In October, the University announced a series of changes to disciplinary procedure regarding sexual offense cases in response to suggestions from a committee formed last spring to review the existing policy.

Announced in an e-mail last month, the changes work toward clarifying the process for complainants to bring forth sexual assault cases, as well as improving sensitivity and clarifying rights once the cases have begun.

The changes, instituted over the summer, are the first modification to the sexual violation policy since 2007, when student complaints compelled the University to establish an official sexual assault policy offering avenues through which students can find help.

The revised policy states that disciplinary committees must consist of students and faculty members from several departments and schools.

This measure addresses the concerns of the Working Group on Sexual Assault Policy (WGSAP), which advocated for the past two years that the administration address problems of bias and inefficiency in sexual assault disciplinary committees.

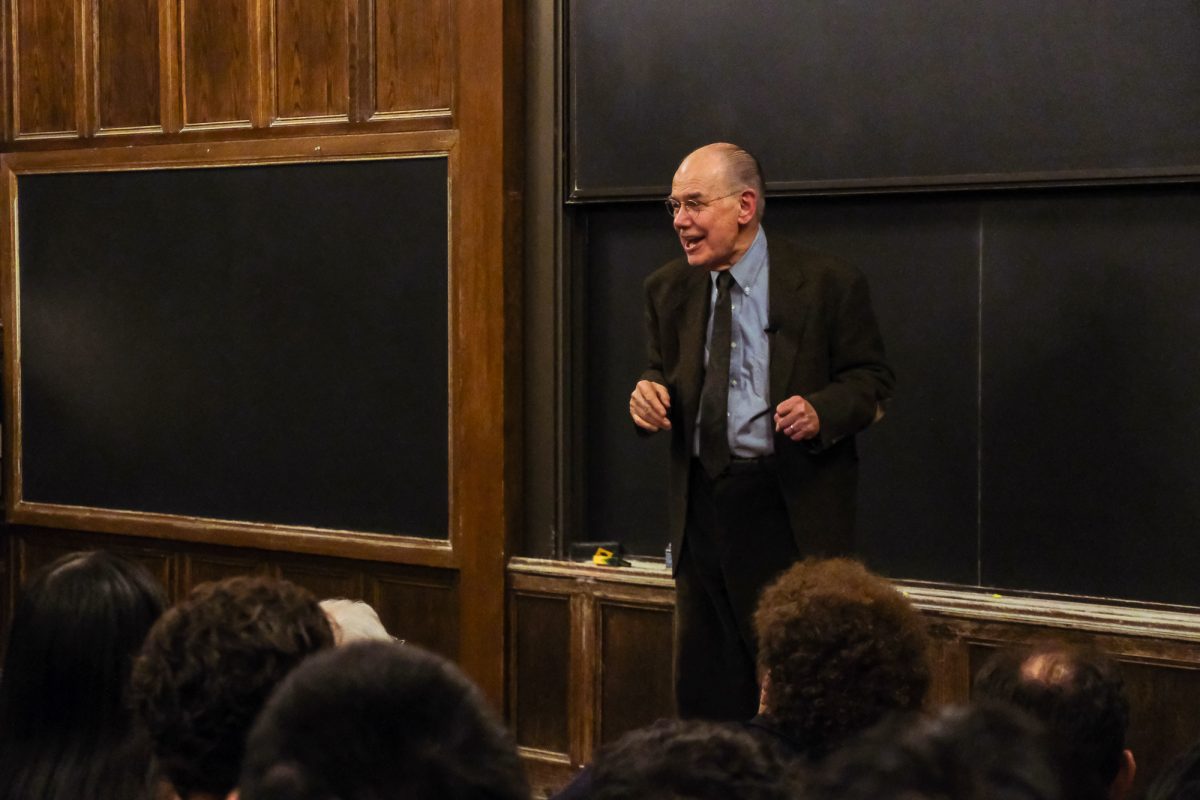

“The fact that [cases are] not 100 percent exclusively within the unit [of the accused] anymore was probably most indicative of big change,” said Kevin Cherry, WGSAP’s student representative on the committee that drafted and submitted the final recommendations to University Provost Thomas Rosenbaum.

Another important change is in tone. While the previous policy focused on the rights and responsibilities of the accused, the new policy explicitly acknowledges that, like the accused, the accuser also has rights and responsibilities.

The accuser is now entitled to see the written testimony of the accused and witnesses, permitting that the author gives consent. Nevertheless, Vice President of Campus Life Kimberly Goff-Crews added that the accused has a level of discretion and right-to-privacy in this matter.

“As I understand it, the accused student really has to give permission for some things to be distributed… for privacy rights,” Goff-Crews said. “There is an effort to at least have the complainant be apprised of what information is available.”

The reforms offer a clear codification of what the accuser—i.e. the alleged victim of sexual offense—can expect from the case’s proceedings.

“The Dean of Students will explain the disciplinary procedures to the accused student and a representative of the Office of Campus and Student Life will explain these procedures to the complainant,” reads the Student Life and Conduct section of the Student Manual, which was updated with the new policy.

Sexual assault policy reform has been a topic of discussion for the past two years, since WGSAP formed as a result of the controversial handling of a sexual assault complaint. An alumna accused a graduate student of sexually assaulting her before she graduated. In the three months before her case was heard, the University misled her about her legal options, she said, and the disciplinary committee that heard the case–made up of faculty in the graduate student’s department–was unsympathetic.

But Goff-Crews said disciplinary processes more broadly tend to focus on the rights and responsibilities of the accused. “If you think about disciplinary process in general, it’s really focused around providing the accused a very specific set of rights and responsibilities within that process,” she said.

Under the new policy, she added, “it’s clear that there’s someone who’s responsible for working with the accused student and there’s someone who’s also responsible for working with the complainant.”

Most of the changes were agreed upon in a special committee convened by Provost Rosenbaum in spring quarter, following a WGSAP-led referendum in which almost 80 percent of the student body voted in favor of reevaluating disciplinary procedure in sexual assault cases.

WGSAP had taken special umbrage with the fact that sexual assault disciplinary committees were similar to that of academic integrity violations. This complaint was addressed spring quarter when it became mandatory for committee members to undergo sensitivity training, educating members on facts about sexual assault, including that a victim might not immediately report being attacked, and other reactions victims might have.

Cherry said the administration has pledged that in five years another committee will convene to review the policy, but he said he was generally satisfied with the changes.

“It’s really just a matter of figuring out a way to maintain the energy and the interest in the issues so that people don’t forget them,” Cherry said.