When I left high school this past June, it was in shambles. Amid teachers being put on administrative leave for voicing their opinions and a head of school unwilling to address the Israel-Hamas war, one issue that seemed to fly under the radar was students’ use of artificial intelligence (AI) technology in the classroom. Teachers had widely differing policies when it came to the use of large language models (LLMs) in written work. Some strongly advocated using ChatGPT for research and idea generation, while others scorned the very concept of AI. At points, it felt like I could walk into the cafeteria and see dozens of people prompting ChatGPT for help with their homework. While the school added a small paragraph in the student handbook about integrity and AI, limits on its use remained unclear and were ineffective at stopping students willing to bend the rules. More than just policy, it seemed that there was no place to critically interrogate the future of LLMs and their implications for higher education. By my senior year, I had written multiple articles about the future of machine learning and writing, but it felt like I was shouting into a void that garnered no conversation in return. Besides a few lame attempts by the school to engage students on AI, the topics seemed to have gotten overshadowed by the more pressing issues facing the school.

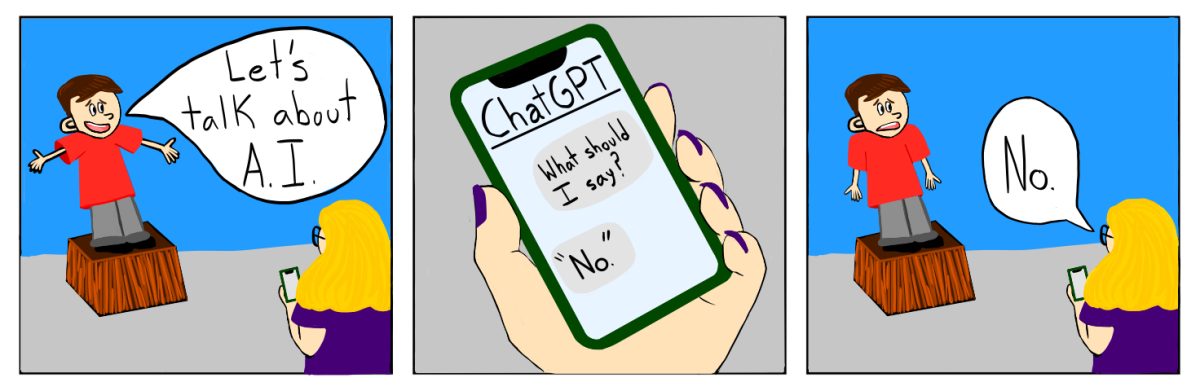

When I arrived at UChicago, I expected a similar indifference to the topic that I was so interested in. This assumption was almost immediately proven wrong when my Language and the Human professor, Tomasz Zyglewicz, emailed our class and attached Ted Chiang’s New Yorker article on ChatGPT. Looking back, it seems absurd that I didn’t expect large language models to come up in a class about linguistics, but my high school experience made it seem like that was the status quo. Then, when it came to walking into that first class, I was not exactly sure what to expect from my professor vis-à-vis AI, specifically ChatGPT. Would he immediately condemn its usage, citing its rampant hallucinations, bland writing style, and over-repetition of certain words like “delve” and “moreover?” Would he embrace it as the future of all things written, advocating for us to prompt it every time we needed? While the first option seemed far more probable than the second, neither made me happy.

What I experienced instead I can only describe as chiefly, “UChicago-y.” After going over the course material and syllabus, Tomasz wrote the words “AGAINST,” “NEUTRAL,” and “FOR” on the chalkboard. He explained that instead of dictating the AI policy himself, he wanted to hear students’ opinions on using AI in our writing. I was pleasantly surprised, as none of my previous teachers had ever consulted us in this way, so I raised my hand almost immediately to respond to his prompt. I’ve always had strong opinions when it comes to AI, and I wasn’t afraid to share them. I hold the belief that there is no point in fully banning the use of AI, as students will always find a way to use it if they are truly motivated to cheat, as I had seen in high school. While ChatGPT doesn’t live up to my standard of academic writing, it is enough for some people to get by on their work. In true UChicago fashion, there was a great diversity of thought on the topic, with some in favor of banning it on principle and others wanting it to be fully allowed. But one main thread that seemed to be echoed by pretty much everyone was the importance of original, and human thought. One person spoke up, saying, “You can use ChatGPT to write your paper, but then you know that you are writing a C-level paper.” Unlike high school where writing was usually treated with a level of apathy, I felt that my classmates cared about the quality of their arguments. No one directly advocated for using ChatGPT to replace writing altogether.

As I write this piece, OpenAI has just released their new ‘ChatGPT Pro’ subscription, costing avid AI users $200 a month to have unlimited access to their newest model, ‘o1 Pro.’ While OpenAI spent plenty of time in its launch video touting o1 Pro’s incredible reasoning and writing capabilities, I am left wondering if it has the ability to write essays with the same level of precision as a motivated student. I would be lying if I said that I never put essay prompts into ChatGPT to see what theses or groundbreaking arguments it could come up with. And every time, I would end up wasting time prompting ChatGPT more and more to try and get at the ideas that I felt were the most important—time I could have spent writing the thing myself. In the end, I always feel a bit dissatisfied with ChatGPT. As Chiang wrote about, it seems that having access to every corner of the internet makes your writing a bit bland, like you don’t care. In my classmate’s words, it writes a “C-level paper.” That’s not to say ChatGPT doesn’t have a place in academia as a tool. Its new ‘search the web’ feature has proven invaluable to me for finding sources, or finding that one sentence in a book that I lost. But its value in writing high-level pieces is overhyped. Until LLMs like ChatGPT, Claude, and Gemini can achieve genuine intellectual nuance and develop a more discerning voice, I will remain skeptical that it can truly exceed the capabilities of a thoughtful, motivated student.

In the end, we settled on AI being permitted with citations, and I left feeling excited at the level of enthusiasm surrounding the conversation on AI and pedagogy. While it seems obvious that UChicago would attract students who enjoy learning and the process of fleshing out their thoughts in words, I still felt a sense of pride in the fact that at the very least, my Hum class believed in our own reasoning skills over a computer’s. Are there people who will buy ChatGPT o1 Pro and use it on their assignments? Undoubtedly there will be, but I hope not at UChicago. And, while I still have over 11 quarters of UChicago to go, this first one gives me hope that I will continue to have enlightening conversations about the future of AI, teaching, and learning.

Adam Zaidi is a first-year in the College.

Angelo / Feb 11, 2025 at 9:14 am

Pay no attention to the hater(s)—they have posted the same tired comments in response to other students’ opinion pieces. It’s probably the same loser posting the same criticism under different names. This piece was extremely well written and enjoyable. Keep up the good work!

You can do better / Jan 18, 2025 at 10:12 am

Good ideas, terrible execution.

JJ / Jan 15, 2025 at 6:45 am

…indeed, this piece falls into the common trap of so many youthful attempts at commentary: it mistakes verbosity for insight and outrage for depth.

Not meaningless, not meaningful. Just nothing. Not worthy of publication.

The Maroon would do well to consider a writing workshop for its contributors. One would (naively) expect that UChicago students would produce thoughtful, well-crafted work. A pity that is not the case.

JJ / Jan 15, 2025 at 6:30 am

“I”, “me,” and “we” in every paragraph. Personal biography, no real issue analysis.