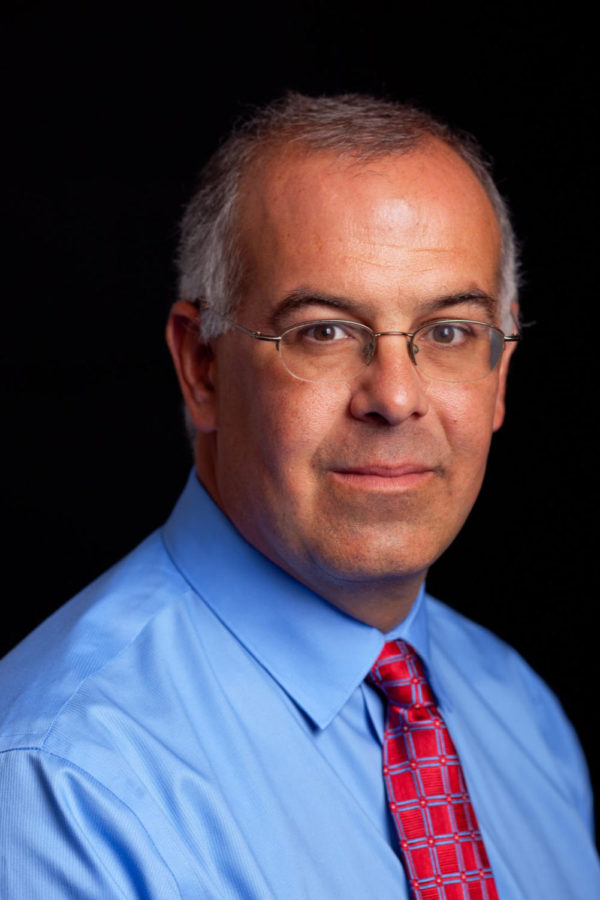

Columnist David Brooks (A.B. ’83) is a staple of the New York Times op-ed page now, but back in his college days he edited and wrote for the Viewpoints section of this paper. In July, Brooks sat down with the Maroon in his office in the Times’ Washington Bureau for an extensive conversation on his best campus memories, his relationship with President Obama, and Harold’s Chicken Shack.

Chicago Maroon (CM): What are your best classroom memories at Chicago?

David Brooks (DB): I remember the Common Core; I remember the first two years. I took a class called Political Order and Change—it was basically Locke, Hobbes, that sort of political stuff. And then Human Being and Citizen—more the humanities side. I recall my professors both smoking in those days, one of them a pipe, which is probably not allowed anymore. I remember those classroom discussions. Later in my career, I sat in on some Allan Bloom classes, and while I wasn’t a student of Allan Bloom, I was sort of fascinated by the phenomenon. I recall in the beginning of the term, all of the students looked normal; by the end, Bloom smoked Marlboros, he wore white shirts and clunky black shoes, and by the end they were all smoking Marlboros, wearing white shirts and clunky black shoes. They had joined the cult.

CM: Do you remember the feeling of being in class at Chicago?

DB: The best phrase is a Philip Roth phrase: “seminar baboon.” There was a lot of chest thumping of what you knew. It was sort of intellectual, pretentious one-upsmanship, but earnest wrestling. We were pretty serious about it. We were caught up in the whole mission of the place.

CM: You’ve mentioned that reading Burke’s Reflections on the French Revolution was the most formative academic experience for you….

DB: Yeah, that was in Western Civ, so my second year. I was taught it and I hated the book; I completely despised it. Here was a guy saying, “Don’t think for yourself, follow tradition, don’t trust your reason,” and I hated all of that. I wrote a bunch of papers condemning Burke, wondering why we were reading this guy. Gradually over the next five to seven years I actually came to agree with him—my visceral hatred was because he touched something I didn’t like or know about myself.

CM: What led you to that point? Intellectual development? Personal development?

DB: A lot of what Burke does is epistemological modesty—we don’t know much about the world, and it’s too complicated. Right after Chicago, I worked for about a year as a bartender at the Quad Club, failing as a freelance writer. During that period, and then I worked at a weekly that’s now defunct, called The Chicago Journal, and then the city news bureau, for about a year. I covered crime. I was around the Cabrini Green and the Robert Taylor homes—the big projects. Here was a living example of people who thought they could do social planning or social engineering, and it failing. That led to obvious Burkean conclusions that organic society is too complicated to plan. A lot of that led me back to Burke.

CM: Do you remember particular professors who influenced you more than others?

DB: My B.A. adviser is still alive, though emeritus—a guy named Neil Harris. I really enjoyed him. He taught about the power of culture and technology, so that was instrumental. I had William McNeill, who’s a great historian. I had a writing professor who died last year, Richard Stern, who was sort of a Saul Bellow–type writer—what they call a writer’s writer. Really it was the Core classes I had. One guy who’s still there—Josef Stern, and he taught my Common Core humanities. I vividly remember all those people, mostly for all the usual UChicago intellectual seriousness.

CM:Why did you decide to become a history major?

DB: I was totally unrealistic, so I remember one spring break in my third year, I walked around Manhattan, where I was spending my break, and I decided that if I liked Greenwich Village better, I was going to become an English major, because that was sort of artsy fartsy. I decided if I liked the Upper East Side better, I should do history since that was practical. I don’t why I thought history was practical, but I did, compared to everything else I was doing. I must have decided I liked the Upper East Side, or maybe the Upper West Side, better. So I majored in history.

CM: Did you sense a fundamental difference between what you were doing as a history student as opposed to what you would have done as a literature student?

DB: It seemed like I was preparing for this type of job, or politics, or law. My senior paper—what I did was I went to the library, I looked at all the archives, and I started with the letter “A,” and I figured I would write about the first person who looked interesting, so I got up to “Ar,” to Robert Ardrey, whose papers had never been looked at. He was a left-wing playwright in the ’30s, and then became sort of an early Darwinian theorist in the ’60s and ’70s. So I wrote about him. I’m probably the only person to ever look at the Robert Ardrey papers at the Reg.

CM: Do you have memories of studying in the Reg?

DB: Oh yes. I was a fourth floor guy, back in the stacks. There’s a coffee shop now at the lobby level; there used to be one down at the A- or B-level, and I spent many, many hours there. I had one sort of weird experience there reading Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy—it was one of those moments when you realize you’ve been reading for three hours, and you don’t realize how much time has passed, since his prose style is sort of hypnotic. That was a weird, transcendent moment, and a little scary since it was Nietzsche.

CM: How do you think the Core and your time at Chicago affects your current thinking?

DB: If you read my column, I’m constantly quoting these people. They’re just the normal people I quote. Even in writing about current events, it seems natural to me to go back to Burke or people like that. Those seem to me the sources. It frees you from the ever-more-superficial influences of the modern media; it gives you a little depth to go back to, and so when you write something you hopefully won’t forget it. It won’t be irrelevant a week later.

CM: Is that a natural process for you, or do you find yourself forcing writers and thinkers like Burke into your perspective?

DB: I think it’s natural. I’ll get a topic—even something like the Iraq War—and I’ll go back to the books I have around this office or around the house, and I’ll just stack them up and go through them and see if they spark any thoughts at all. So I will still go back and look at the Great Books, not because they directly apply, but because they stimulate ways of thinking.

CM: Stanley Fish wrote a column in May in The New York Times about getting rid of all his books. Why do you believe it’s worthwhile to keep them?

DB: I was appalled by that, mostly because you go back and re-read them, and you read them differently, because you’re at a different stage of your life. I mark in all my books so I can go back and find what I thought was an important passage, or what seemed important. I think, like most people, I can’t remember the name of the person I met yesterday. But I remember where on the page a certain passage was—I know sort of top left a little, and from years ago…. I think if you lose all that—all that work you’ve put into reading the books and marginalizing and notes and underlining—to me all that goes from your brain.

CM: Do you ever regret your first reading of something?

DB: Yeah. I still have books I read my first year, and I look at my notes. Sometimes they’re not bad because I just wrote down what the professor said. Sometimes they’re utterly ridiculous, very pretentious.

CM: Where does being opinionated come from?

DB: I think it’s genetic. Some people just are curious, but they don’t come to conclusions. Some people come to conclusions that can then be trained with an education. And then what you have to do is remember that you’re not going to have the last opinion. Your opinion may be stupid, but you’re going to throw it out into the public world.

CM: But doesn’t the Core often teach you to think outside of your own opinions, your own reactions? Is there a process that you go through as an opinion writer that distances you from a more natural intellectual or cognitive process?

DB: I have to have an opinion, and I’m not a naturally opinionated person. What I do is I marinate myself in anything relevant to the subject I’m writing about and hope something occurs to me. It’s more a process of really marinating and taking notes and talking to people about it and just waiting for something that seems interesting.

CM: How does the traditional academic philosophy at Chicago fit into the national discussion on higher education right now?

DB: I’m a little dubious of a lot of the new trends. I’m not dismissive of online education, but I’m not persuaded, at least for the people going into a four-year education, that it’s the answer. I do think that the seminar experience is the answer, and the online can supplement that, but it’s never going to replace it. As for the other stuff—obviously the decline in the humanities affects it, but I guess my view of Chicago…Chicago has become such a hot school in part because it has a distinct and serious reputation. There’s still going to be a large number of people who don’t want the more assembly line style of higher ed that’s going on. They want something distinctive, and they want something that will leave a mark, that will really change the way people are.

CM: Do you think that model is at risk because of how popular Chicago is getting?

DB: A little. I look at the admissions statistics, and they’re pretty sensational and we’re all happy about them, but when I went there—70 percent of the people who applied got in. I was not in the top half of my high school class, so I couldn’t have gotten in to most places. I certainly couldn’t have gotten close to Chicago today. I worry, and I’ve talked to the admissions people a lot about this, and I’m always asking, “Are we just going to admit the same sort of student that everyone else is admitting?” They’re reasonably persuasive that Chicago will not, and I do think the Chicago atmosphere takes people and turns them into Chicago people pretty quickly. Just being around campus, I’m persuaded that it’s still a pretty unique place.

CM: How do you maintain self-selection as the school becomes more popular?

DB: The Where Fun Goes to Die image is still out there, whether it’s true or not, so it scares away a certain sort of person. The reputation is still out there, and everything the school puts out—these thick books for recruiting—it’s still reasonably distinctive. The architecture is the same. When you visit the campus…I’m teaching at Yale and it’s different: The students in the Ivy League are more professional; they’re more transfixed by the consultants.

CM: What do you make of the information revolution?

DB: Data can do a lot for you, but it can’t do everything. The key is to understand what it can’t do. There are certain things data will never be able to do: if you’re choosing a marriage partner with data, I would really recommend against that. If you’re reading a novel with data…the data is so impressive that the people who trust it want it to do everything, and I’m a little dubious about how it can do everything. The key is to find out where the lines should be drawn.

CM: Is part of that response the lesson of the humanities?

DB: Yes. My problem with the way the humanities were taught is that they were taught as if they were social documents to do social protest and social reform, rather than inner documents for inner improvement. I blame some of the humanities professors for giving up on what the humanities are really best at.

CM: What do you think of Dean Boyer?

DB: I think he’s a treasure. It’s amazing that he was there then; he’s there now. He’s sort of the institutional integrity of the college experience. Just to be around him—you’re reminded of what it’s all about. He’s a pretty good guardian. The financial pressure still pushes us in the other direction, and even the geography of campus has changed so much.

CM: How does the campus affect the college experience?

DB: I’ve been on campus several times a year, but my wife—whom I met there—had a 30th reunion, and there were a lot of people who hadn’t been on campus since 1984 or 1985. A lot of them were appalled—they were like, “It’s just this big, global institution now.” Whereas when we were there, it felt small. Now you have that big health building sort of overshadowing the Reg—that whole side of campus…that arts building south of the Midway. To them it just looked like another big global university, and so they were shocked. But I think we had to go in that direction.

CM: But what place does the campus have at an institution like UChicago?

DB: It’s in theory a place to gather. When I was there we didn’t do any gathering. At least we were walking past each other. I do think the campus has a huge effect on the culture of the place.

CM: So what’s your best social memory from being a student at Chicago?

DB: Jimmy’s. I spent a lot of time at Jimmy’s with many different people, many different friends, girlfriends. I was there two or three months ago and it’s still the same.

CM: Does UChicago teach you the significance of solitude?

DB: We spent a lot of time alone. It’s different now. It was a pretty antisocial place in the early ’80s. Now there’s many more student groups—much more of that stuff. Student groups were not an important part of life; it was pretty much friendship and classes. Now it’s much more student life-oriented.

CM: How did Chicago inform your teaching methods at Yale last semester?

DB: I still believe in the Great Books with almost religious fervor. When I went to Yale, I’m still teaching Augustine; I’m still teaching Burke; I’m teaching the stuff I had. I think those books have the magic key on how to live.

CM: You write a lot about social science, but I know literature has affected you greatly. How does it influence your current thinking?

DB: It widens your repertoire of understanding human nature. You understand how people interact; you get certain phrases to stick in your head. I’m reading Middlemarch right now, and Eliot’s ability to define and judge character is pretty astronomical. We might say somebody’s honest, somebody’s brave; George Eliot has categories that are super fine distinctions on how to describe someone’s character. That only comes from a lot of reading, combined with actual observation.

CM: Who are some other novelists who have affected you like that?

DB: When I was in school I was a big Philip Roth guy, then a Bellow guy. Those were Chicago people. I also got deeply into Dreiser. When I moved to Europe for The Wall Street Journal, I did a lot more Russians—I read Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Turgenev. What I like to read are people who are writing about not small internal stuff, but bigger political stuff. I went through a big Trollope phase because he writes well about politics in a way that’s pretty accurate to me. The thing that frustrated me about Chicago was that there were very few faculty who had any work outside the university. Now there are more, so the novelists I read now—I want them to know something about the world outside their own heads.

CM: Do you consider yourself to be a public intellectual?

DB: No. I’m a newspaper columnist. People use that phrase, but any real academic would look down on me. I don’t want to say I’m one of those people.

CM: What do you think a public intellectual is?

DB: Edward Said was a public intellectual. In some way Bellow was. Allan Bloom certainly was. Somebody deeply rooted in some pretty serious academic field, an actual discipline, who’s still engaging in public controversy. I might qualify at the bottom of the rung. I’d want someone who has a deeper academic training.

CM: What’s the divide between public intellectualism and journalism?

DB: I have to write twice a week, so we have to churn out a lot more stuff. I cover actual events, and I talk to actual presidents and people like that. I would defend that as a superior way to get information, rather than just sitting. Sometimes I’ll go to a campus and be on a panel discussion with some faculty, and sometimes the things they say are smart—if you didn’t actually talk to the newsmakers. They’ll have smart opinions about Obama from a distance, but if you’ve spent a lot of time with him in private, then you know that’s not how he thinks. They’ll give you theories that are plausible but not right.

CM: You know the President well. How does he think?

DB: Like a writer. He’s a very writerly personality, a little aloof, exasperated. He’s calm.

CM: What distinguishes President Obama as an intellectual, or as someone who tries to elevate himself above the typical level of discourse?

DB: He’s not addicted to people. President Clinton was, Bush was. Others need to be loved; President Obama doesn’t need to be loved. He’s calmer. He’s got some things that are typical among politicians—he’s hyper-competitive. He’s more exasperated than anyone of that sort within the normal process of politics. I think he wishes he could skip it all to get on with decision-making, and discussing things.

CM: Is intellectualism unhelpful in modern politics?

DB: No, as long as you can do the other stuff. You really can’t get high in public life if you don’t have some practical, political sense, and the willingness to get your ideas across to regular Americans.

CM: Judging from your recent writing I’m guessing you don’t think President Obama has done that well enough….

DB: I don’t think he’s integrated himself with people in Washington as much as he should have. He’s fine with people like me, but we’re more like him than some of the members of Congress even in his own party.

CM: How much time have you spent with him?

DB: Since he became president I’ve probably met with him 25, 30 times. They’re off-the-record meetings with some regularity.

CM: Do you think President Obama and the group around him have suffered from the insiderness of Washington?

DB: No, not as much as they could have. They’re still aloof from it. If you want to govern in a capital city you have to know the capital. I don’t fault them for that. I think it’s suffered because he came in with a bunch of flamboyant, intellectually dynamic personalities like Rahm Emanuel, like Larry Summers and Austan Goolsbee. They’ve evolved toward less flamboyant but more team-oriented personalities. They function better as a team now. There’s less intellectual electricity than there used to be.

CM: Do you think that’s part of a data-driven approach that’s become more fashionable?

DB: A bit, and Obama wants to control it more, so he just wants people who will be team-oriented and carry out what he wants. I think he does that to a fault. I’d ask him to get a few more people who are willing to pick fights. To be fair—on foreign policy, he did just name two people—Susan Rice and Samantha Power—who are that sort of person. They’re willing to pick an argument. On the domestic side, they’re now functioning as a pretty well-oiled machine, but that means there’s less novel thinking going on.

CM: Do you think the demands of the presidency take a toll on him as a thinker? Is it harder for him to be restrained?

DB: I forget who said it, but when you’re in office you’re not learning anything; you’re just spending down your intellectual capital. There’s no time to build it back up. That’s certainly true. You can’t have an original idea when your day is scheduled in five-minute chunks. You’re just performing one task after another, and a lot of it is routine—grip and grin, getting your picture taken, meeting with the boy’s club boy of the year, meeting the volleyball championship team. A lot of it is spent on that sort of stuff. I think even he came to office thinking the presidency had a lot more power than it does. I would say that’s a constant of my journalistic world: every president I’ve covered has learned that the office is in some ways much weaker than they anticipated. In some ways they still think it has some power, but it’s not an awesomely powerful office.

CM: You have to write a column twice a week. Is there something about that pressure that affects the way you go about your everyday life? Do you always have to have a certain type of reaction to the news?

DB: Every second is, “Can I get a column out of this? Can I get a column out of that?” There’s no second when you’re not thinking about that. That’s seven days a week. It’s a constant lookout.

CM: Do you have to impose your perspective on every significant news story for the sake of potential columns?

DB: Yeah, you try to impose. You used to be able, before the internet, to watch a presidential debate and then two days later write your thoughts. Now there’s so much blog and Twitter reaction; you can’t write that column anymore. It’s too late. Even if you write the next morning you feel it’s too late. People have lost interest in it. You do have to get some outside information or get ahead of the news, or at least some distance from it so that you have something new to say.

CM: Is there something about always having to form opinions in the op-ed column format that’s changed your general outlook on politics and society?

DB: I’m less happy. I’m always anxious that I’m not going to have something to write about next time. There’s a lot more anxiety. And after the opinion comes out, there’s always the incoming criticism. That took some getting used to.

CM: What kind of effect does it have on you when you go on Sunday shows and on NewsHour and on NPR, or even in private, and people always want your thoughts, your views, your opinions on things?

DB: The shows are fine. I enjoy them. Usually I’ve formed an opinion by the time Friday comes along, so it’s no sweat. Sometimes on the shows you meet the newsmakers in the green room beforehand. You learn some stuff every Sunday just chit-chatting with them. One thing I do when I’m out at a dinner party—I don’t do that. I do that for a living, so if I’m at a dinner party and the conversation turns to politics, I pretty regularly clam up. I’m just not in the mood when I’m relaxing.

CM: Do people respect that?

DB: Sometimes they force you; sometimes they think you’re condescending to them because you’re not doing it. They think “Oh, he thinks he’s so superior; he’s not sharing his opinions.” I’m just lazy; I don’t want to do work when I’m out at somebody’s house for dinner.

CM: Is there something about having a recognizable voice?

DB: My voice changed; it’s not the voice I thought I would have. I thought I was going to do a more humorous column, which I had done in my career before. But I’m more conservative than our readers, and if they’re not with you they’re not going to laugh at you. It became a more 1950s, 1960s Jane Jacobs middlebrow column. There’s a certain style of writer—David Riesman, Daniel Bell, Jane Jacobs—who were writers in the 1950s, sort of a little above journalism, a little below academia. My column became more like that. I only realized about a year into the job that it was going to be that sort of thing.

CM: Do you find it important to your writing character to include humor?

DB: I used to, like when I wrote for the Maroon. I’ve done it less since the pressure to churn out two columns a week is greater, and I think as you get older your mind gets a little less fertile for jokes. Humor is more or less a young person’s game. You get a little more ponderous and earnest as you get older.

DB: They use me as the butt of jokes too much.

CM: Are you constantly aware of how large your audience is?

DB: You feel that. You can’t think about that. You write to one person. You write to interest yourself. Whoever you are, you write to a specific reader…. Whoever the people are out there—I don’t know them, so they can make of it what they can. I can’t control their reaction because I don’t know who they are.

CM: But because of how cross-platform your approach is now, on TV, radio, and in the newspaper, do you ever think about how to centralize your audience in some way? Is that part of having readers who appreciate your voice?

DB: The shows feel weirdly intimate. Writing, I write for one person. The shows are intimate. You’re on set, and there are cameras around, but mostly it’s you and the host and the other guests, and you know them all reasonably well by now. So you really are not that aware of the audience when you’re having the conversation. It’s like my little version of show business. I enjoy it. There are some shows that I used to do that I didn’t enjoy so much, so I stopped doing them. I’m lucky enough now that I only have to do the shows I enjoy.

CM: Do you think there’s a tendency to characterize you in a certain way that makes you mockable? What about your writing, your voice, your personality, can encourage that kind of reaction?

DB: There are a lot of people who just mock Times columnists. That’s part of the job. I’m struck by the power of labels, the power of the word “conservative.” A lot of real conservatives don’t consider me conservative at all. Most people, especially people center-left, see me through that prism. Whatever I write, they interpret it through that prism.

CM: As an aside, do you think there’s a divide between conservative thinking and Republican Party thinking?

DB: Not so much anymore. When I started at The National Review, there was a sharp divide. We looked down on Republicans because they had no ideas and they sold you out. They were corporate cogs. Now, Republicans have moved toward conservatism and conservative intellectual institutions have been folded into the Republican Party all in one. The divide is disappearing to the detriment of both sides.

CM: Back to your columns. Do you ever read comments on your work?

DB: Stuff comes to my email. I’ll occasionally look at comments, and then you get some feedback just organically. I never Google my name; I never look too much at the blog commentary; I don’t look at the comments too much. It’s too psychologically damaging.

CM: Have you actually been seriously affected by responses to your columns?

DB: In the first six months on the job I was going through everything. Most of it is harshly critical, so it was debilitating. I stopped.

CM: Is that why you view your writing process as something to be protected?

DB: It’s just a more natural process; it’s manageable. Maybe this was evolution—how we’re trained to communicate. We’re trained to communicate to a person, not a mass audience. You just develop that style. You’re certainly not thinking about how to influence readers of the world.

CM: The cliché about “making a difference”—is that even something that can apply to you as a writer in an influential position?

DB: Not in the way it’s traditionally described. I’ve never had a politician or a president call me up after a column and say, “You know I looked at it this way, but then I read your column and realized I was wrong.” The politicians just want to know if I’m for them or against them, and if I’m against them then they’ll call up. I said something on the air last Friday and literally as I got off the set, the person I was talking about was on my cellphone, telling me how wrong I was about something he’d done. They just want to know if I’m giving them good press or bad press. The people you hope to influence are outside of power—younger people. It’s like being a teacher. There’s a good phrase: that writing provides a context in which other people can think. You’re really not trying to tell them what to think—you’re trying to give them a context in which they can have a discussion with themselves about a subject.

CM: Do you have to have confidence that the type of success you’ve had means you’re doing something right?

DB: You have to have confidence in your own tastes—what interests me is what I’m going to write about. I’m going to write about what was most interesting to me that week. Even if you’re not totally sure, you’re not a total expert on the subject, you have to have enough confidence to throw yourself out there even while knowing you could be completely wrong.

CM: You’re on the board of the new Institute of Politics at UChicago. What do you think it’s doing for the school?

DB: The school, decades ago, was completely divorced from the real world. We read no newspapers; we were stuck in 3rd Century Athens, and no one came to campus who wasn’t an academic. I think the IOP, the Paulson Institute, the Becker-Friedman Institute—they’re all bringing a part of the real world to campus. The students need the academia, but it’s good to meet people who are out doing what Axelrod has been doing for his life.

CM: What about the IOP, if anything, conflicts with the core mission of the College?

DB: If I were Dean Boyer, I’d worry about if we’re upholding the standards of the University as traditionally defined. Are we becoming more like Harvard, frankly, which is more Kennedy School–type professional ground, and that’s not who we are. If he or anybody had those concerns—we’ve got a long way to go before we become too professional and too practical. Chicago is still pretty Chicago.

CM: You tend to have a highly structured writing style. What are your best pieces of advice for becoming a better writer? If you want to become a journalist, is it more important to improve writing in a traditional sense instead of learning the craft of the profession?

DB: I think you can learn the craft, especially of news writing, later. I tell my own kids, who don’t listen, that 80 percent of writing is organization, is traffic management. What I do is I write down stuff on a piece of paper and Xerox it, then lay it out in piles on a table or floor, and so each pile is a paragraph. So I spend a lot of time on structure. With books, I spend an awesome amount of time on structure, getting things in the right order. By the time I sit down at my keyboard I’m 80 percent done with the column. The ideas have all been thought. I don’t really think any new thought at the keyboard. I carry notebooks around. Getting the structure right is super important. The other thing is that unlike in college, no one is paid to read your writing, so you better be reasonably compelling or else they’ll just click off to something else.

CM: So I read somewhere that you listen to rap music. Who are you listening to now?

DB: [Laughs] It’s true. I was at a Nas concert! I can barely stomach Tyler the Creator, who gets a little raw for me. I come into contact with them through my kids, so they’re my avenue into the world.

CM: And the only question that can come last: what’s your experience with Harold’s Chicken?

DB: OK, so this is a confession: I was a big fan of Harold’s Chicken. When I was last on campus a couple of months ago, I walked in there fully expecting to order my usual half white. Somehow I just didn’t want to. It’s a new store compared to when I was there. I ate at Cedar’s next door instead; it was more the kind of salad a middle-aged person has.

Interview has been condensed and edited.