Audre Lorde draws a distinction in “Uses of the Erotic” that any adapter of great love stories should keep in mind. The erotic is “the chaos of our strongest feelings.” Real feeling demands something from us. Pornography, for Lorde, is a far cry from that feeling, merely sensation without emotion. The body is engaged while the self stays safely uninvolved. Did Emerald Fennell read Lorde before adapting Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights? Based on the picture itself, probably not.

Instead of a faithful adaptation, Fennell says that she’s after something else, to evoke “the most physical emotional connection” she felt reading Emily Brontë’s novel at 14. Fennell has her signature move: undercutting every earnest moment with the kind of winking self-awareness that worked in Promising Young Woman and Saltburn. The thing is, Wuthering Heights doesn’t survive Fennell’s signature treatment.

The film opens with plenty of promise: Owen Cooper as young Heathcliff and Charlotte Mellington as young Cathy deliver the only performances that land. Cooper and Mellington bring depth and realism to the story, investing the audience in their friendship and adventures. Whatever emotional connection to the characters the audience manages to scrape together rests entirely on these two kids.

The mise-en-scène is obviously beautiful. Shot in Yorkshire Dales National Park, the film’s jaw-dropping imagery sometimes reads less as narrative cinema and more as a tourism ad for Northern England. Cinematographer Linus Sandgren’s location work is one of the few aspects grounding the audience in reality, though “grounding” feels wrong for landscape shots that seem designed for social media.

Then comes Jacqueline Durran’s costume design. Among the best in the business, with two Oscar wins and nine nominations, her work on Little Women, Pride & Prejudice, and Anna Karenina established her ability to craft period dresses that carry the ambitious tasks of emotional period dramas. Here she immerses the audience in corsets, lace, and velvet. She draws from Victorian high fashion, German milkmaids, vintage Chanel, and the Golden Age of Hollywood. The mise-en-scène does at least half the film’s emotional work, often outperforming the actors.

Fennel described the film as an “imaginative exercise” in recalling her first encounter with Brontë, trying to invoke that initial response for audiences. Wuthering Heights emerges from this desired emotional connection crossed with Fennell’s signature subversive pastiche. What if we could make a period drama that acknowledges its own artifice while still moving us? In theory, this sounds promising.

In practice, the picture is a tonal catastrophe. The melodrama is overshadowed by the irony of Fennell, never quite tugging at the heartstrings like great love stories do. Fennell abandons the promising throughline of childhood friendship, opting instead for a hypersexualized progression of the same connection. Some might be tempted to call it miscasting. However, the problem goes deeper.

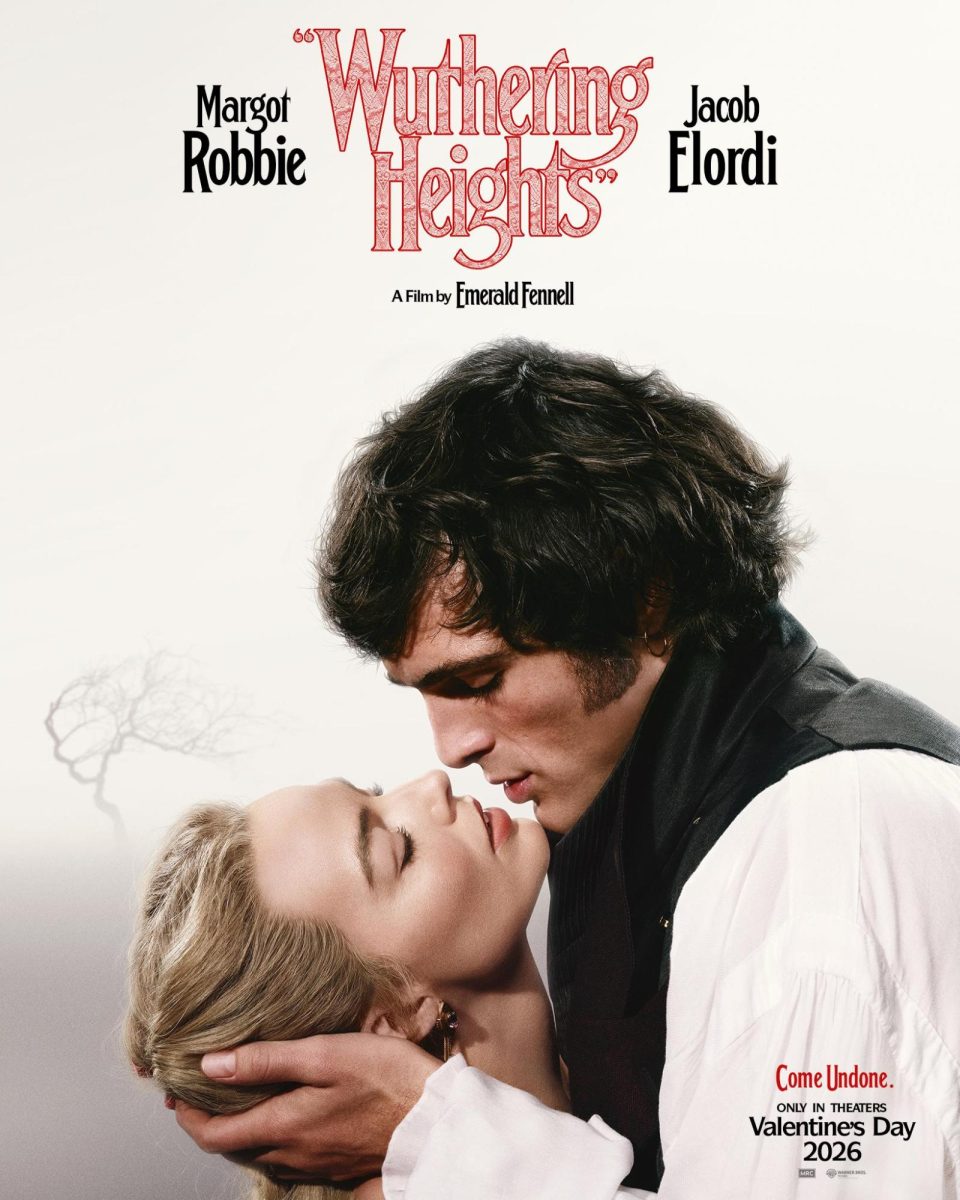

Margot Robbie and Jacob Elordi, two beautiful people whose combined star power could light up a small city-state, are the main draw for popular audiences. Everyone wants to watch Robbie and Elordi smolder at each other across windswept moors. Yet, Fennell doesn’t seem to have asked whether this casting serves the material or just the audience’s desire to see attractive people be attractive together. There’s a word for this: pornography. It’s in Lorde’s essay.

Despite the physical beauty of landscape, the exquisite shot composition, and two gorgeous film stars, none of this is the erotic in Lorde’s sense. Wuthering Heights feels like smutty fanfiction written with the sole narrative goal of engineering scenarios that place Elordi and Robbie alone on screen with the constant thrill of potential discovery. The picture is a hollow replica, a merely pornographic substitute for the original novel. Lorde writes that “the erotic is not a question only of what we do; it is a question of how acutely and fully we can feel in the doing.” A film can be gorgeous and leave us cold. Such beauty without feeling is nothing more than expensive wallpaper.

What has kept readers returning to Wuthering Heights for nearly two centuries is an emotional connection to characters that are fully alive in their suffering, desire, and rage. The film barely hints at the broader themes of class, gender, and racial commentary in which the original text found its success. Fennell’s film offers no such depth. Her renditions of Catherine and Heathcliff never face such external conflicts or threaten to dissolve into each other, because the two are barely fleshed out as individuals.

The audience finishes Wuthering Heights not moved, not interestingly unsettled, but rather, vaguely embarrassed. Fennell mistakes aesthetic sophistication for emotional complexity. Lorde would recognize this immediately, a pornographic impulse dressed in period costume. The actors are beautiful. The landscape is beautiful. The costumes are beautiful. Everything is beautiful, except the one thing that matters: the feeling itself.