Picture an image of the Civil Rights Movement. You’ll probably see it in black-and-white—a film shot from the 1960s. Is it Selma? Montgomery? Maybe Birmingham? Can you conjure a single image that wasn’t taken in the South?

Despite what this trove of paradigmatic photos might imply, the Civil Rights Movement took place in the North too: It was just as hard-fought, complex, and, at times, brutally violent. North of Dixie: Civil Rights Photography Beyond the South, the third book by historian and author Mark Speltz, published by Getty this past November, seeks to rectify this narrative absence. The book compiles 100 photographs taken in the North, Midwest, and West from 1938 to 1970, shedding light on forgotten narratives in the movement and complicating our notions of its participants.

Speltz spoke with The Maroon in advance of his talk at the DuSable Museum of African American History on January 12.

Mark Speltz: The goal of the book is to really look past the iconic photographs that we see all the time in our high school textbooks and short Black History Month documentaries about the Civil Rights Movement. They tend to tell a very heroic, non-violent story of the movement, fought and won in the South. My thought was: We need to understand the full extent of the movement. People have begun to bring in the stories of young individuals who led the movement, women, leaders of local grassroots movements—to look beyond the charismatic male leaders and politicians. Let’s look beyond the South. Let’s look at photos of how civil rights played out in the North and the West.Chicago Maroon: Can you tell me a little bit about your book?

CM: How did this project evolve?

MS: It started as a graduate school project about 10 years ago in a photography and visual culture class. I was asked to read a photograph, interpret it. Tell a story about it. Who’s the source? Is it truthful? I knew I wanted to do Civil Rights–era photography because I’d always been drawn to it. I was going to grad school in Milwaukee, and my adviser said, “Why don’t you look at Milwaukee Civil Rights?” So I followed her suggestion. At the time, it was the 40th anniversary of the Open Housing Movement.

There were books upon books published in the last decade or two about the struggle in Chicago—or Milwaukee, Cleveland, Seattle, L.A. Still the traditional movement narrative overemphasizes the South—the most dramatic clashes that captured America’s attention. Yet our focus on those allowed many other grassroots struggles to fall by the wayside. They may have been known at the time, but they were left out of the narrative.

CM: How were they left out of the narrative?

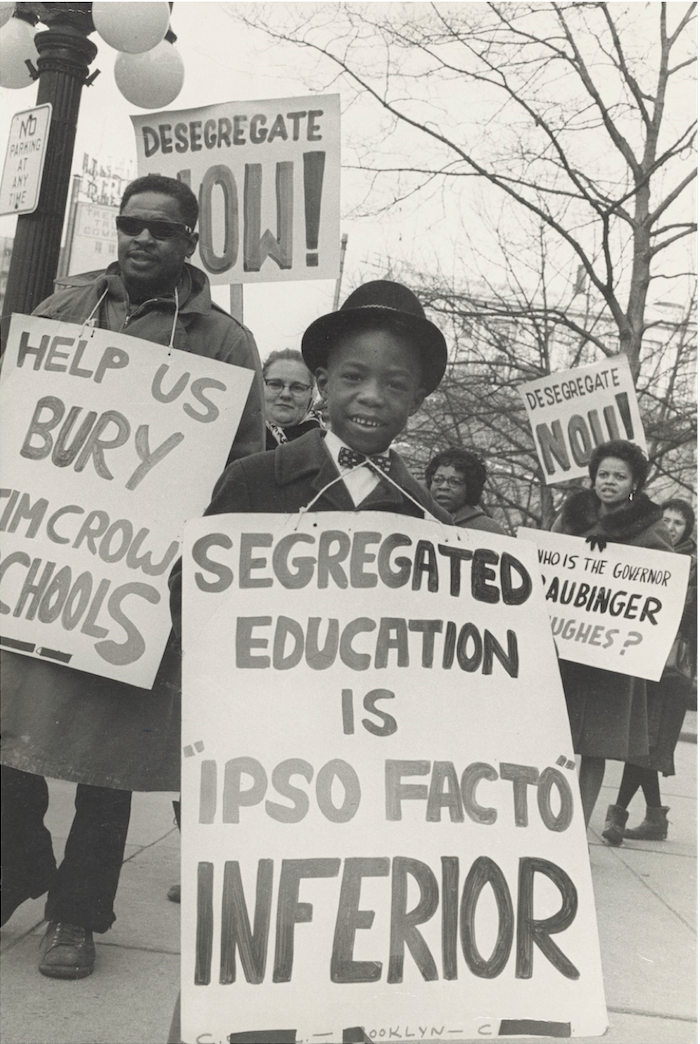

MS: The press and many of the major northern news outlets much preferred to point a finger at Southern racial issues and politicians. They had long proclaimed that America’s racial issues were a southern problem, and they didn’t want to look at what was going on in their own backyard. Press coverage of police brutality in Detroit would be buried, but they happily ran photos of police dogs biting protestors in Birmingham in 1963. It painted the picture of a non-violent civil rights struggle and didn’t focus on issues in their own community—housing, employment, and racist practices in the North.

Ever since, it has been really easy to celebrate the victories—the hard-fought legislative victories, the martyred leaders, the speeches—but that’s what captured 99 percent of the attention. Other things were set aside. You can tell the “look at what we were able to achieve” story by focusing on voting rights, desegregated buses, and lunch counter sit-ins—all incredibly important victories—but one should remember to include other locations, where the story was more complex.

[Photographer] Art Shay did a lot of work in Chicago, and he captured that scene well. Other people, like Danny Lyon, would travel with SNCC. He shot in Cairo, the most southern part of Illinois. He shot the March on Washington. People like Bob Adelman shot for the Congress of Racial Equality in New York and later on assignment in the North and South. When I started working on the book and reached out to him, he probably sent me about 2,000 photographs from only in the North. He actually passed away this year, so it was pretty incredible to work with him on the book before he passed away.

CM: I see that you broke the book into four chapters. How did you decide to group the images?

MS: That was one of the first and hardest things. I could have done it chronologically because I cover about four decades. But I felt it would be stronger if I broke it into subjects. First: under-exposed, lesser-known stories, lesser-known marches, lesser-known reactions. How did people in Chicago react when there were marches in Cicero?

The next chapter focuses on how civil rights organizations used the camera to promote their cause—using photos on pamphlets, signs, brochures. How did they use them to combat police brutality?

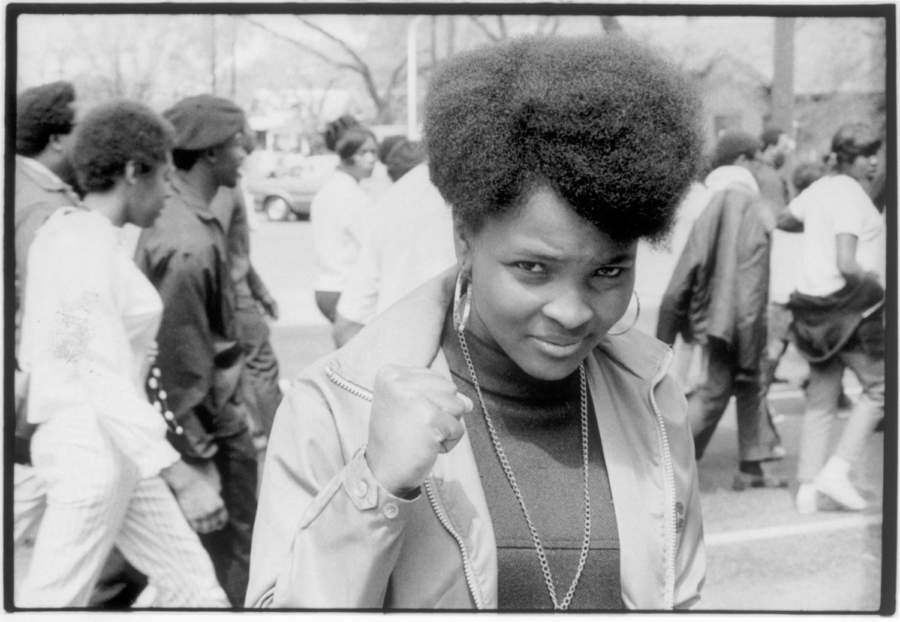

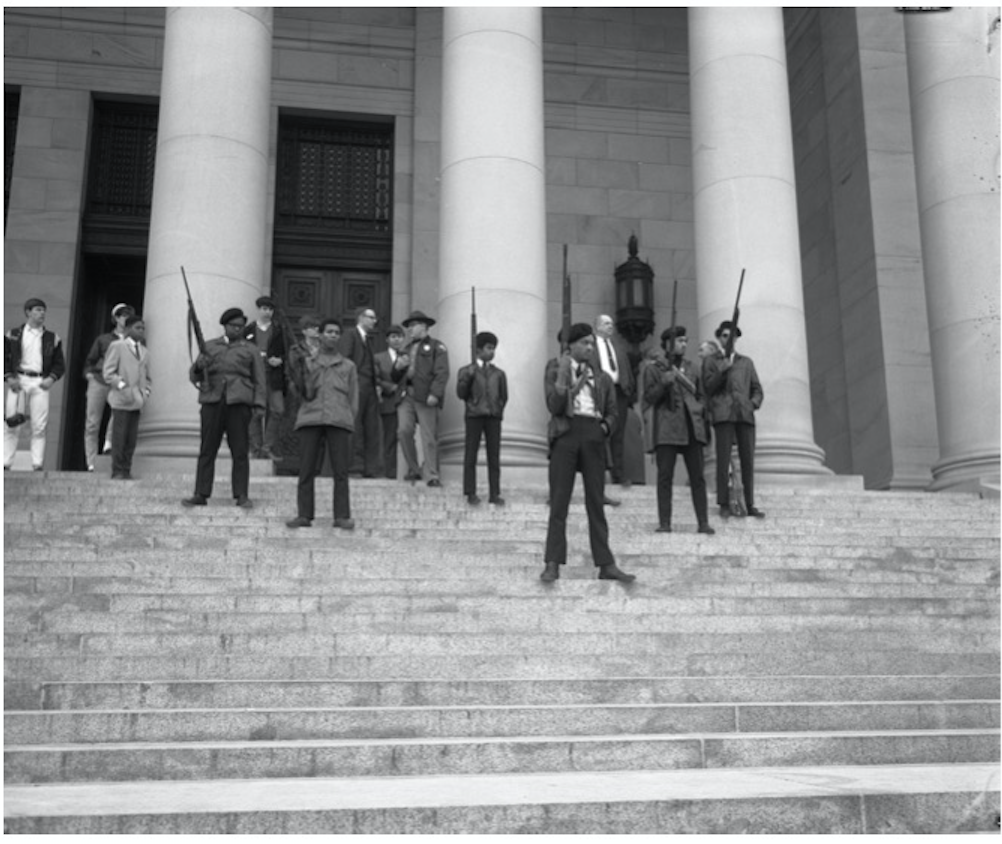

The third one looks at black power. You hear the words “black power,” and many immediately think of fists raised, the berets, the Black Panthers. You might think guns, anti-police. I wanted to use the photographs to show that black power meant so much more than that. You could see a kid in Toledo getting a free coat from a free clothing program. You could see kids in Oakland getting a warm breakfast. So it wasn’t just male bravado and guns; it was also community programs.

The fourth chapter sort of sits by itself. I turned the camera around and looked at how it was used against the movement. How did the police, the FBI, Chicago’s Red Squad use photography to disrupt or subvert the civil rights struggle? We don’t know a lot about how police would stand on the sidewalks and take pictures of people who were protesting. I have a 1970s photo in there that the Chicago Police Department took of an anti-police brutality march. There’s a number one on there, and on the back is the woman’s name. So they were building surveillance files. Several lawsuits later, these files ended up at the Chicago History Museum. Then I had to get permission from the individuals or their families, so I had to go to great lengths to use about five or six photos for that collection.

In Seattle, as I looked through a digitized collection online, I started to realize that people were covering their faces. There was one where a little boy was sticking his tongue out at the photographer. When I dug a little more with the archivist at the Seattle Municipal Archives, she found a document in the mayoral collection of photos taken by the Seattle city police and sent to the mayor saying: This is who was there, and this is what we know about them. Surveillance—sometimes for practical reasons, sometimes used to penalize people and discredit civil rights organizations.

CM: You’ve written about your admiration of contemporary photographers like Sheila Pree Bright, Devin Allen, and Patience Zalanga. How do these photographers compare to those you discuss in your book?

MS: I see them in a long line of photographers who are making art and making statements. Several of them are looking back and realizing the lineages of their work—the African-American photographers before them. Their work is documenting important protests in the streets, and whether their photos are in newspapers, or magazines, or the cover of Time, like Devin Allen’s photos of Baltimore were, they’re circulating much further via social media than any Civil Rights photographer could have hoped for, especially these past two years from Cleveland to Baltimore, to Baton Rouge, and St. Paul.

CM: What do you hope to focus on in your upcoming talk?

MS: I’ll explore what we can learn by revealing a broader, more expansive view of the movement. I’ll show a dozen photographs or so and talk about how the book came to be. I’ll definitely focus on some Chicago photographs and photographers: Art Shay, Bobby Sengstacke, Declan Haun—his collections are at the Chicago History Museum. Even how gangs and youth groups used photography at the time.

There’s one Chicago photograph on page 99. It’s by Art Shay. It’s a gentleman looking out a door, and he’s a member of the Black Panthers party. He’s pointing to all these bullet holes in the door because there was a raid on the chapter headquarters. And if that’s the only thing you see, then you only see one side of the story: the violence. But on the left side of the photograph, there’s a clearly visible sign that says “Free Breakfast for Children.” It begins to allude to their role and place in the community—beyond the armed, macho revolutionary. And that door is at the DuSable Museum in the basement—or at least believed to be the one in the photograph.

CM: What’s next for you?

MS: I’m interested in exploring Malcolm X and the photographs he took himself.

CM: That he took?

MS: Yes. It’s funny, he told the famous photographer Gordon Parks that he carried a camera for “collecting evidence.” He would sometimes wear it into a courtroom or to a protest. He’s seen with Muhammad Ali taking photographs of him. He was incredibly aware of how to create an image fitting how you want to be seen. I have a photograph of him in Chicago holding a newspaper—the Nation of Islam’s paper Muhammad Speaks—and on the cover there’s a photo of a scene in L.A. where a Nation of Islam member was shot by the police with a big, bold headline. He was redirecting the viewer’s attention to see the story he wants you to see: the story of police brutality.

Speltz’s talk will run 6:30–8:30 p.m. on Thursday, January 12, in the Ames Auditorium of the DuSable Museum of African American History at 740 East 56th Place. Tickets are $10 at http://www.dusablemuseum.org.