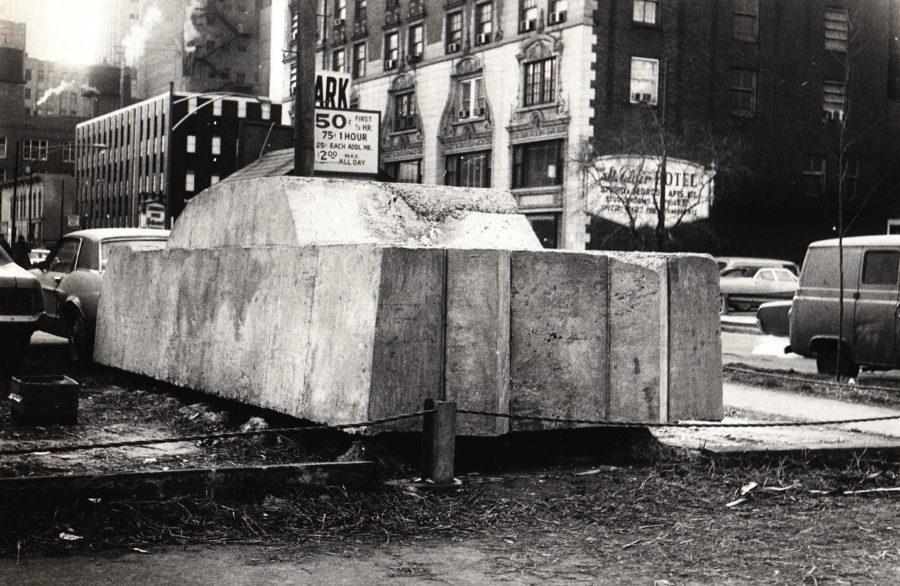

Picture this: a 1957 Cadillac, almost entirely encased in 14 tons of concrete, parked in the east wing of the Campus North Parking Garage.

The sculpture, created by Fluxus artist Wolf Vostell in 1970, is “Concrete Traffic.” Commissioned by the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago (MCA) back in 1969 and encased in concrete on January 16, 1970, the sculpture was given to the University of Chicago as a gift on June 13 of the same year.

“The MCA was not yet a collecting institution and was seeking to give the sculpture to a local university,” Christine Mehring said. Mehring is the head of the Concrete Happenings initiative as well as the chair of the art history department. “UChicago took it because the head of Midway Studio [at the time], artist and professor Harold Haydon, who also designed the stained glass windows at Rockefeller Chapel, lobbied for it and made it happen.”

Rain or shine, the concrete car remained parked outside Midway Studios for almost 40 years. On May 30, 2009, however, the sculpture was forced to move to a storage and conservation facility in Humboldt Park to make way for the construction of the Logan Center for the Arts.

Now, after almost eight years, the car is finally back on campus, thanks to President Robert Zimmer’s approval last April and the colossal efforts of a dedicated conservation team led by Mehring since 2011.

But one might wonder—why go to such lengths to conserve a concrete car?

The sculpture is of tremendous historical significance. Vostell was the leading German proponent of the Fluxus movement, and “Concrete Traffic” is the largest Fluxus object that exists today, which is notable, considering that Fluxus was largely a performance-based art movement that dealt with intangible media. As Mehring explained, Fluxus was also the first transatlantic art movement; indeed, a plastic ‘twin’ of “Concrete Traffic” (“Ruhender Verkehr,” 1969) exists in downtown Cologne. As a sculpture that was created using nontraditional materials—which Mehring considers the trademark of 20th-century art—“Concrete Traffic” further marks an important movement in art history.

As a large sculpture, “Concrete Traffic” fittingly tackles big themes. It is no coincidence that Vostell chose to encase a Cadillac in concrete, immobilizing an iconic American car that fascinated countless West German youth after the war.

“On one hand, it reflected the German artist’s attraction to America’s postwar dynamism, ‘preserving’ the Cadillac as a symbol of the country’s prosperity, mobility, and optimism,” Mehring commented. “On the other, it critiqued the destructive tendencies of contemporary American politics and society—riven by racism, violence, and the Vietnam War—by rendering the car nonfunctional, virtually unmovable, and more visually akin to a tank or machine of war.”

So when Mehring, already aware of “Ruhender Verkehr,” realized that “Concrete Traffic” was being kept in Humboldt Park, she considered it “the discovery of a lifetime”—but was at once thrilled and devastated upon seeing the sculpture.

“[It] was in terrible condition,” she remembered. “I don’t think I have ever felt such an instant sense of responsibility for something that I had no idea how to live up to…. What was the right thing to do? …How could I possibly gather all needed information? …How would I convince anyone to help save this sculpture, let alone bring it back to campus?”

On September 30, the Cadillac made its way back to Hyde Park as part of a public procession. Starting from Humboldt Park, it stopped by the MCA, the Arts Club of Chicago, Midway Studios, and the Logan Center, before finally arriving at its new home in the Campus North Parking Garage. At the Drive-In Happening, the official launch event for the sculpture on October 14, the garage transformed into a screening space for several of Vostell’s films. Five were projected onto the walls of the parking lot using projectors stationed atop cars and equipment from the Logan Center media cage that hung from the ceilings.

As Mehring explained, Fluxus was a movement that was largely centered around “Happenings:” performances or public events that usually involved audience participation. Vostell used film not just because of his material but also because of how it could project. The artwork he created was inserted into everyday life and places, although it often took on bizarre forms. One of the films, Berlinfieber, captured a Happening that took place on the streets of Berlin in 1973. Like many of Vostell’s Happenings, the participants who took part in Berlinfieber had to follow a ‘score’ that instructed them on how to behave as the camera rolled. In this case, the drivers lined their cars up in rows of ten as closely as they could and drove extremely slowly, all the while recording their movements on paper. They then would carry out a ritual of opening and closing the trunks of their cars 750 times, each time inserting or removing a white plate. Finally, they would tape the written record of their movements to the inside of the trunk and only remove it the next time they came down with a fever.

“[It’s] very much in the spirit of Fluxus in the sense that this is a very multimedia event,” Mehring said about the Drive-In Happening, adding that Fluxus artwork involved a lot of filmmaking, sculptures, and unusual materials. Having the Drive-In Happening take place in a regular parking lot while transforming it into an unconventional art space was therefore quite fitting.

But where was the famous Cadillac itself amid all this commotion on the night of October 14? On the side of the parking lot, unfrequented at first, but later surrounded by visitors who leaned against its concrete sides making small talk as children explored the sculpture by walking on its concrete top. There was a sense of normalcy surrounding the public sculpture itself, almost as if it were just another regular car parked in the garage—although the steel structure that engineers erected to support the concrete car in the basement below shows just how much work was necessary to make it possible for the Cadillac to ‘park.’

Indeed, “Concrete Traffic”—although seemingly self-explanatory (it is best described, after all, as an old car encased in concrete)—is laden with intricacies that have complicated, and still affect, its conservation process.

Mehring found the car in a worrisome condition: When conservation first began in 2011, the concrete on the car was falling and cracking from years of neglect. The entire car also needed to be cleaned because biological growth had developed on the concrete’s surface, obscuring the original marks Vostell left behind while making the sculpture. Furthermore, the salt that had originally been added to the concrete to make it dry faster had made the concrete less stable (as a creative touch, salt was added to the rye beer that Arcade Brewery had specially designed for the installation).

“At the moment, we have stabilized the structure and the cracks,” said Lisa Zaher, who has been involved with the project since 2013 and became the first UChicago Arts conservation research fellow last year. “The area we are still addressing concerns the patches at the front and back, and there is still some discussion about the area[s of patching] at the front of the sculpture known as Dagmars.”

Understanding how to conserve the sculpture also meant having to understand Vostell’s original artistic vision. Looking at archival images helped Mehring and her team to conclude that Vostell originally wanted the sculpture to look as if it was solely supported by its tires—although the weight of the concrete made this a structural impossibility.

“Our task was to create a support structure that maintains the illusion of the sculpture as freestanding while ensuring the structural integrity of the concrete shell,” Mehring said. “This was an enormous challenge.”

Anna Weiss-Pfau, the UChicago campus art collection coordinator and conservator who has been heavily involved with the sculpture’s movement and engineering over the past few years, also expressed concerns about protecting the car from natural elements and visitors. “Any time a condition issue arises for the sculpture, or organic debris or grease from the nearby cafeteria accumulate, it will have to be removed,” she said, pointing to how the conservation of the sculpture continues long after its installation. Indeed, she wishes that all of the sculptures on campus could receive the same level of care that is being given to “Concrete Traffic.” “My hope is that this project just created an entire campus of conservation advocates and individuals interested in the theoretical complexities of decision-making around public art,” she said.

Mehring did not exaggerate when she said at the Drive-In Happening that the entire initiative is an “incredible conservation effort.” Just as Fluxus was a very collaborative movement (for example, Vostell collaborated with Ulrike Ottinger, an avant-garde and documentary filmmaker, to film Berlinfieber), the whole process of turning Concrete Happenings into a reality involved collaboration on a citywide scale.

“Over the years I put together an incredible team to help bring this sculpture back, to research it and to conserve it and to actually move it here into the parking garage,” Mehring reflected.

Just within the campus community, the Happening involved the Department of Art History, the Neubauer Collegium for Culture and Society, the Smart Museum of Art, the Special Collections Research Center, and the Logan Center. Beyond UChicago, Mehring and her team worked with the MCA, engineers, car restoration specialists, and cultural heritage conservators to conserve the sculpture.

And now, Concrete Happenings is making its presence known over campus, with a strong lineup of events that will run until next May, including more screenings of Vostell’s 16 mm films and talks on concrete poetry. On January 22, three free exhibitions will open at the Neubauer Collegium, the Smart Museum, and Special Collections to further explore the history of “Concrete Traffic.”

“A public sculpture really has to be in a public space to be itself,” Mehring said about “Concrete Traffic” at the Drive-In Happening. “This sculpture had to be where a real car can be.”

Minutes away from the Smart Museum and the newly-built Campus North Residential Commons, “Concrete Traffic” represents the intersection of visual art and campus life, marking it as an object of significance in not only art history but also the University’s past. Its conservation process is a testament to the importance of preserving this history for generations to come, ensuring that—although the car is stationed in place—its legacy will travel far into the future.

To find out more about Concrete Happenings, visit https://arts.uchicago.edu/concrete-happenings