Editor's Note: Personal narratives and stories were essential to this article in order to tell the full story of the history of sexual harassment and assault on campus. In interviewing survivors, the authors encountered several accusations of sexual harassment and assault that The Maroon ultimately could not verify. For this reason, we have decided to eliminate identifying features of the accused.

“[They] prey on gullibility of white, liberal, young women”

On March 10, 1952, a woman described as the “wife of a Ph.D. student” was abducted from Hyde Park in a car and raped. The story was circulated widely in local papers and within the University community. University chancellor Lawrence A. Kimpton, successor to Robert Maynard Hutchins, wrote that the abduction threw the community into a “near-panic.”

In the 1950s and 1960s, the University experienced a crime wave that increased the visibility of sex crimes in Hyde Park. The University, previously uncomfortable with discussing rising crime rates around the campus perimeter, was forced to acknowledge the increased press coverage and dropping female enrollment rates. While this encouraged the University to take action against sexual assault, it ultimately pushed the University away from acknowledging that, more often than not, such assaults happen within University gates.

In 1952, the South East Chicago Commission (SECC) was formed, which contemporaries attributed to public indignation about the increase of crime in Hyde Park. On March 27, 1952, the new crime-busting commission was established at a meeting in Mandel Hall. According to a 1952 Maroon article, the mission of the new commission was to “drive crime and corruption from the neighborhood in which we live.” During the meeting, Chicago Police Department captain Michael Spatz admitted that prior to the SECC there was little cooperation between police districts, even though, he claimed, many of the crimes were committed by “out-of-Hyde-Park thugs.” Hyde Park crime had risen 32 percent in three years.

“We used a rather sensational kidnapping and rape case to bring the community together and announce a plan for the organization of the South East Chicago Commission,” Kimpton wrote at the time.

The creation of the SECC was not only born from community-wide paranoia regarding the need for women to be protected; it also represented a long-told narrative of the University restricting black migration into Hyde Park. The logic was twofold: keep South Side residents out, and protect the female students at the University.

Following the creation of the SECC, the number of sexual assaults, and the University’s handling of said cases, did not improve. But the dual narrative continued—first, that this was not a campus problem, but a South Side problem. Second, the women of the University had to be more cautious of their surroundings in order to not be raped.

In a 1969 interview with the Committee on University Women (COUW), Richard Moy, the director of health services at the time, cited an incident after Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination where “two girls went into the ghetto to demonstrate their love and solidarity with blacks” and were raped. Moy estimated that between three and six rapes occurred each year. He chalked the frequency of rape on campus to the “blatant stupidity on the [part] of the girl” and “bad luck.”

COUW also interviewed James Vice, the assistant dean of students, in the same year. Vice was responsible for the security reports and claimed that there were only two to three rapes per year between 1967 and 1969, with the exception of a “special problem” at a building in the south of campus that experienced three rapes. Vice told COUW that some girls didn’t want their parents to know about their assaults, particularly if their parents had been “anti-U of C to begin with” and might make their daughters drop out.

He also cited the “occasional problem” with the “pooh-pooh” type that would encourage undergraduate women to walk through Woodlawn at night “so they’ll ‘understand’ the neighborhood.”

“[It] can’t be denied that there are a few hangers-on around campus who prey on gullibility of white, liberal, young women,” Vice said in the interview.

Vice pointed COUW to the orientation training that the University provided to incoming freshmen—much like the Campus Life Meetings the University now hosts during O-Week, in which students are taught about safety and awareness in Chicago.

“Counseling starts in orientation week: where to walk, not to go and come at night. … But a more conscious effort by women themselves would help the most—in the past few years, the number of stationary guards, foot police, and car police has multiplied. Now there are new, white telephones.”

At the end of the interview, the interviewer noted that Vice told COUW to keep the numbers on rape confidential.

As Vice pointed to the threat of sexual assault as something that lived outside of campus, students during that time tell a different story. One alum (A.B. ’65), who wishes to remain anonymous, described the atmosphere of the College as oppressive to women.

When she arrived on campus in 1961 from a New York suburb, she said that she remembered “all the upperclassmen showing up at orientation—checking us out.”

Men would quickly separate the new first-years into two groups: those who were “girlfriend material” and those who weren’t. Those in the latter group would often be taken advantage of, invited to fraternity parties with the expectation of sex.

“I remember younger [fraternity] brothers would invite me to something, but then I would just be taken up [by the brothers] somewhere to somebody’s bedroom,” the alum said. “I was avoiding [sexual assault] by giving in and keeping myself safe that way.”

Younger brothers would “deliver” her to older, often wealthier, brothers. She detailed other hostile encounters with male students, including an incident in which she was kicked out of a fraternity house at 3 a.m. and forced to find her way home.

Throughout all of this, she said that she felt completely isolated from other students, especially women. Part of this had to do with the fact that she placed into sophomore classes and felt out of place speaking to her freshman housemates who were meeting in study groups for classes she wasn’t taking. But she also mentioned that she felt intentionally isolated from other women; there were no all-women support groups at the time, and she can hardly remember other women at attendance at other social events.

“I have no memory of other women being [in fraternity houses], which makes no sense,” she said. “All I remember is the men. I do not remember other women. I think we were really isolated from each other.

“The things you read about fraternities and rape culture today were in place then,” she added.

Yet, despite an oppressive atmosphere on campus, University officials focused on threats beyond campus walls. The alum said she was made very aware of “hazards in the neighborhood” and that one of the major issues for the University at the time was the “possibility that local people from the nearby neighborhoods [would come] into Hyde Park.”

“We no longer see a guard as a restriction on our freedom”

In the 1970s, the University community continued its focus on possible threats from the local community. After a rape in the basement of Snell Hall by a non-affiliate of the University in April of 1973, student groups began to call for armed guards to be stationed within the residence halls.

Unlike cases of student-on-student violence, the University was quick to publicly respond to the Snell Hall assault. In the month after the rape, the University held a public panel to discuss security concerns on campus. Though the locks were changed in Snell Hall, campus security officials decided that armed guards in residence halls were not the right course of action and that a “large, well-trained, highly mobile force,” was sufficient to protect students from crimes. However, students persisted in calling for increased security.

“Students’ attitudes about security have changed since 1968. We no longer see a guard as a restriction on our freedom. Now we recognize the need,” a Snell resident said at the forum.

The resident who was raped in the dormitories wrote to The Maroon in the week after the forum, accusing the University of negligence on the part of the housing system and the security office.

“I will readily admit that it is impossible to absolutely guarantee safety in any building on this campus, particularly if we do not wish to go back to the old days of ‘hours’ and ‘bed-checks.’ However, given that the University has some responsibility, one would assume that it would go to some expenses to make things very difficult to enter a dorm illegally,” she wrote anonymously in 1973.

“The idea of sexual harassment wasn’t invented yet”

There was even less support for those who experienced sexual assault outside of the standard narrative of forcible penetration. As Clover Carroll (A.B. ’75) noted, sexual harassment was simply part of the culture at the time, and women were expected to tolerate it.

“It’s hard for you to understand, but the entire culture at that time supported [sexual harassment],” she said. “So people just didn’t talk about it because it was a part of life for a pretty girl. That’s just what happened.”

Carroll transferred to the University of Chicago from George Washington University in 1973. Having never left home before, she said that she was “in over her head” when she arrived on campus and called herself almost “pathologically shy.”

To try and find her footing at her new school, Carroll immediately joined the choir and signed up for voice lessons. Her mother was a singer, and she herself had sung all her life.

She didn’t know that her first voice lesson at the University would also be her last.

“I can picture the whole situation, I can picture the room and everything,” Carroll began.

Halfway through her one-on-one lesson, her music professor began to fondle her. Unsure of what to do or say, Carroll stood there, paralyzed.

“I’m sure I didn’t say anything to him or push him away,” she said. “What I did was leave after it was over.

“I never sang again, I quit the choir, I never told anybody, I was so ashamed and scared that I never did anything about it. I didn’t tell anybody—not even my friends.”

For years, Carroll struggled to call what she faced an assault, instead blaming the incident on herself. Shame eventually gave way to anger as she realized she lost the one thing that mattered to her most—singing.

“It’s just so sad that I didn’t sing throughout those years,” she said. “I just dropped it because I was so freaked out. It was really tragic in a way.”

The general silence around sexual assault Carroll pointed to continued well into the 1980s. In an e-mail to the Maroon, an alum who was at the College from 1982 to 1988 said that although there was no conversation on the reality of campus sexual assault, there was a significant emphasis on campus safety.

“Students were warned [on a] number of occasions to be careful when we were walking around outside at night. But among us students, there was never any discussion that I can recall about sexual assault.”

Michele Beaulieux (A.B. ’82) recalled a similar emphasis on neighborhood crime.

“There were definitely more boys than girls at the University, and one of the reasons was because parents were reticent to send their girls to the urban, South Side campus,” she said.

A fellow student pressured her into a romantic relationship and subsequently raped her in her dorm room. She told no one.

“I cannot tell you now when I really realized it was rape,” she said.

In what she calls an incredible form of irony, it was the man who raped her who taught her how to defend herself when walking the streets of Hyde Park at night.

“I remember him showing me how to protect myself by putting my keys between my fingers,” she said. “Which is just so ironic to think about now.”

The Origin of Security Alerts

The Jeanne Clery Disclosure of Campus Security Policy and Campus Crime Statistics Act, known as the Clery Act, was signed into law in 1990 after the high-profile rape and murder of a Lehigh University student. Colleges and universities receiving federal aid are now mandated by the Clery Act to publish annual security reports, maintain a public crime log, release “timely warnings” for threats that pose a continuing threat to campus communities, and keep an archive of the past eight years of Clery crimes.

These requirements, however, only extend to “Clery geography.”

Clery geography can be broken down into three categories: on-campus property, non-campus property, and public property. Crimes committed external to Clery geography, on public property, are not required to be included in security alerts.

Sometime after the Clery Act became law, Leah Harp (A.B. ’92) and Alix Burns (A.B. ’93) decided to restart the Womyn’s Union at the University of Chicago. They thought they were creating a general space for women to come together and communicate with other like-minded women about important issues of the time, such as sexual health, sexuality, and relationships.

“It was a social group to create a place for women to come together,” Harp said. “We had a lot of potlucks and fun social stuff.”

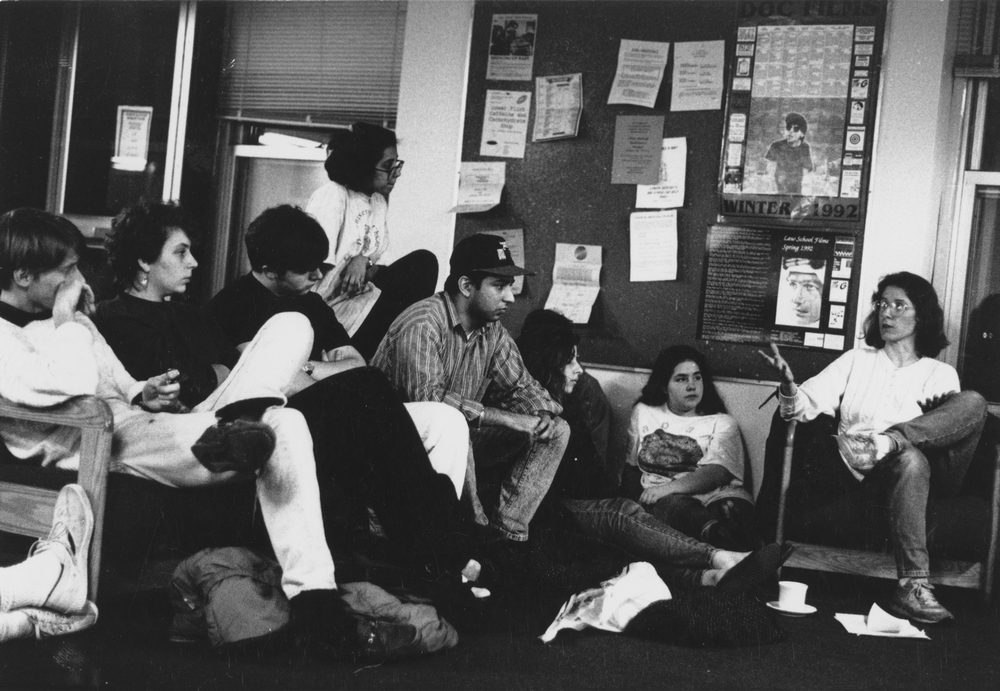

However, in 1992, the group began advocacy work after administrative silence in the wake of a widely-publicized assault, in which a student was abducted while walking down 57th Street between South Woodlawn Avenue and South University Avenue. The victim told police that she was forced into a car and driven to an abandoned building west of Hyde Park where she was assaulted by at least two men. She eventually found her way back to campus when she was able to stumble across a #55 bus stop.

She wasn’t the only one in danger that night. Another student reported to the University of Chicago Police Department (UCPD) that she was being followed while walking up East 57th Street. Her descriptions matched those given by the abducted student, and Jonathan Kleinbard, vice president for University News and Community Affairs at the time, confirmed to the Maroon that it was “very possible it was the same guys.”

Despite the fact that the 1992 abduction took place on campus, only two blocks from the Regenstein Library, no security alert went out. In fact, up until this incident, the University had not sent out any security alerts whatsoever, instead reporting general crime statistics each week in The Maroon.

Information on particular incidents would be spread only by “word of mouth,” according to Burns.

Shortly after the Maroon covered this abduction, the administration sent what was perceived to be a confidential memo to housing staff, informing them of the incident. There was no word on whether or not the RAs and RHs should share that information with students or not.

The administration eventually apologized for its handling of the case, but students unanimously pushed for reforms to the way that the University informs the student body on incidents of crime.

“We, both men and women, must be informed about the incidence of crimes on and around campus,” wrote first-year graduate student at the time Ellen Foley in a Maroon Letter to the Editor. “Whenever something like this happens, we need to re-evaluate our behavior and make sure that we are doing everything possible to protect ourselves. Without easy access to pertinent informations, however, how can we?”

Assistant Dean of Students Martina Munsters defended the University’s silence on the incident, saying that they didn’t inform the campus for “security reasons, to keep things as quiet as possible, so as to not hinder the investigation, [and] the student, herself, wanted to keep this incident as quiet as possible.”

Yet, as other students pointed out, it was possible to send out the information in a depersonalized way, without compromising the identity of the survivor.

“The University, by not warning the community in at least general terms that a horrendously violent sexual crime was perpetrated a mere two blocks from the library, is ignoring the general welfare of its members,” Foley wrote.

Harp, Burns, and the rest of the Womyn’s Union held a candlelight vigil in sympathy with the survivor on February 18. The event, which was well-attended by the campus community, was intended in part to protest in favor of University compliance with the Clery Act, pushing administrators to come up with official procedures for crime notification.

“The outcry wasn’t just [that] the student was abducted and assaulted, it was that the University had deliberately suppressed it,” said Christine Fair (S.B. ’91, A.M. ’97, A.M ’97, Ph.D. ’04), an alum who was on campus from 1987 to 1997.

Ten days later, the University instituted the student-faculty Crime Notification Task Force, which was responsible for making recommendations to the University on what crimes to report on, how, and to whom.

“I admit that we have no guidance on matters of [crime notification],” said Provost Gerhard Casper to a Student Government meeting on security. “In the past, we have unconditionally, I think, relied on [The Maroon] to get out information. The Maroon is not an organ of the University. That is why we have appointed the task force to address this issue.”

The task force called for a formal system to distinguish what crimes call for an immediate security alert. If and when alerts are sent out, they should detail the location and nature of the incident and the relationship of the victim to the accused. Additionally, alerts should be spread through campus-wide bulletins as a way of spreading the information publicly.

“Our concern was not neighborhood crime, but [that] when something happens we should know about it so we can have the choice whether we want to change our behavior in any way,” Harp said. “Providing information was essential so we could then utilize it to make choices for ourselves. It was just another tool for a human living in this space that [they] could choose to utilize or not.”

Students also pushed for an expansion of the umbrella service—a program in which UCPD would help students safely reach their destinations—in addition to increased foot-patrol coverage by the UCPD and University-subsidized self-defense classes.

These additional services, according to an alum (S.B. ’95) who wished to remain anonymous, were essential to many women on campus who felt like there was little to no administrative interest in female safety. She said that before the University implemented its van service in 1992, she would commonly hide in bushes in order to avoid a possible abduction.

“There were a lot of times where I was just walking home from the library, and I would hear a car coming, and hear the music, and [the car passengers] would see me, and they would come back again, and by that time I was already hiding in the bushes. It was a crazy environment. There was no protection.”

An “Oppressively Male” Environment

The University van service and the creation of a standardized security alert system only responded to one narrative of sexual assault. University administrators often did not address the reality of sexual harassment and assault on-campus. According to the 1994 A Woman’s Guide to the U of C, an administrative guidebook for students on women’s issues, “stranger rape,” was the only type of assault accounted for in the University’s crime statistics. Even when speaking of the 1992 abduction, Munsters attempted to comfort the community saying that the incident was the only reported sexual assault of the academic year, “not including date rape and acquaintance rape.”

But as alumni point out, it was these latter two categories women had to worry about the most.

“It was a very male atmosphere at the time,” the ’95 alum said. “We were a population of smart, motivated women, so we managed to get through it, but I can’t say it was an experience that was good for a 17- or 18-year-old woman to go through…. And then [the] University was very male-oriented as well, just in thinking and in lack of protections.”

A 17-year-old girl from Kansas, she came to the University the first year that the dorms became co-ed. She and 11 other first-years lived in the previously all-male Blackstone Hall, which has since been decommissioned.

“In the house of 40 people, there were only 12 girls, and we were all first-years,” she said. “That was strange because we definitely were bullied and basically sidelined, and it turned out that the girls started dating people as a type of protection [against assault].”

Male members would commonly dominate house discussion, telling female members that they were “stupid” and “couldn’t have [an] opinion.”

She also detailed multiple incidents in which she was sexually harassed or intimidated by faculty. On one occasion, in one of her classes in the geophysical sciences division, her professor veered wildly off course during a lecture and began addressing her, the only woman in her four-person class.

“He started talked about how women, when they turn 26, were not viable members of society because our fertility was on the downside,” she recounted. “[The professor said] we were losing our fertility every year after that age. Then he started drawing female reproductive organs on the chalkboard and just went on and on. I felt like I was out of my body. The grad students were taking notes.”

“He came over and was addressing me directly…about my sexuality and my reproductive capabilities. I just got up and left.”

She never went back to the class again. After complaining to her academic adviser about the incident, she was told that he “was not supposed to be teaching undergraduates anymore.” She was not involved in any disciplinary hearings on the incident and was unsure if it was ever really addressed.

“I never had time to wonder what happened to these people that acted so overtly sexual to me,” she said. “They made all these decisions that I wasn’t a part of, and I had to take it on faith that it wasn’t going to happen again.”

She said that her experiences impacted her education as well as her overall mental health.

“If I wasn’t [at UChicago], I probably would have had less stress and a happier social life where I didn’t have to live in this house full of men,” she said. “It would have been a lot better. And I did drop the class, and I generally didn’t go to professors' office hours because it was a whole atmosphere of not feeling safe, and I didn’t feel comfortable being with an adult man alone in the evening.”

“It is not cost-free to call these bastards out on their bastardry”

Prior to matriculating into the College, Fair survived years of childhood sexual abuse by her uncle. Upon arriving on campus, she would have to continue protecting herself from unwarranted advances that threatened her safety.

In 1987, Fair’s first year, she lived in Pierce Hall and was assaulted by a housemate. Though she was able to fight him off, and according to Fair, “[he] did not see coming what [he] actually got,” the housemate continued to harass other women in the house.

According to Fair, her RHs had been let go and not replaced. Fair said that after their dismissals, her dorm became “hyper-masculine,” and the male students in her house would often watch pornography in the house lounge. When Fair needed to report what was occurring with her housemate and the other men in her house, she could confide in no one.

In the 10 years Fair spent on campus while working toward her bachelor’s degree, two master’s degrees, and doctorate at the University, she encountered over five members of the University faculty who were known sexual harassers.

Fair often spent late nights in Searle Chemistry Laboratory. Studying in Searle, Fair listened in while a prominent chemistry professor celebrated his tenure by not only ordering palettes of sushi but also inviting strippers to the celebration.

Fair recollects her supervisor “boasting” about a phone call with then-University president Hanna Gray, who expressed concern over the strippers in the laboratory. The supervisor joked that he was “sorry he missed [the strippers],” as he had been on a trip.

The tenured professor was also known among chemistry students for slipping pages of Playboy Magazine between two flat-bottomed flasks used for cooling dishes in the laboratory. While students conducted their experiments, they were forced to look at images of naked women.

Fair’s second encounter with sexual misconduct on campus was with a distinguished professor of one of the classes that she found most difficult while at the University. Fair remembers being harassed when she would try to get help from the Teaching Assistant (TA) during office hours. When she would enter the room for office hours with the TA, the professor would yell out to the TA, “Your admirer is here!” The professor would joke about this frequently.

“It just crept up on you,” Fair said, “and it just seemed at some point that all of this ambient harassment was normal.”

After her numbing experiences with the chemistry department, Fair chose to pursue a Ph.D. in the humanities instead of continuing her studies in the sciences.

“I foolishly believed that by leaving the sciences, I was going to be entering a realm that was more hospitable to women, and that just didn’t happen.”

In the fall of 1993, Fair was involved with campus activism, particularly advocating against the Yugoslav Wars, in which rape was being used as a weapon of war. Fair often rode around campus wearing her rollerblades. One blade said, “sexual pleasure is no crime,” and the other read, “rape is a war crime.”

One day, when she rollerbladed to a Department of South Asian Studies class she was taking, she encountered one of her professors.

“As I’m handing my paper to him, he actually asked me whether or not I was looking for sexual pleasure. I didn’t know what to do, I had just changed fields…. I wasn’t in a position to tell him to fuck off. I just remember backing out of his office and feeling my eyes well up with tears of humiliation.”

Fair went to her higher-ups in the department to report the harassment, to which she was told that if she didn’t make it clear that the advance was unwanted, the act could not be punished.

She ultimately finished her Ph.D. remotely, after fighting the professor off her orals committee. Now an associate professor at Georgetown University, Fair has come to realize that her experiences at the University of Chicago were unique to the school.

“Chicago sticks out as a real distinctive exception in terms of the hostile environment particularly for women,” she said.

“For those faculty who are still in the field, speaking out…is still perilous. Because he wields so much power. It is not cost-free to call these bastards out on their bastardry.”

Sensationalizing Sexual Assault

Two widely publicized sexual assaults prompted swift campus backlash in 1997, with students pushing for more widespread security protections. In early December, 1996, a 22-year-old prospective law student was assaulted at the 59th Street Metra station. The assailant held a gun to her back and pushed her onto the train tracks where he then proceeded to assault her.

Weeks later, in mid-January, a student was abducted and assaulted in broad daylight at the corner of 56th Street and Woodlawn Avenue. A security alert was sent via e-mail to the campus.

Between 1992 and 1997, the University significantly increased support systems for survivors of sexual assault. In June 1992, the Class of 1992 voted to use its senior class gift to create the Sexual Violence Prevention Resource Center (SVPRC), a resource connected to the Student Counseling Center that provided information about preventative measures as well as resources for survivors.

In 1996, the University responded to pressure from the Action for a Student Assault Policy (ASAP) and created the Sexual Assault Dean-On-Call Program, a group composed of four female administrators who could respond to cases of sexual assault.

After the two assaults that winter, students wanted more comprehensive sexual violence prevention measures. On February 6, 1997, Student Government allotted $2,000 to subsidize women’s self-defense classes, a program that would eventually be taken over and funded by the University administration.

Students also created a volunteer escort service that ran between Woodward Court, the Reynolds Club, and Regenstein, Crerar, and Harper libraries. Students who felt unsafe could use the service and wait for an escort volunteer to walk them home from the library. The program was in part conceived as a replacement for the 1992 umbrella service, which had to end because it became too popular.

“The umbrella service was such a success that it impeded the police from doing their other duties because they were always taking people back and forth,” Munsters said.

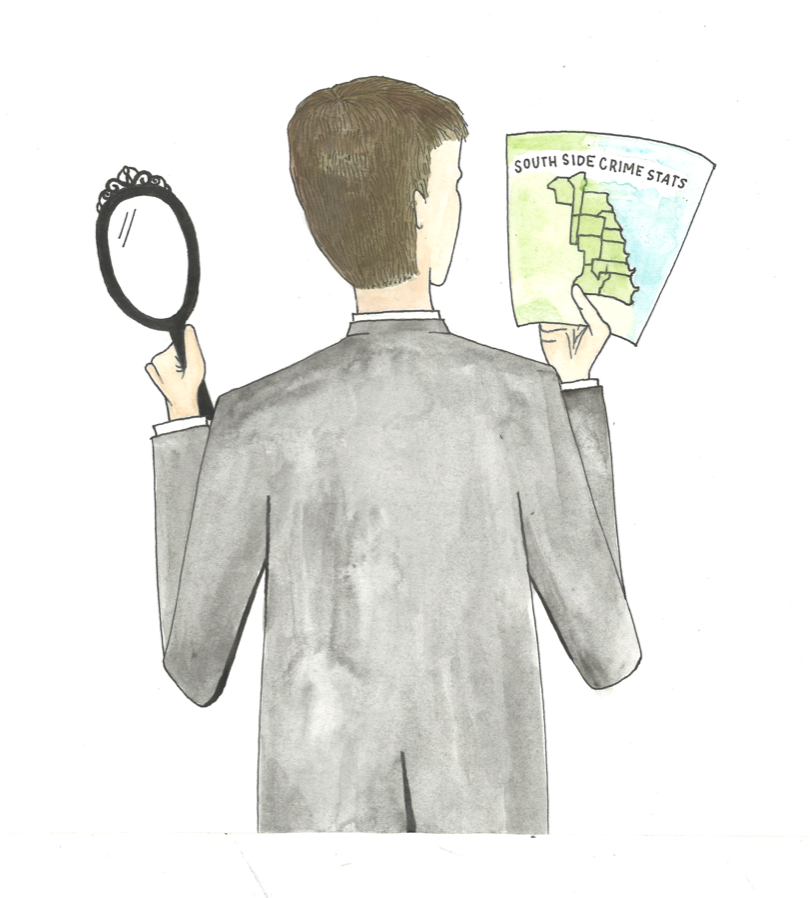

The higher demand from students for more University protections only perpetuated the narrative that the most common type of sexual assault was “stranger rape” and that the University’s position on the South Side of Chicago could mean higher risk of sexual assault.

At least that’s the message Megan Haag-Fisk (A.B. ’00) received when she entered the College. In 1995, she was handed a rape whistle. In the orientation meetings, she remembers that she was taught “how to not get raped” and was told where not to walk on campus. After spending her first year in Burton-Judson Hall, Haag-Fisk recalled that students and administrators would especially caution women against going past the Midway and into the South Side.

“It was sort of like ‘be careful. Be extra careful. You’re crossing over the Midway. You have a little bit of an extra step to be careful of.’”

But the University’s concerted push to be more transparent about the dangers of sexual assault had unintended consequences for the survivors themselves. In Haag-Fisk’s third year, after returning from studying abroad in Barcelona, she was waiting for a friend outside a show in a neighborhood on the north side of Chicago. After her friend’s car broke down on his way to meet her, Haag-Fisk was left waiting on the North Side for her ride back to campus. A man offered to buy her a drink at a nearby bar.

“I had a drink, and that was the last thing I remember. And I woke up the next morning in an apartment of someone I didn’t know with a man I didn’t know in the bed with me.”

Haag-Fisk immediately left the apartment and found the closest phone to call a friend to pick her up and was driven soon thereafter to the University of Chicago hospital, where they performed a rape kit examination.

“I talked to the police, and the city police were fine, they were actually really good. The campus police are who I had a real problem with. They did nothing but victim-blame. And then in talking to the administration, they did nothing but victim-blame.”

Haag-Fisk recalls the Chicago police force being supportive and helpful—they drove around the neighborhood where she was approached and looked at security footage. The Chicago police were able to identify the man who assaulted her and knew he was a predator.

Her experience with campus police was starkly different. She remembers officers asking her “Why would you ever accept a drink from a stranger?” and “What were you doing there alone?” One officer told her that rape was not uncommon for women coming back from being abroad; they became too trusting.

“Coming back [from study abroad] and having this experience was one thing, but then them saying, ‘you need to forget everything you learned in your experience abroad,’ was just very strange.”

A couple of days after her assault, Haag-Fisk remembers standing in the Reynolds Club when she first saw the security alert. In the 1990s, before the age of the e-mail, security alerts were posted around campus on fliers.

“The language was pure victim-blaming. ‘Student accepted a drink from a stranger’—I mean, it was just bizarre for me to see that. That was sort of the trigger for me.”

How has the University’s relationship with the Clery Act changed?

The Maroon sat down with Eric M. Heath, associate vice president of safety and security, to discuss the intricacies of crime reporting, UCPD procedure, and compliance with the Clery Act.

Security alerts are typically sent out when a crime is deemed a “continuing threat” to the community, meaning that the crime may happen again and the University has a responsibility to warn its students. In most crimes that warrant a security alert, police are still actively investigating the incident, and the victim does not know the suspect.

The University is not legally obliged to report crimes external to Clery geography, but, as Heath noted, 75 percent of security alerts emailed to the University community occur outside of Clery boundaries.

“For most Clery crimes, if we do believe there’s a community threat, we’re going to send [a security alert] out. For the other[s], we need to [default] to our guidelines for off-campus incidents, and there’s a very narrow set of parameters where we would send those out. Even if it meets a parameter thing, at times if we don’t feel there is a community threat we won’t send it,” Heath explained.

Heath provided examples for which locations in and around campus would qualify as Clery geography. Residence halls are campus property, and the Arts Incubator is a non-campus property that is controlled by the University for educational purposes, so these buildings constitute Clery geography. The privately-owned Robie House, the fraternity houses that line the perimeter of campus, and student-occupied apartment buildings along East 57th Street do not qualify as Clery geography, and thus crimes that occur at these locations are not federally required to be reported in security alerts.

Heath explained that such examples of sexual assault have not been reported to the Department of Safety and Security (DSS) since he returned to the University in 2015.

Over 50 security alerts have been issued since 2015—only one archived on the DSS's website alerts the community to a sexual assault.

“If we get a report, multiple reports, or even just one report of a suspect date rape, we’d most likely send it out. We just haven’t had those reports, that I can remember in 2016. It doesn’t mean that they didn’t happen, it just means I didn’t get it via [the Campus Security Authority reporting mechanisms], and we didn’t get it via the police department. Could we have those and a security alert be issued? Absolutely. If we don’t know who the suspect is, could we send out a security alert? Absolutely. If we have multiple sexual assaults reported from one specific location, there’s a very good possibility we may send that out,” Heath said.

When cases of sexual assault that occur on Clery geography are reported, the Department of Education requires the University to analyze the reports on a case-by-case basis in order to determine if a community threat exists.

In an interview with the Maroon, Deputy Title IX Director Shea Wolfe added that there is only one scenario in which Title IX and Clery interact—when a crime is committed on Clery territory and the crime is reported to either the University or the UCPD. Under Title IX, safety and security personnel are mandatory reporters, meaning that if they hear of incidences of sexual misconduct in Clery territory, they are required under Title IX to report it to the University. The same goes for the personnel within the Title IX office, who are required to report the crime through Campus Security Authority reporting processes.

Heath noted that the nature of reports of sexual assaults is uniquely complicated, as the victim is statistically likely to know the identity of the offender and is not likely to report the sexual assault to the police department. When reports are filed, Heath added, the DSS must cautiously evaluate whether it constitutes a continuing threat to the community.

“[The known identity of the suspect] creates a lot of different nuances to evaluating whether or not there’s a community threat, and there’s no perfect answer,” Heath said. “We just have to evaluate [the reports] individually and make a determination on whether or not we think the entire campus community can be affected by that particular individual.”

“We take in a lot of considerations, whether it’s victim confidentiality, it’s the wishes of the victim of [the incident] being public, what we know about the individual or the suspect at the time, because that’s the difference in a lot of these cases,” Heath said.

In many ways, Heath emphasized, the University has significantly improved its handling of sexual assault cases. Students during O-Week are introduced to the safety resources available on campus, UCPD officers are trained to better communicate with victims of sexual assault, and rape whistles are no longer distributed during orientation.

When asked about the distribution of rape whistles during O-Week, Dean of Students in the University Michele Rasmussen agreed with Heath that they were largely ineffective.

“When you’re talking about campus sexual assault, it’s students who know each other in a context where a rape whistle wouldn’t at all be helpful,” said Rasmussen.

Heath also pointed out that the annual security report that is required by the Clery Act has been renamed.

“It used to be called ‘Common Sense.’ That’s insulting, considering that the entire book has now evolved to be around sexual assault, criminal sexual assault, domestic violence, dating violence, [and] stalking,” Heath said. “The idea that we’re telling people or insinuating that if you just use common sense, you won’t be a victim of that crime…”

Heath acknowledged that though the ways in which the University has handled cases of sexual assault has evolved over the years, there is still room for growth.

“You ask me, ‘Where do we need to improve?’ I think we just have to consistently train. I think this has to be an annual, if not daily thing, that we’re teaching our officers and training our officers around the misperceptions around these types of crimes and how to respond compassionately to these types of issues. I think, over the course of 25 years, that’s really where law enforcement has failed.”

“I think the University of Chicago has definitely improved significantly what they have done over the past several years, and I think you’re seeing better reporting because of it.”

As revealed by a Freedom of Information Act request by the Maroon, there has been only one Clery complaint against the University of Chicago. The complaint, which dates back to 2013, alleges that the complainant's assailant was granted free access to the dorms—even after her assault was reported to the UCPD.

The Maroon put in a request to see security alerts that were within the required eight years of archiving but were not available via the online archive. Below are the totality of security alerts issued in the last eight years regarding sexual misconduct, harassment, and assault. Photographs and photocopies were not permitted at the viewing of past security alerts. Therefore, those below are reproductions based on thorough notes.

CONCLUSION

But would more security alerts help the University improve its reporting of sexual assault? Heath seems to think that there is no clear solution.

“We get complaints both ways. We either send too much or we don’t send enough. There’s no perfect medium,” Heath explained.

Survivors and activists don’t see eye to eye on the issue, either. In 2012, Michele Beaulieux, the student who was raped in her dorm room, inadvertently reported the assault she endured 33 years after the fact when exploring disciplinary options. There is no statute of limitations for reporting a crime to the police or to the University or for filing a disciplinary complaint at the University of Chicago.

The annual Clery sexual assault statistics released by the University contain the crimes reported in a year, not necessarily the ones that actually occurred that year. Considering Beaulieux’s assault in 1979 occurred on Clery geography, it was included as one of the five assaults reported in 2012.

Official University recognition of Beaulieux’s assault was validating for her, but it also shows the need for clarity about the Clery Act sexual assault statistics.

“The numbers reported and [what] actually happened are different,” she said.

Beaulieux also expressed concern that increasing security alerts focused around sexual assault could promote a singular narrative of sexual assault.

“It would probably end up focusing more on stranger rape,” she said. “There are other things that I would want to focus on more. The problem is that the rapes being reported are not typical rapes. Alerts perpetuate the notion that I’ll be safe if I keep my keys between my fingers when I go out.”

Others argue that reporting more cases of sexual assault in security alerts could inform the student body of their startling frequency on campus. Sexual assault advocacy group Phoenix Survivors Alliance (PSA), met with Provost Daniel Diermeier to discuss concerns with the University’s handling of sexual assault.

Fatima Eldigair, a first-year in the College and member of PSA, asked the provost why security alerts generally do not report sexual assault, saying that it serves as a safety measure for members of the campus community.

“Beyond the preventative potential of security alerts, it raises conversation regarding the reality of sexual assault on campus, and forces UChicago to take ownership over sexual violence that occurs against their students,” Eldigair wrote to The Maroon following the meeting.

In Eldigair’s recollection of Diermeier’s response, the provost both contended that security alerts did not fall under his purview and stressed that the nature of campus-wide security alerts pertinent to sexual assault was “complicated.” The circulation of these reports, Diermeier surmised, could potentially desensitize individuals to the issue of sexual assault.

“I found this to be highly ironic because the University sends us e-mails regarding strings of petty theft and robberies frequently. UChicago creates this racialized narrative that Black Southside assailants constitute a threat rather than student predators. They perpetrate the idea that sexual assault is not a prolific epidemic on our campus through willfully choosing to not publicize incidents of it,” Eldigair wrote.

Though the Title IX office informed her that campus-wide security alerts about sexual assault could violate the survivor’s privacy, Eldigair refuted this concern. Not only does the UCPD publish these reports on their crime log, Eldigair argued, but it is also possible to craft an e-mail without revealing specific information about the victim or the crime.

“If UChicago cared about the well-being of its students, they would inform us about sex crimes the same way they do with robberies. As I see it, the University is compliant in propagating sexual violence through not alerting us.”

Though the University has made significant strides in its methodical approach to handling reports of sexual assault, a dark shadow of its past missteps looms. Each survivor’s story is unique, but there seems to be an overarching pattern of normalizing on-campus sexual assault. For too long, the reality of sexual assault on campus has been obfuscated as the University ascribed an internal problem to the non-campus community.

This case study of the University’s history of insensitivity and mishandlings in its approach to assault is likely a microcosm of a far-reaching problem that extends to other universities throughout the nation, particularly those also located in low-income and traditionally segregated cities.

Students and administrators should recognize that behind the University’s façade of towering gothic architecture and academic prestige lies a dark, deeply-rooted history of stigmatization and maltreatment of sexual assault and harassment survivors. Whether it means sending out more security alerts that report sexual assault or not, it is time to turn the lens inward.