University of Chicago hospital patient information was potentially vulnerable to hackers due to weaknesses in the University’s network, a Maroon investigation revealed. Experts suspect that vulnerabilities like these are likely to be found at many hospitals, universities, and institutions around the world.

The weeks-long investigation, encompassing a manual review of tens of thousands of lines of network scan logs, interviews with sources who have explored the University’s network, and conversations with multiple cybersecurity experts, found that networked printers accessible by anyone on the University network were being used to print what seemed to be sensitive health documents, like organ donation logs, surgery face sheets, prescriptions, and even medical records—some of which may have been protected by federal privacy law. Researchers have shown that documents printed on printers like these are vulnerable to being remotely stolen by hackers relatively easily.

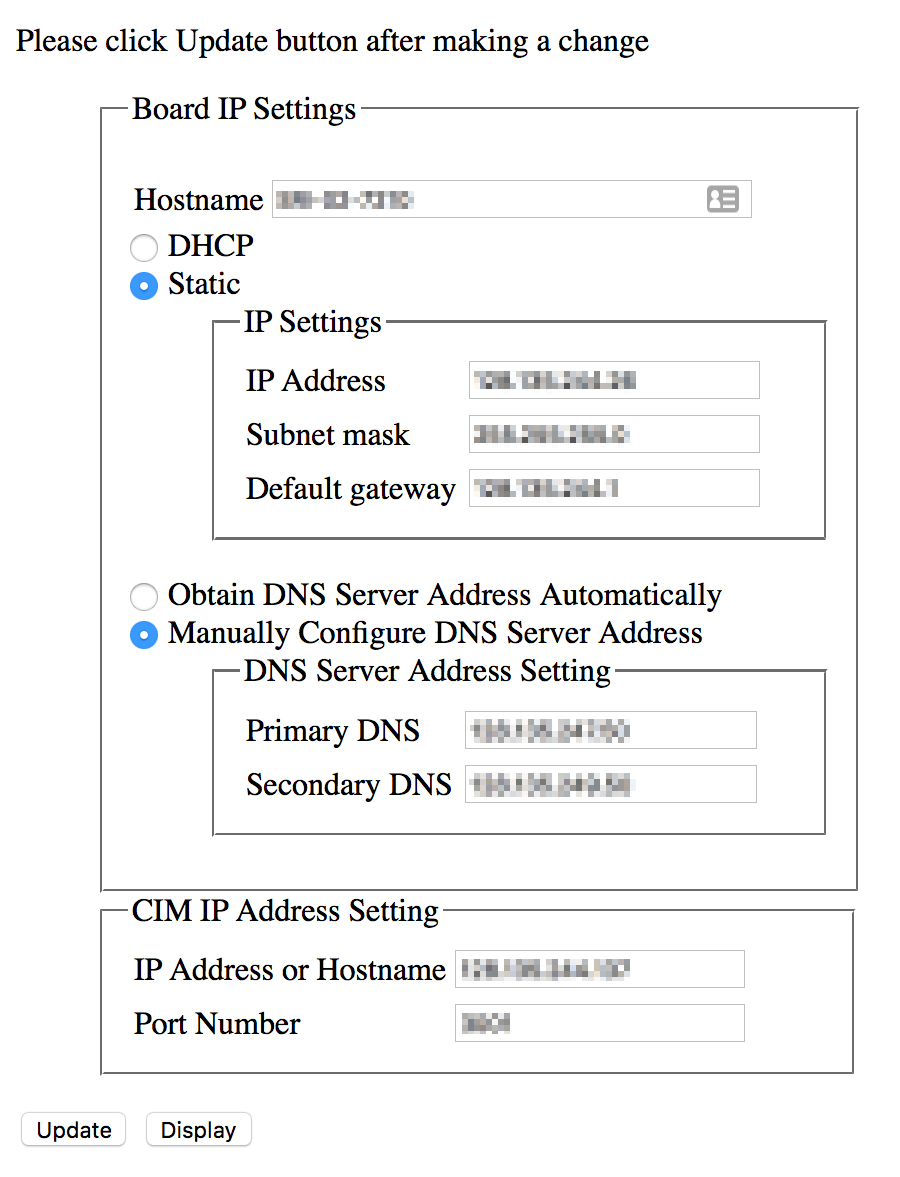

Other printers were found to be printing sensitive administrative documents, including University financial information, University of Chicago Police Department (UCPD) operations plans, and what appear to be UCPD suspect reports. Anybody online, including people without access to the University’s network, could connect to these printers.

Other “Internet of Things” (IoT) devices (physical devices with network connectivity), including cameras, sensors, and even appliances, were discovered to have been left accessible and sometimes controllable. These include several of the Oriental Institute’s cameras, likely meant for security monitoring, which potentially could have been shut off via an online control panel not protected by a password.

The University released a statement last week in response to The Maroon’s findings.

“The privacy and security of University information always has and continues to be of the highest priority,” it read. “As such, the University has a robust security program that is continually tested and supervised. As with most large organizations, occasionally the University’s Information Security office receives reports of potential network, system, or service security concerns. In such cases, the reports are quickly reviewed and investigated and any security concerns that are uncovered are remediated.”

The statement then went on to address whether protected health information was at risk.

“The University conducted an analysis of the information reported by The Maroon, and based on the investigation, has not found any indication that any protected health information could be publicly accessed. The University will continue its investigation of the matter,” it stated. “When the University finds an instance where private information has been breached or disclosed, it begins a process to determine if a notification to the affected population is warranted. Aside from such instances, to safeguard the institution and members of the UChicago community, it is the general practice of the University not to comment on any specific findings, legal conclusions, or remediation steps.”

When asked repeatedly whether “publicly accessed” meant publicly accessible to the general public or more specifically accessible to a person with some technical expertise, Assistant Vice President of Communications Jeremy Manier declined to elaborate and deferred to the original statement.

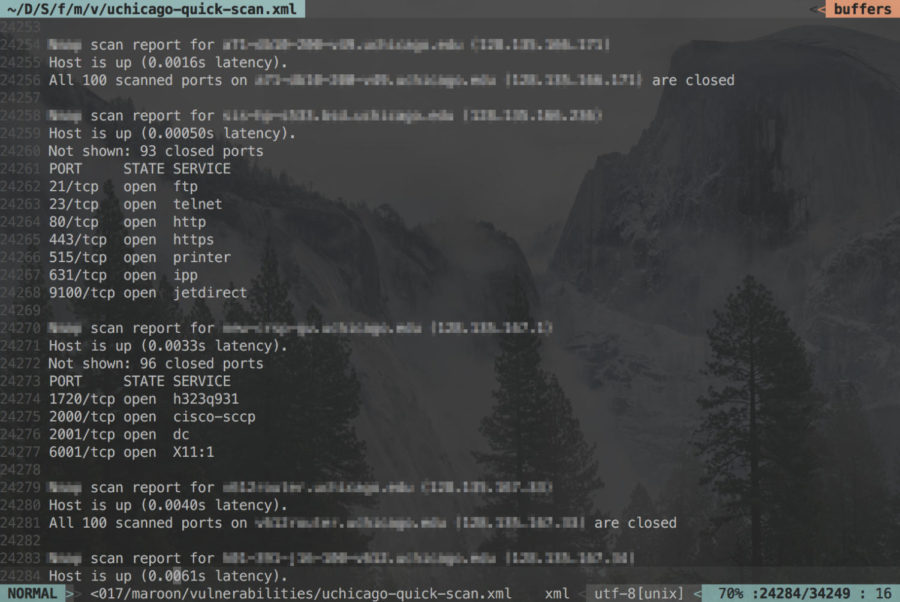

About a month ago, an individual, who wished to remain anonymous for fear of retribution, was contacted by The Maroon after privately saying that they had made some interesting observations after scanning one section of the University network with a free program widely used by both hackers and security professionals. The scan, a potential violation of the University’s network acceptable use policy, identified all the electronic devices accessible on one segment of the University network. This source, upon request, provided the logs generated by the program for verification.

After an analysis of the logs both confirmed many of the original source’s claims and uncovered new vulnerabilities, The Maroon consulted University professors Ariel Feldman and Ben Zhao, experts in computer and network security respectively, to better assess the gravity and legitimacy of the findings. On November 3, The Maroon informed the University’s Information Technology Services (ITS) about the vulnerabilities, in order to provide the University with a reasonable amount of time to make the necessary fixes prior to publication.

It was then that the University opened an investigation. Shortly afterward, the original source admitted to ITS that they had scanned the network, and the individual was formally summoned to the Office of the Dean of Students.

At the time of publication, some, but not all, of the vulnerabilities identified by The Maroon appear to have been addressed.

Printers, an unlikely threat

Printers have often been neglected in security considerations, with many otherwise security-conscious users not fully comprehending the capabilities of these devices.

“Just like almost every other electronic device these days, it’s really a little computer, with a general purpose processor running software,” Feldman said. “So if an attacker can exploit vulnerabilities in that software, they can potentially hijack the device and make it run functionality that was not intended to run.”

This neglect has showed, with the printers of many organizations recently being readily exploited by even amateur hackers. In March of last year, Andrew Auernheimer, a self-styled “hacktivist” claiming to combat what he views as “white genocide,” forced thousands of network-connected printers, including those at Princeton University and the University of California, Berkeley, to print out flyers covered in swastikas and anti-Semitic messages.

Earlier this year, a high school student hacked around 150,000 insecure printers worldwide to supposedly “raise everyone’s awareness towards the dangers of leaving printers exposed online without a firewall or other security settings enabled.”

The University may also have encountered problems. The original source reported seeing some printers with unusual, provocative names suggesting that they had been hacked, though The Maroon could not verify the claims.

Researchers have warned that this neglect could be further exploited, arguing that documents being printed, scanned, or copied could also be stolen by malicious actors. In 2012, Columbia University researchers successfully hacked an HP printer and installed malicious software, potentially allowing an adversary to cause the printer to crash and leak out confidential data.

Earlier this year, Ph.D. candidate Jens Müller and his colleagues at Ruhr University Bochum demonstrated that documents could be stolen or modified from several common office network printers by exploiting long-known vulnerabilities or features of ubiquitous printer programming languages like PostScript and PCL. Attackers can find the IP addresses of these printers by simply scanning a network, as the original source did.

Remote printer document theft is a problem when the documents involved contain information intended to be kept private, which seemed to be the case on multiple University printers.

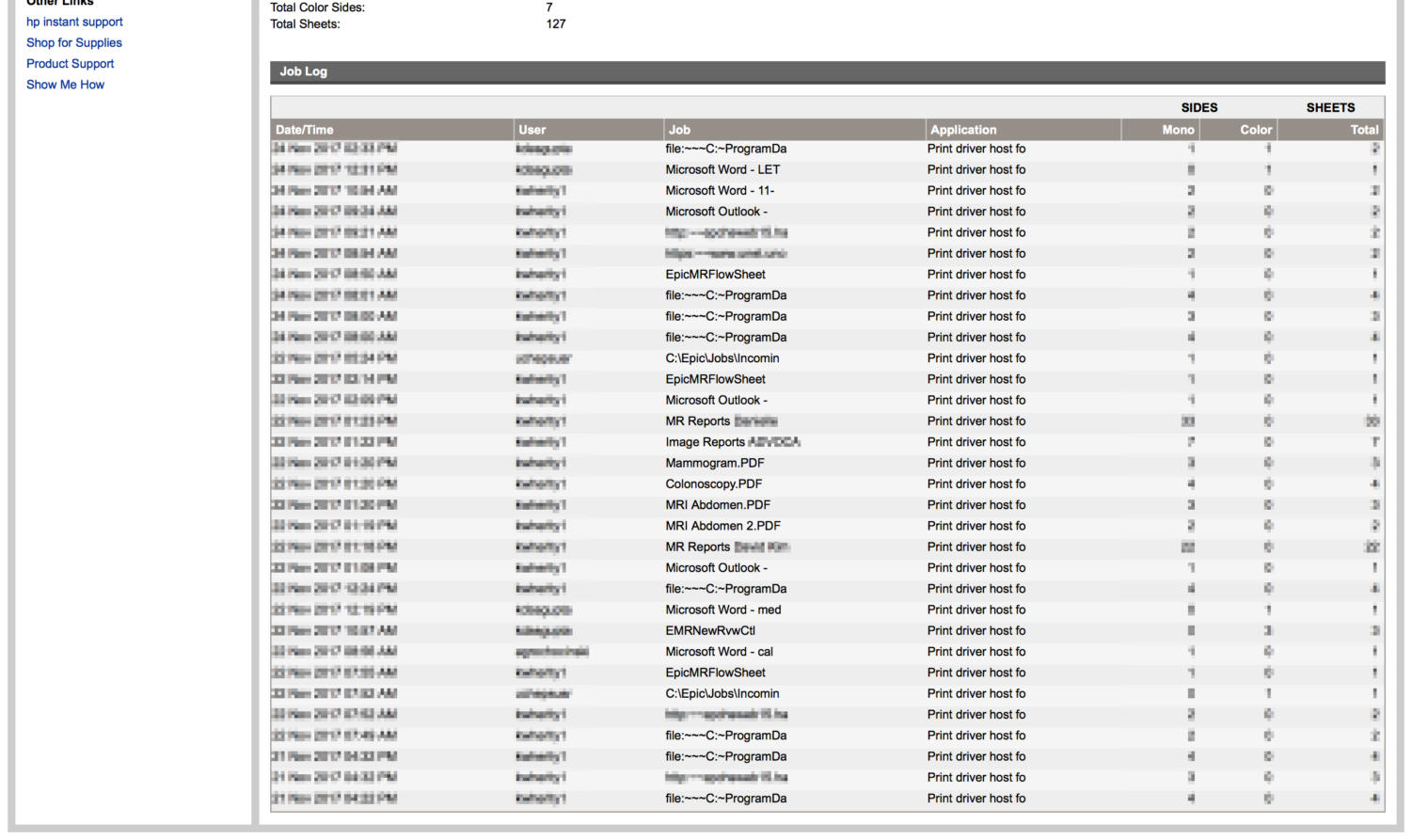

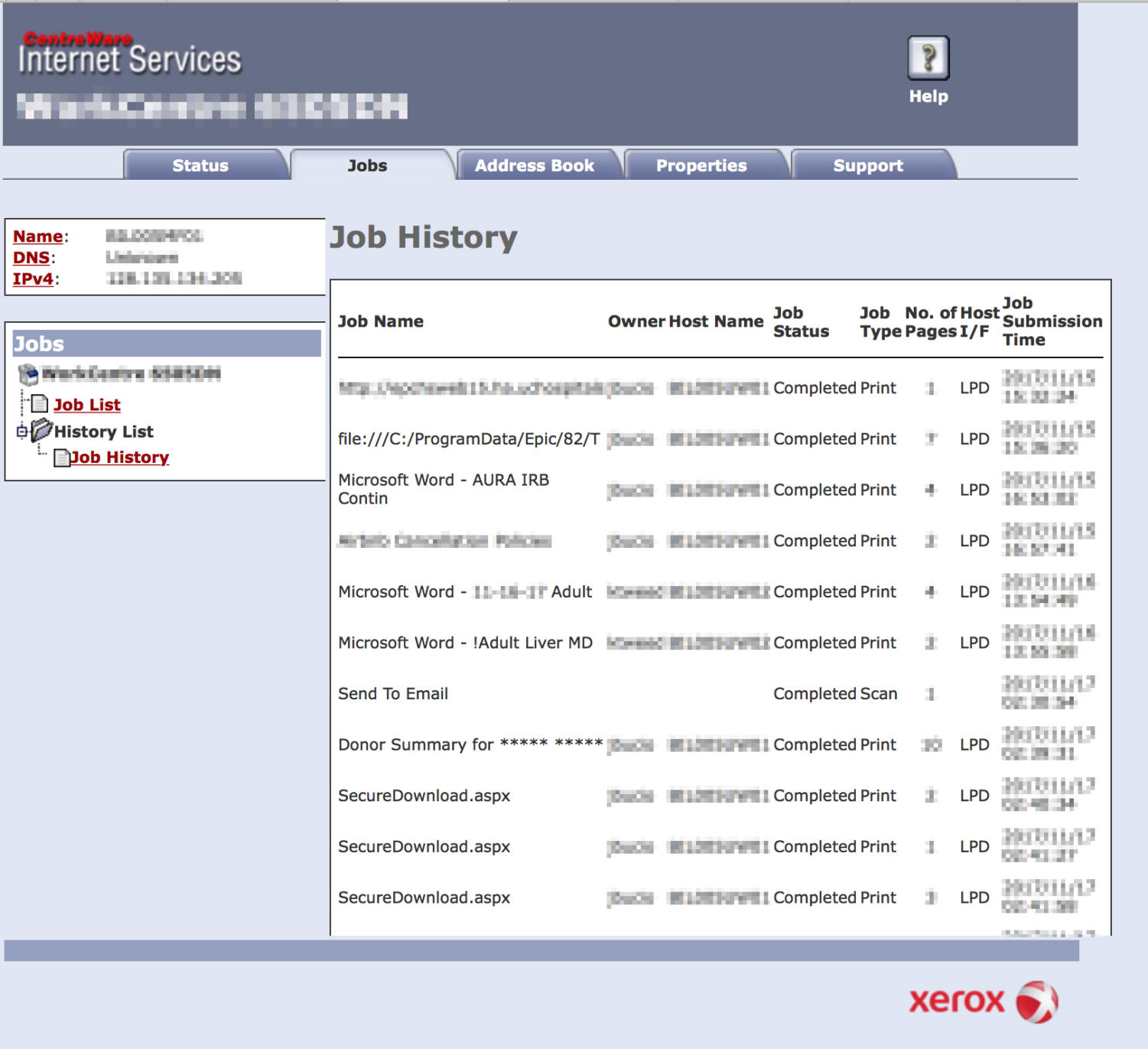

The Maroon found several printers connected to the local network or the broader Internet that had web interfaces and control panels accessible via any browser. Probably unbeknownst to the printers’ users, these interfaces often had unprotected logs detailing print job history—including filenames (e.g. habs_tickets.pdf), the date and time when the document was printed, and people’s usernames—going back a few days.

Several filenames suggested that the file contents being printed were sensitive. Multiple printers were found to be regularly printing files and flowsheets from software from Epic Systems, a healthcare software company that provides, among other things, electronic solutions for storing medical records. Other files were named “Donor Summary for ***** *****,” with the names redacted by the file owner. One registered nurse printed files called “MRI Abdomen.pdf,” “Colonoscopy.pdf,” and “Mammogram.pdf”; another printer had a filename that even included the words “IME set and medical records enclosed,” where IME most likely stands for “Independent Medical Examination.”

In one case, a filename seemed to violate an individual’s privacy all on its own. It included a first name and the words “Topical Pain Rx Form – Ashland Pharmacy,” with Rx a shorthand for prescription, indicating that the file likely contained a prescription for topical pain medication for the individual named. The Maroon found two other cases where a patient’s name appeared to have been included in the filename.

All the printers found to be used to print potentially sensitive health information were only accessible on the University network, meaning that they were, in an ideal scenario, only accessible by students, faculty, and some staff with CNET IDs.

If they contained prescriptions, medical records, and other patient information, these documents could be protected under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996, a law that mandates that, among other things, hospitals “must put in place safeguards to protect your health information and ensure they do not use or disclose your health information improperly.”

Apart from documents containing patient information, a review of logs showed that potentially sensitive administrative documents were printed on printers from multiple divisions. These documents included faculty retention letters and financial updates, including medical staff revenues and surgery funds flows. A UCPD printer, now taken down by the University, was also publicly available; logs showed that it was used to print an operations plan for recent bike thefts, a document labeled “Snell Hitchcock and Bartlett Person of Interes[t],” a file titled “UCPD Arrest Checklist,” and multiple items named “Incident Image.”

All these findings were obtained from examining the relevant printers for only a couple of weeks due to the time-limited nature of the print job history logs. The printers themselves were located in one section of the University network, as The Maroon’s source did not provide network scan logs of the University’s other IP address ranges, including that of UC Hospital System.

As to whether the contents of the files themselves were vulnerable, Müller told The Maroon that he had directly tested a Xerox ColorQube printer and found that he could read its memory and steal printed documents. He admitted, however, that it may not have been the exact model identified by The Maroon, and that many other printer models found on the University network had not been tested.

The Maroon was unable to check whether these printers were vulnerable due to ethical and legal considerations, but documentation from manufacturers showed that many of the printer models found on the University network commonly supported PCL and PostScript. PostScript is “by design,” and in his experience, vulnerable to remote document theft attacks, Müller said.

Either way, Müller suggested that it was reasonable to just assume that printers were vulnerable.

“From all we know, anyone with a decent knowledge and the right tools can break into printers and steal documents if the device is accessible on the network level,” he said.

Müller also noted that print job theft was not the only concern plaguing Internet-connected printers.

“There may be other kinds of attacks besides direct access to print jobs, like denial of service, accessing the printer’s file system or memory, or simply printing a lot of copies or accessing the fax on [multifunction printers]. So, to cut a long story short: Printers really should not be put on the public Internet,” he said.

Feldman agreed that restricting printer access to people logged on to the University network is more secure, but added that this isn’t a panacea.

“An attacker could take over a machine on campus,” he said, and gain access to the University network.

Furthermore, “university networks tend to be more open. It’s probably pretty easy to be granted permission to be on the University network.”

“There are lots of visitors going in and out of the University at a time, there are lots of outside collaborators,” Feldman said. “It’s not really an environment where you can impose tight control.”

Other IoT devices like cameras, accessible and controllable

Apart from printers, several cameras had their video feeds visible to anyone on the Internet. Most of these cameras were positioned outdoors or near entrances, such as in front of the Regenstein and Crerar Libraries and overlooking the science quad.

Though it was unclear whether these camera feeds were meant to be public, an anonymous source who had scanned the network said that they had noticed that the cameras were, in some cases, only guarded by default passwords set by the manufacturer, which are freely available in online databases. Entering a default password would thus allow any individual to remotely control the camera. The Maroon was unable to verify this source’s claim again due to ethical and legal considerations.

In the case of the Oriental Institute (OI), the camera feeds appeared to be inaccessible, but a couple of control panels possibly controlling some of its Internet-connected cameras were publicly available. Each control panel, which may or may not have been connected to an active camera, potentially allowed an individual to change the settings of a camera without a password so that its feed could be manipulated or even made inaccessible, effectively shutting it off.

The purpose of the OI cameras potentially linked to the control panels could not be definitively determined. The panels indicated, however, that the potential cameras were likely manufactured by Shenzhen Sricctv Technology, a Chinese company that makes IP cameras meant for video security monitoring.

After being notified by The Maroon of these control panels, the University quickly made these panels inaccessible. Its reasons for doing so were not given on the record.

Many other IoT devices, such as temperature sensors, were also publicly accessible on the University network. In one case, another source, who wished to remain anonymous for fear of retribution, also scanned the University network and reported finding a coffeemaker that they could control to remotely brew coffee.

Like printers, these devices, when accessible on the public Internet, are easily exploited.

Hackers can scan the entire Internet using widely available programs to find vulnerable IoT devices and exploit vulnerabilities to hack them. These devices then commonly become part of what are known as botnets—groups of Internet-connected devices controlled by a single actor. These botnets are usually used by cybercriminals and government-sponsored organizations to send spam and perform distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks, such as when the Mirai botnet rendered major sites like Twitter, Netflix, and Reddit inaccessible after successfully taking down the Domain Name System provider Dyn.

While The Maroon could not verify whether the devices themselves were compromised due to ethical and legal restrictions, it did find what appeared to be a hacked Windows server used to control IoT devices, among other things, which automatically tried to download and install multiple computer viruses on any connected victim machine. One of the viruses would turn a compatible victim machine into a miner for the cryptocurrency Bitcoin, which is another use-case for botnets.

Like with printers, many of these threats can be reduced by only providing access to these devices to users on the University network.

The challenges of university network security

Both Feldman and Zhao said that vulnerabilities with printers and other IoT devices like cameras were likely to be common at other organizations across the country and the world. Feldman also noted that university networks are particularly challenging to secure, as they are open, permissive, and also decentralized.

“ITS has a very difficult job,” Feldman said. “There are many different organizational units within a university… Faculty don’t like getting told what to do and have a degree of independence from the central administration that regular employees of a company wouldn’t have.”

Because of this independence, it is difficult, if not impossible, for ITS to assign technological equipment to faculty members that they could easily secure, Feldman said. ITS has to figure out ways to secure many different technologies, whereas companies often restrict technology options to make device security more manageable.

“It’s just a difficult balancing act. It would be much easier if there [were] an all-powerful IT administrator who could tell everyone what to do,” Feldman said.

With the rise of IoT devices, University IT departments must secure even more devices while still facing the challenges of the open and decentralized nature of university networks.

When asked whether the tradeoff of having a more permissive, decentralized network over a more secure one was worth it, Feldman said it probably was.

“There are very good reasons why universities are open and decentralized, and I don’t think that trying to impose centralized control in IT or other areas is likely to be successful or desirable,” he said.

“That said, there’s always room for improvement.”