Since winning their respective elections, the University’s two newest unions have both been tied up at the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), engaged in legal fights with the University over election conduct and employee status. Two new Trump appointees are widely expected to rein in campus organizing, but the ultimate outcome for both unions is uncertain.

After winning its election in October, Graduate Students United (GSU) has been fighting a University argument which claims that its members lack the appropriate status to form a union.

The Student Library Employee Union (SLEU), which won its election in June, faces objections to the election’s timing and conduct, as well as questions about the temporary status of its workers.

Established in 1935, the NLRB is a five-member board that oversees unionization campaigns and protects the collective bargaining rights of unions. In particular, the NLRB has full authority to decide who counts as an employee under the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), which allows them to unionize.

However, according to Martin Malin, a professor at Chicago-Kent College of Law, the Board is prone to ideological swings, often reversing its own decisions as to whether a specific group, such as graduate students, can form a union.

“The NLRB tends to overrule its prior precedents much more frequently than courts do,” Malin told The Maroon by phone. “It’s largely become understood that when there’s a change in administration in the White House…you’re likely to see a lot of overruling.”

President Trump has appointed two new members to the board, Marvin Kaplan and William Emanuel, giving it a Republican majority. The new members are expected to overrule Obama-era decisions expanding the power of unions.

Graduate Students United

Graduate students at public universities have had the right to unionize for decades under many state labor laws, although not all have done so. Until the formation of a union at NYU in 1999, private universities, which are governed by federal law, had never seen a graduate student union.

The Board ruled in the Columbia University case last year that graduate students can unionize, prompting a flurry of organizing campaigns at private universities.

Since the decision, the University of Chicago, Tufts, Brandeis, American, the New School, Yale, Columbia, Loyola University Chicago, and Boston College have all seen graduate students vote in favor of unionization.

However, the Board has ruled against graduate unions in the past. William Herbert is a distinguished lecturer at the City University of New York, Hunter College, and the executive director of the National Center for the Study of Collective Bargaining in Higher Education and the Professions. He says that in the Brown decision in 2004, the board was persuaded to rule against graduate unions by concerns over the potential impacts of unionization.

“There have been certain issues that have gone back and forth like a pendulum,” Herbert told The Maroon by phone. “Before Columbia, there was the Brown decision, which Columbia overturned. Brown overturned the New York University decision, which found that they were employees, and the New York University decision reversed earlier decisions.”

As a result, graduate unions may face a precarious legal future under President Trump’s NLRB.

“Folks are generally figuring it's likely that once President Trump’s appointees settle in and they get the case, they're going to reverse Columbia and go back to Brown,” Malin said.

However, a reversal is far from determined. One wildcard is board member Marvin Kaplan, who was appointed by Trump in June. Since his wife works for Columbia University, Kaplan recused himself from ongoing Columbia litigation to avoid the appearance of bias.

In a motion filed in October, Columbia’s graduate union asked Kaplan to recuse himself from Chicago’s case as well. The motion argues that a ruling against GSU could affect Columbia, compromising his neutrality.

However, Kaplan’s previous recusal may not be enough to prevent him from ruling on Chicago’s case. If the evidence does not demonstrate sufficient bias, Kaplan may not be required to bow out of other cases.

“[Recusal] is a fact-driven decision,” Herbert said. “The fact that [Kaplan] recused himself involving Columbia University is not a guarantee that he has to recuse himself from any case that may relate to graduate students or higher education.”

Voluntary Recognition: NYU’s Experience

If the NLRB does reverse itself, graduate students can still unionize, but only if an employer voluntarily chooses to recognize them, based on evidence presented that a majority of employees support the union.

New York University is the only private university that followed this process, certifying a union without holding an election. Cornell’s administration committed to accepting a union if it won majority support, but its election was inconclusive, and the union and the university opted not to count challenged ballots that would have settled the issue.

NYU’s union, the Graduate Student Organizing Committee (GSOC), formed in 1998 and won the right to unionize in a 2000 NLRB decision. However, following the 2004 Brown decision, GSOC lost the ability to bargain collectively.

In 2013, GSOC launched an unprecedented campaign to secure voluntary recognition from NYU as an official union.

“There was a series of big protests both at NYU and across New York City,” Emily Rogers, a member of GSOC’s organizing committee, said. “There was a huge effort by GSOC to organize with other labor groups, and New York is a very union-heavy city.”

As a result, the university gave in, recognizing GSOC in November 2013 and agreeing to a contract in 2015. However, since GSOC depends on the administration for recognition, its future status is uncertain.

“[NYU] will always have the upper hand over us in terms of leverage, because it’s possible that they refuse to negotiate another contract,” Rogers said. “They always have more money, resources, and time than we do, but we also know as workers that the university relies on us.”

If the Columbia decision is reversed and a university wants to recognize its own unions voluntarily, nothing will prevent it from doing so at the union’s request. Likewise, some universities have chosen not to file legal appeals against successful union elections.

“The decision as to whether to grant voluntary recognition really reflects institutional values concerning unionization and labor relations,” Herbert said. “There's nothing that precludes the University of Chicago from negotiating a procedure that can lead to voluntary recognition as was done by Cornell, NYU, and the University of Connecticut.”

In a statement, University spokesperson Marielle Sainvilus justified the administration’s choice to continue its legal opposition.

“The University has been clear in their position that graduate students are students first and foremost,” Sainvilus said. “It is believed that a labor union has the potential to affect the University’s distinctive approach to research and education by making crucial decisions on behalf of students by focusing on collect interests rather than each student’s individual educational goals.”

Student Library Employee Union

In legal filings, the University has raised multiple objections to SLEU’s successful union election, which occurred in June of last year. The objections were rejected by the NLRB’s regional director but now await a hearing in front of the full board.

The University has made two main arguments against allowing student library workers to unionize, the first being that library employment is inherently connected to their education. However, experts agree that the Board would likely have to reverse Columbia in order to accept this argument.

“If Columbia is overturned, [the University’s] next step is to argue that for undergrads, this employment is really part of their financial aid package, and that it's not employment under the [NLRA],” Malin said.

The University also argues that library workers are temporary employees, and thus can’t qualify for a union.

“There is case law about temporary employees being excluded from coverage, but that requires proof that the nature of their tenure is limited, and not indefinite,” Herbert said. “Determinations on that issue focus on actual employment practices.”

In legal filings, SLEU disputes the claim that library work is not employment or is inherently temporary, citing past decisions in its favor.

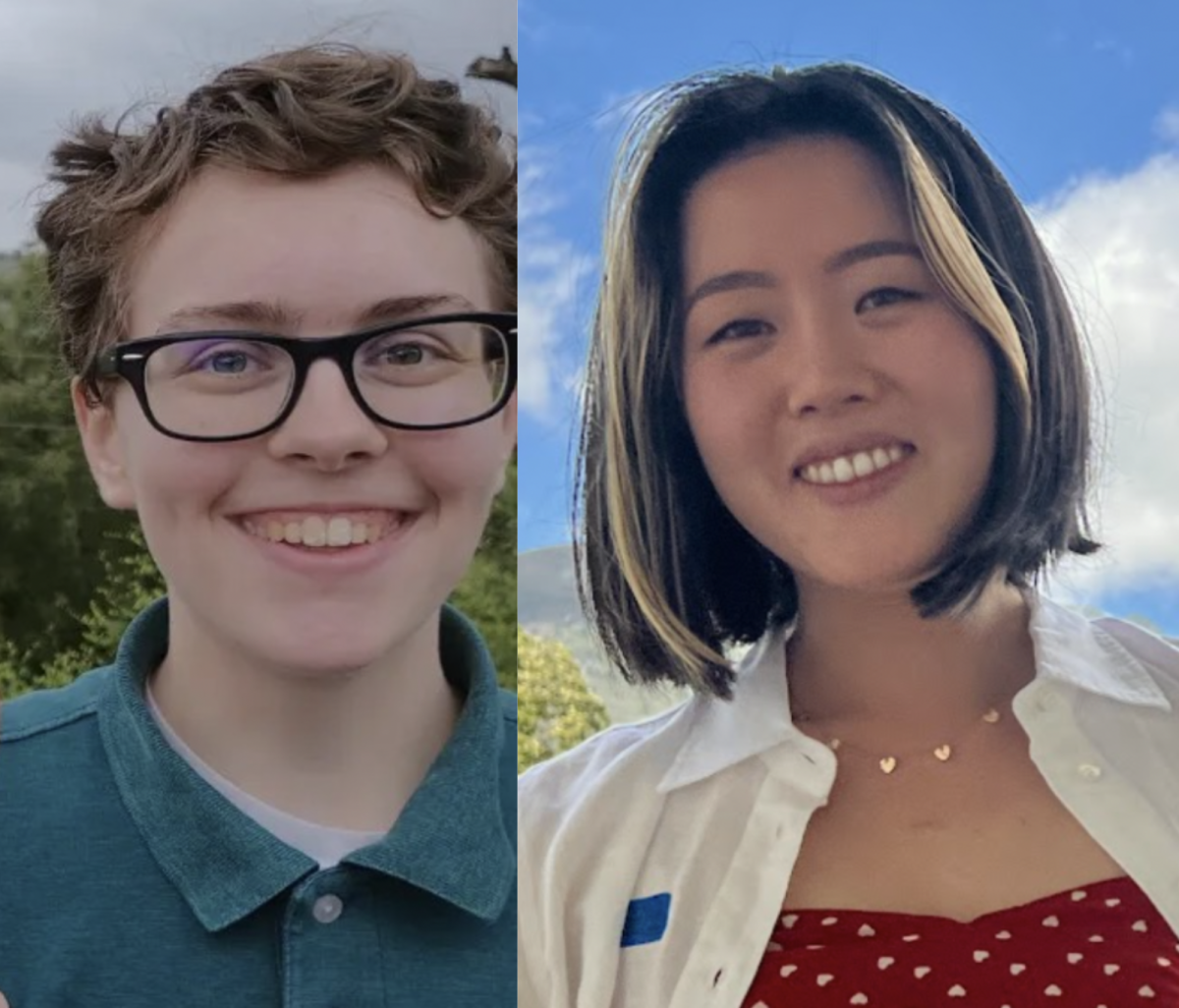

“Our bargaining unit is pretty similar to several bargaining units around the country who have been allowed to organize,” third-year Katie McPolin, a library employee and SLEU organizer, said. “Most of the things the University is filing as objections against us are [aspects] of our bargaining unit that have already been allowed.”

Additionally, the University has raised several objections over the handling of the election. These arguments could justify a new election being held, but wouldn’t prevent SLEU from organizing indefinitely.

In particular, the University alleges that SLEU members engaged in electioneering by talking to voters or standing too close to polls. Similar arguments have failed in the past, but the outcome is far from certain.

“Objections to conduct were also raised in the Columbia case, and after a hearing…rejected,” Herbert said. “It all depends on the facts that are proven."

The University also claims that the timing of the election, during reading period and finals week of spring quarter, biased the result. Sainvilus declined to comment on other issues, but argued that low turnout is evidence of the election’s inconvenient timing.

“The University believes that the regional director’s decision deterred voters from casting ballots,” Sainvilus said. “The overall turnout was less than 40% of all eligible voters, which means that the minority of eligible voters who voted in favor of unionization decided the outcome for all, including for future students who will work part-time in the Library.”

SLEU has responded in legal filings, arguing that since students are required to work during reading period, they also have the chance to vote.

Looking Forward

The board’s chairman, Philip Miscimarra, will finish his term on December 16. The board may grant the University a new hearing before then, but a substantive decision is unlikely.

That means it could be a year or more before the board returns to five members and issues a ruling on the matter.

“Decisions on the merits will likely not be issued prior to the chair leaving,” Herbert said. “Generally, prior decisions are not reversed without a fully constituted Board…it’s probable that within a year or two, these issues will be decided.”

Until then, all parties are in limbo, and bargaining cannot begin.

“Things slow down after the election,” McPolin said. “The election happens, and you win, and then you’re biding your time.”