and faculty have previously raised concerns that the current level of parking along Midway Plaisance may limit the effect of bump-outs on pedestrian visibility.

“I feel like there’s a lot of ambiguity in the relationship between the campus administration and the student body, because they’re not very transparent,” McNamara said. “[University officials] need to be better at communicating with the student body [about] what they’re doing and how the student body could affect that.”

BSD Employee / Nov 6, 2025 at 7:26 pm

Any traffic control devices on the streets have to be approved by the City of Chicago.

We need a little more advocacy and involvement on this issue.

Videos of traffic ignoring workers and students in the mornings and the evenings would go a long way to demonstrating the need.

On the Drexel crossing the Midway, there are bases for some kind of devices at the crossings, but nothing has been installed yet.

C Peterson / Nov 2, 2025 at 10:01 am

As a local motorist I can attest that the crosswalks (and waiting walkers) are not particularly attention-getting from the driver’s seat. I would welcome pedestrian operated flashing lights — even red ones.

Josh Kurutz / Nov 2, 2025 at 9:55 am

Has this plan included adding a flashing-light crosswalk and matching curbcuts to cross Ellis Ave. at Searle? Hundreds of people every day cross between the main Searle entrance (where there is no curb cut and no loading zone) to the walkway between Kersten and Hinds (where there *is* a curbcut and a loading zone). This is a safety hazard for everyone crossing. Further the lack of a curbcut at Searle makes it virtually inaccessible to wheelchair and walker users. Moreover, freight is often handled at the Searle curb without a loading zone, resulting in trucks blocking the street, and heavy, delicate scientific equipment being roughly handled to get it from each truck to the sidewalk. This crossing definitely needs attention.