This week marked the 40th anniversary of a three-day sit-in at the University, in which 450 students shut down the Administration Building to protest the University’s Vietnam War draft policy.

The protest, which took place May 12 through 14, 1966, marked the culmination of nearly three months of growing concerns over new government standards in the draft for the Vietnam War. The Selective Service summoned colleges and universities nationwide to release the grade point averages and class ranks of its students in an effort to classify academic performance for draft eligibility.

Under the previous policy, college students were eligible for deferments until they completed their degree requirements or turned 24 years old. The Selective Service proposal, however, revoked deferments from students in the bottom half of their class and made them eligible for the draft.

Public outcry over the Selective Service’s new policy swept college campuses across the nation. Students organized protests and faculty members debated the morality of issuing low grades to students who could consequently be sent to war.

At the University of Chicago, students and faculty undertook what Maroon writer Mike Seidman referred to as the “anti-grade movement” in his February 25, 1966 article “Anti-Grade Feeling Mounts.” According to Seidman, the new policy sparked both student and faculty pressure to abolish grades in the College.

“I’m not in favor of the University becoming an arm of the Selective Service,” said Richard Flacks, assistant professor of sociology, in the article. “To the extent that I have the freedom not to cooperate with the draft, I will do so.”

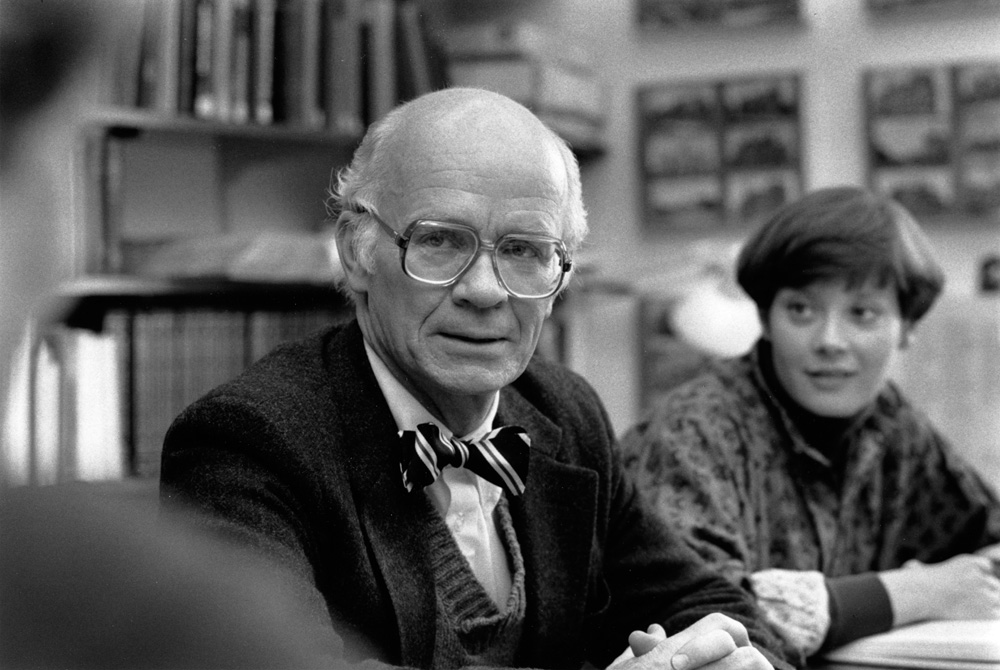

Dean of the College Wayne C. Booth called grading a “wild and inaccurate system at best,” which “perverts the true value of learning” in the article. He added that “the draft serves to dramatize the non-educational uses this device is put to.”

According to Seidman, Booth cautioned that students who did not submit their grades could be seen as “covering up” and that the draft board might single them out for selection.

Seidman wrote in April 1966 that some University professors were “disturbed” by the notion of submitting grades to Selective Service. “We are actively cooperating in a war effort whose purposes we profoundly oppose,” read a statement from professors.

Tensions reached new heights when the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), a national student activist group, organized the sit-in protest that would shut down the University’s Administration Building from May 12 through 14.

According to Kirkpatrick Sale, a contributing editor of The Nation and author of the 1973 book SDS: Ten Years Towards a Revolution, the U of C protest was “the classic confrontation” of the new draft policy.

“For the first time in its history, SDS, at the University of Chicago, went up directly against a university administration in open confrontation,” Sale wrote in his book. “SDS had successfully taken over the administration building of a major university, it had taken direct action without any punishment, and it had publicized its cause beyond anything imaginable by other, less dramatic, methods.”

While tensions between students and the administration remained high after the protest, the University did not discipline those involved in the sit-in. In 1967, the administration decided that it would not disclose class ranks and grades to the Selective Service.

The U of C protests prompted similar sit-in movements at the University of California-–Berkeley later in 1966, and by 1968, it was the main form of protest on at least 65 campuses, according to Sale.

“The realization of complicity on the part of the University, combined with a realization of how readily it could be confronted, was a crucial element in helping to turn attention back to the campus during the rest of the year,” Sale wrote.