Although economics at the U of C today is all about models and regressions, it used to be all in the roll of the dice.

In a recent New York Times article, technology editor Damon Darlin (A.B. ’79) mourned the new electronic version of Monopoly and advocated for the Monopoly he used to play. For Darlin, Monopoly wasn’t just about learning to make correct change. It was a game of strategy and rule-bending, a case study in free-market capitalism at the height of Milton Friedman’s tenure.

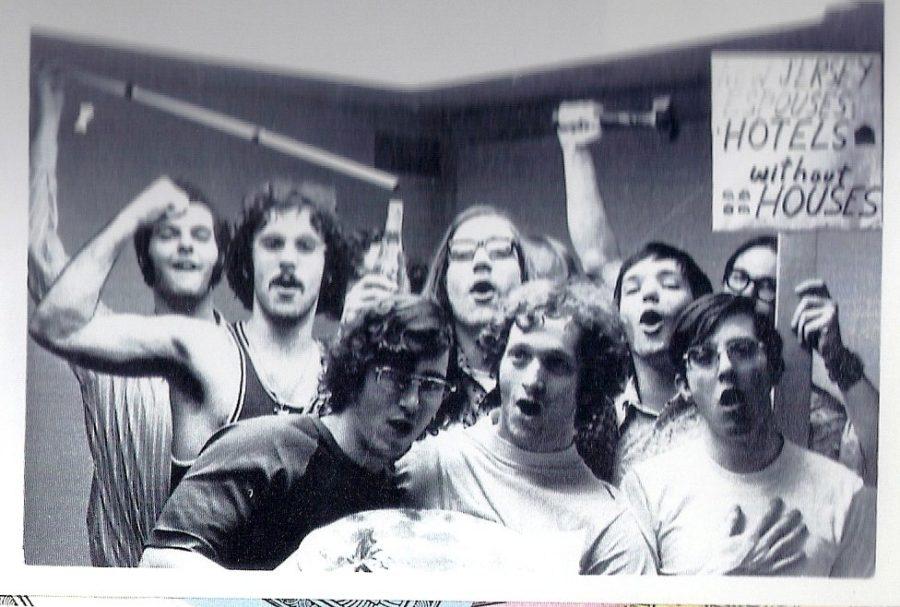

In the ’70s, in fact, Monopoly seized the residents of Shorey House, who lived on the ninth and tenth floors of Pierce Tower. Darlin, an American history concentrator, remembers U of C students of the late 1970s playing Monopoly every weekend and discussing free-market capitalism with Milton Friedman himself.

An interior study room of Pierce Tower became “The Monopoly Room” in the fall of 1973, said Ed Conner (A.B. ’76, M.B.A. ’78), a player and founder who concentrated in history and is now a corporate lawyer.

Conner remembered group of students rolled dice, bought property, and consumed pizza starting at 10 p.m. several times a week, playing a couple of short games each night.

“The games were pretty serious. By the end of the year, the game board, money, deeds, etc. had taken quite a bit of physical abuse, in no small part due to the nearly constant exposure to pizza grease. During my tenure, we were strict constructionists when it came to the Rules of Monopoly—rules which we considered immutable and sacred,” Conner wrote in an e-mail.

Shorey’s monopoly obsession spanned years. After Conner moved out of the dorms, economics concentrator and former Maroon staffer Mike Zelenty (A.B. ’77) called for a “constitutional convention,” where he challenged the existing rules of the game and created new ones.

All of Shorey House, said Zelenty, vied for the title of Monopoly Champion, a title measured with a token system. He credits the board game with creating a cohesive house community.

“It’s rare to have something so many people focus on for hours in college, people with different majors and interests. A single simple board game brought us together,” he said. But of all the members of the house, there were four to five regular players who “were the ones shouting at two in the morning about railroads,” he said.

The group expanded to eight regular players and opted for longer weekend games and alcohol over pizza (this was back in the day, when the drinking age was 19 for beer and wine). “The Monopoly fanatics were eclectic, but there were also these free-market types, usually econ majors or in business school. They’d invite Milton Friedman to sherry hours,” Darlin said.

Shorey House’s snack bar Tanstaafl, standing for Friedman’s favorite expression “There ain’t no such thing as a free lunch,” typically hosted Friedman and his wife twice a year. The Friedmans sipped sherry with students for an hour or so each visit.

“He would talk economics with the students. They would get heated fast, but he was so nice about it, so politic as he disarmed their arguments,” said Darlin.

It was during these informal sherry hours that Zelenty asked Friedman to sign his board. Friedman wrote “Down with” above the game’s name. Though both the Regenstein library and Chapman University, which owns a Milton Friedman collection, have contacted Zelenty about the board, he has not decided whether to donate the board or pass it on to his daughter Jennifer, a third-year physics major at the U of C.

Zelenty rarely plays Monopoly now, though he admitted he enjoyed beating his children at the game when they were younger. “They didn’t take long to figure it out. They used to gang up on me. It’s fun to negotiate properties and trick people and then laugh. It’s fun to take vengeance. I can’t imagine playing the new board. The idea of a computer telling you how to play is just opposite the very idea of the game.”

Darlin’s article recounts his most memorable game, when rule changing and self-minting reflected the very principles of economics. “Who won has long been forgotten, but it was one of the greatest games of Monopoly ever played because we got to change the rules,” Darlin wrote.

Rule changing, said Darlin, is something the U of C helped teach him. “Question all of the assumptions was a big part of the education here. It’s the only way to get progress,” he said.

“I guess a lesson learned is that facts are facts. There are cheap people and people who really go for Park Avenue and the dark blues. But playing emotions doesn’t work out. It’s nice to think a light blue or purple monopoly will work but orange is the strongest,” said Zelenty, who admits he still favors the light blue and purple properties.

Conner upheld Zelenty’s argument about the orange properties. “One of the more important things I learned in my four years at the U of C was that ownership of all four railroads and control of the orange properties was almost always a winning combination. That knowledge alone was worth the price of tuition,” said Conner.

But, as perhaps it was destined to, the game lost its monopoly on Shorey House and was replaced by a foosball machine by Darlin’s third year.

Still, tradition dies hard, and it’s unlikely that U of C students will ever stop learning from the games they play in their free time. As a Class of 2014 essay prompt warned potential applicants, “From game theory to Ultimate Frisbee to the great Chicago Scavenger Hunt, we at the University of Chicago take games seriously.”