Eighteen hundred students crammed into Rockefeller Chapel on the first day of classes last fall when then-Democratic candidate Bernie Sanders took a break from the campaign trail to give a speech at his alma mater. Campus reveled in the candidate’s UChicago past as fans circulated a handful of black-and-white images on Overheard and Twitter: Sanders, book in hand, leading a packed sit-in; Sanders seated among fellow activists; Sanders on a podium. The speech, along with the photos,was a hit.

But amid the fanfare, few wondered: who was at the other end of that camera lens? This invisible student had attended all the same rallies. He had stood on the same stages. He had known Sanders—they had even shared a roommate. And his photos? They’re now hanging in New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art.

Photographer, filmmaker, and writer Danny Lyon is, like Sanders, a Jew from New York. He entered the College in 1959 at age17, just two years before the senator. Lyon was young, eager, and armed with a new camera—an Exa 35mm SLR he had purchased in Munich that summer while backpacking in Europe. Lyon’s father, a German-born physician-photographer who fled to the States to escape Nazi rule, remembered the local photography shop from his youth and suggested his son check it out.

“I didn’t think of myself as having any talent. I couldn’t paint—or draw. I was no musician. But put a camera in my hand—I was a natural,” Lyon said.

By the time Lyon got to campus, he had only been shooting film for a few months, but he had already developed a knack for the craft. Desperate for access to a darkroom where he could develop his rolls, Lyon quickly joined The Maroon as a staff photographer and spent hours in the 100-square-foot darkroom in the basement of Ida Noyes Hall.

“I learned to develop film in that darkroom,” Lyon said.

A prolific writer and diarist, Lyon never wrote for The Maroon. (“Student papers are like self-publishing. No one really cares about it.”) Instead, he stuck to images. Lyon would frequently go to the darkroom to make “murals”—large-scale prints on Kodak paper five feet across. To fund his work, Lyon won a scholarship for his photographs, worked on the college yearbook, and moonlighted for the Alumni Magazine. It wasn’t long before Lyon became known on campus as a photographer—and, soon thereafter, the photographer.

Lyon, however, didn’t study art or photography. He majored in history with a minor in philosophy. Over the course of our hour-long conversation, he name-dropped nearly every theorist studied in the first two quarters of Classics (“Actually, Herodotus is much more interesting than Thucydides”), spoke lovingly of Burke’s On Conciliation with the Colonies (“You know, this wasn’t written on a street corner”), and quoted Jefferson, Lincoln, and—why not—Doctor Zhivago.

While Lyon was a decent student, he dedicated much more time to CORE than to the Core. By his third year, the civil rights movement was in full swing, and the student arm of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) was mobilizing against segregationist policies in University-owned housing.

In the January 17, 1962 issue of The Maroon, then-President of the University George Beadle responded to critics of his housing policies, saying, “In this practical and far from ideal world you have to move slowly enough so that you don’t lose. If the University had immediately integrated all the houses in Hyde Park that it bought 10 years ago…the University wouldn’t be here today.”

His statement was met with outrage. By noon the next day, 200 protesters had gathered outside the administration building holding signs: “Don’t Equivocate, Integrate!” and “Urban renewal, not Negro removal!” Bernie Sanders, chairman of CORE’s social action committee at the time, mounted the steps, delivered a speech, and led 33 demonstrators—31 students and two local CORE representatives—up to President Beadle’s fifth-floor office, where they spent the night. (Sound familiar?)

“There was a sit-in inside the administration building protesting discrimination against blacks in University-owned housing,” Lyon said. “I went to it with a CORE activist and friend. The sit-in was in a crowded hallway, blocking the entrance to the office of Dr. George Beadle.”

And with a click, the film negatives of Sanders leading Chicago’s first civil rights sit-in—or, rather, “sleep-in”—came to light. Over the next week there were more sit-ins, including a confrontation at the University Realty office. In the end, Beadle and his opponents reached a compromise: Beadle appointed a committee of three faculty members to investigate the University’s housing policies.

As a photographer present at all the events and protests, Lyon eventually evolved from observer to participant. “By senior year, I’m an activist,” he said.

The summer before his fourth year, Lyon hitchhiked south. He first stopped in Cairo, IL to hear a speech by John Lewis, who was then chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and is now a U.S. Representative from Georgia. Lyon then made two trips to Albany, GA, where he was arrested three times, once alongside Martin Luther King Jr.

“I was in Albany about 30 seconds when the police picked me up for talking to a Negro on the bus,” Lyon told The Maroon in 1962. The stranger on the bus turned out to be Wyatt T. Walker, King’s secretary.

Before long, the director of SNCC had recruited Lyon as the organization’s first official photographer; he would resume work there as a staff photographer after graduation. Lyon began to travel with SNCC. He captured sit-ins, speeches, marches, and violence, quickly transferring images from darkroom to poster board. He documented the aftermath of the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham, AL; female protesters locked in a stockade in Leesburg, GA; and confrontations with the National Guard in Cambridge, MA.

When he returned to campus for his final year, Lyon’s photo series went on display for two weeks in the lounge of the New Dorm, later renamed Woodward Court. The Maroon ran a full-page spread of his work that fall, on October 23. One image in the upper right-hand corner of that issue, a shot of a man waiting in line to enter a segregated swimming pool in Cairo, now rests on the fifth floor of the Whitney, next to a photo of SNCC member Stokely Carmichael.

The image directly below features John Lewis (left) kneeling on the pavement at a Cairo prayer demonstration. The three other images on that page—police carrying a member of SNCC out of a sit-in, a deserted Albany street, and two pained children in Cairo—have been shown in exhibitions across the country.

The Whitney’s Danny Lyon: Message to the Future, organized by the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, is the photographer’s first comprehensive retrospective. The show features more than 175 images—including gelatin prints and 2-D collages—as well as three of Lyon’s short films and several of his personal objects.

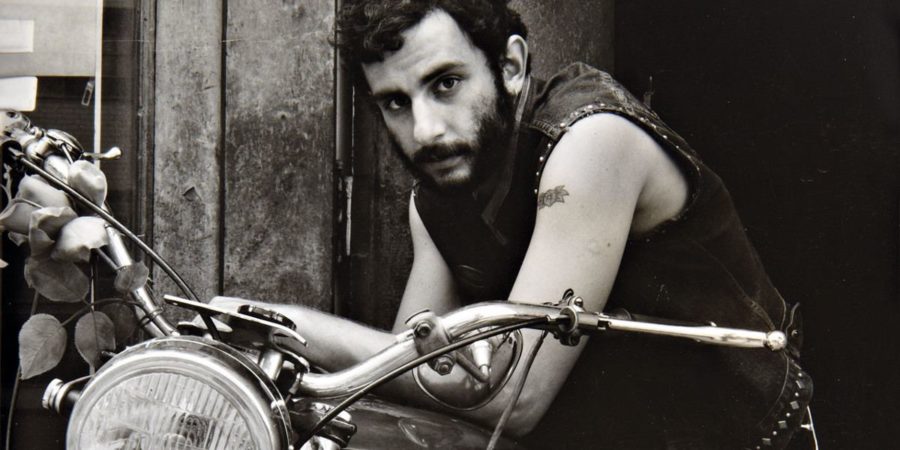

If not for the accessible curation, the scope of the work would be overwhelming. The exhibit proceeds chronologically, with each period of Lyon’s work in its own room. First, the 1960s. Next, Lyon’s various forays into the fringes of society, from his fixation on the tattooed, leather-jacketed Chicago Outlaws Motorcycle Club (mid-’60s) to the inmates of the Texas Department of Corrections (1986–7). In each series, Lyon captures the grittiest subjects with the dignity and grace of an Avedon portrait.

“I’ve always had a dark side. I always was attracted to the criminal. There’s something about America that excites that,” Lyon said.

“How can you make anything of your life if you’re not free? So much of this country is about greed. If your needs of life prevent you from being free, go rob a bank. Become a Luddite. Steal a bicycle. Don’t eat.”

As it explores the social and political issues of his time, the exhibit raises questions over whether Lyon’s work is photojournalism or art. (In 2011, the Missouri School of Journalism posited one answer when it awarded Lyon the Missouri Honor Medal for Distinguished Service in Journalism.) But no matter what it is, it is clear why Lyon’s work was successful. Lyon didn’t just photograph subjects—he photographed his friends, his confidants, his temporary family. When it came time to position the camera, every shot was a self-portrait.

He also did far more than point and shoot. Lyon kept copious records of his ventures. He archived hours of interviews and conversations, many of which he later compiled into books like 1968’sThe Bikeriders. Lyon’s book compilations—along with his visual works—are steeped in the Core.

“I reference and write about the classics all the time. I still remember Professor Oost’scourse in ancient history,” Lyon said.

Lyon’s photographs guide the viewer through conversations that return to the fundamentals of life and theory. On one photograph commemorating the deaths of photographer Walker Evans and writer James Agee, Lyon wrote in a thick black pen: “So great was his vision, so powerful his art. We will be forever remembered and honored by his work. Like Plato, he seems to have found reality itself.”

While the philosophy minor may have stuck with him, this history major doesn’t seem too fond of rehashing the events of times past. A visual historian, Lyon has dedicated his life to recording history, but only to prevent repetition.

“What’s the point of talking about the past? Donald Trump is running for president. This is real. My father was a student in Germany when Adolf Hitler was a minor politician. And people thought he was comical too,” Lyon said.

Thus his retrospective is not a glorification of dust, but, as its title states, a message to the future.

“Look, I’m not going to go be a famous artist in New York. I’m going to take what I learned and do something with it. I never even liked museums, but real life is not in a museum. It’s not on campus. You need to get out there. If we all did, we’d change America.”

When the Whitney’s chief curator Julian Cox first scheduled Lyon’s retrospective for this summer, did he anticipate the tragedies to come? The summer of Orlando, of Dallas, of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile? Of, now, Keith Scott and Terence Crutcher?

When we spoke, Lyon was calling from a motel about 175 miles from his New Mexico home. He was staying there for two days to fish along the San Juan River (“This river is one of the great fisheries of North America,” he said, as if to himself), and I was keeping him from his rainbow trout. But I had to know—did he still talk to Sanders?

“When Bernie Sanders spoke in Albuquerque, Nancy and I were taken backstage to meet him,” Lyon said, recalling Sanders’s campaign stop this past May. “Bernie remembered me, but I didn’t remember him. He said to me: ‘Oh my god, Danny Lyon. You have a bigger camera now.’”

Danny Lyon: Message to the Future closes September 25, reopening at the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco on November 5, then again in Germany. Lyon recently authored two books, Burn Zone and Story of Sam.