Experts watching as H1N1 swine flu tears around the world have drawn endless parallels to the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic, which killed at least half a million people in America alone. The U of C’s flu preparations indicate that institutions have not forgotten the traumatic events of that year. But is the comparison valid? And what happened to Chicago in 1918?

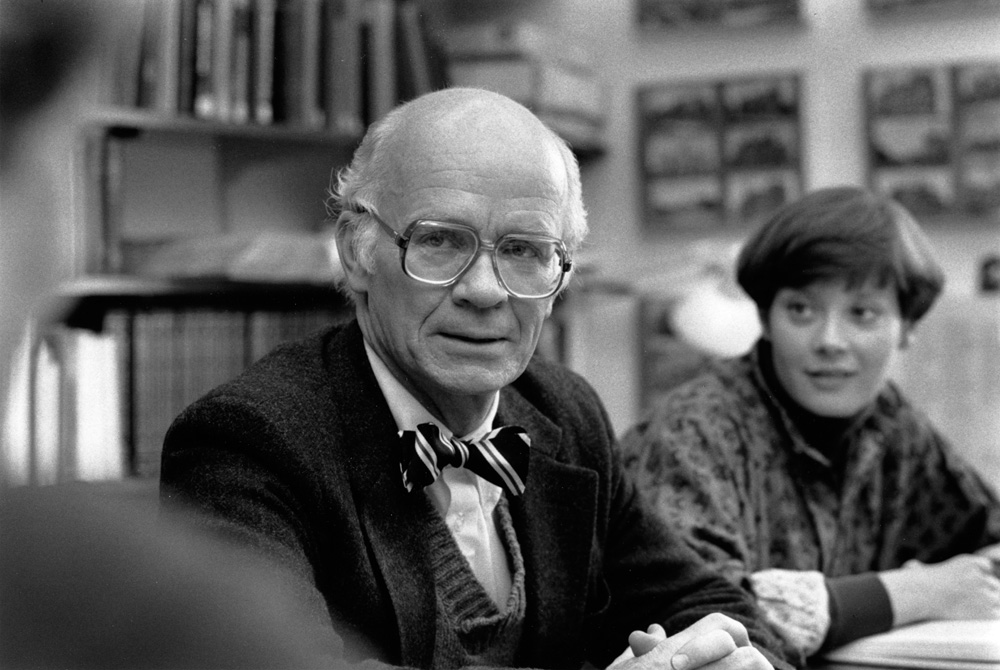

Dr. Michael David, a fellow at the U of C’s Section of Infectious Diseases, knows at least some of the answers due to his studies of the Spanish flu’s path as it blitzed Chicago over three grim weeks of September and October of 1918.

By 1918 the world was in the thick of World War I, and ships and trains full of soldiers toured the globe. No one knows exactly where the virus originated, but in August, influenza exploded across the globe almost simultaneously in three ports, located in France, Sierra Leone, and Boston. Successive waves sent the disease deeper into America, hopping across the country via military bases.

That year, Chicago’s population was about 2.7 million. About thirty miles north of the city stood the Great Lakes Naval Air Station. The flu arrived at the station on September 18, and eight days later the camp had 8,500 sick men on its hands.

“That’s how it worked. It came in little rips and then went away,” David said.

Meanwhile, on September 21, the first flu cases appeared in Evanston and Wilmette.

The flu ripped through Chicago. At the peak of the wave, almost 400 people died in a single day. 200 new cases were diagnosed daily. Beds lay empty in hospitals whose nurses had all caught the flu. City administrators shut down skate rinks, theaters, and dance halls.

“Most people died between one and 10 days after diagnosis,” David said. “It doesn’t give you much time.” Opportunistic diseases like pneumonia and staph A like to piggyback along with flu. Many deaths were probably the result of superinfections by these and other bugs.

At the time, the University of Chicago had agreed to host World War I soldiers for military training. Almost 1,000 arrived on campus just before the height of the outbreak, in two shifts. David has found sepia photographs of hundreds of soldiers assembled in front of Haskell Hall, hauling cannons across the Midway and running drills on the Quads.

Just three soldiers from the first shift were sick on arrival, and each was housed in a different building. In the next 18 days, almost half of the soldiers came down with the flu.

As they had elsewhere in Chicago, authorities reacted quickly. By the time the next batch of soldiers arrived, administrators held educational sessions and demanded that any man with symptoms report them immediately. Far fewer soldiers fell sick, and none died.

By November, reports of new cases in Chicago died to a trickle. All in all, at least 8,500 people died of the flu in Chicago, and 51,000 cases of flu and pneumonia had been reported.

“It’s likely there were thousands more,” David said. Sickness and death in poor districts, like the meatpacking district, were probably underreported.

Over half of the deaths were in men and women ages 10 to 40, creating an abnormal spike in the age of death at a time when infants less than a year old generally accounted for the vast majority of deaths.

Later studies have suggested that the virus may have activated what’s called a cytokine storm in the bodies of its victims. Cytokines are signaling molecules that mediate immune responses. A virus might trigger an overload of cytokines, sending the immune system into overdrive and damaging the body’s own cells. Healthy young adults, with strong immune responses, would fare worse than the young and elderly, who tend to have weaker immune systems.

Early reports from Mexico appear to confirm that young adults were disproportionately stricken by the flu. The data is spotty though, and no one has a concrete estimate of the actual mortality rate of the new virus. The 1918 pandemic flu only had a death rate of about 3 percent, but it infected millions of people. And U.S. H1N1 cases have been mild so far.

While modern medical advances such as vaccines, antibiotics, and ventilators could significantly reduce mortality, David said swine flu could cause other problems.

The Center for Disease Control estimates that a severe pandemic could drive 1.4 million into U.S. hospital intensive care units, or about 300 people per hospital. That burden, atop the routine caseload of patients with heart disease and other illnesses, could overwhelm the system.

Pandemics can result from a phenomenon called an antigenic shift, David said. “For example, a pig who has a pig virus also gets infected by a human virus. In the same cells, some of the genetic material gets scrambled and produces a new virus—one that can infect humans.”

Since the combination is new, most people’s immune systems don’t recognize it. If the virus can move easily from person to person, like the current virus does, it can cause serious damage.

“That hardly ever happens,” David said.

Hardly ever—but at the same time, by many accounts the world is overdue for a flu pandemic. Smaller epidemics occurred in 1957 and 1968, but they were milder and mostly affected the very young and old.