Art rarely exists in a vacuum. It responds to and shapes the political and social context in which it was created. Last weekend, seven artists from around the world gathered in the Logan Center for the Arts to address a weighty question: “What is an Artistic Practice of Human Rights?” Through a multi-day summit that explored issues such as U.S. criminal policies, the refugee crisis, and the hypocrisy of governments, the artists not only formed a community among themselves, but constructed a discourse with the audience.

The summit was proposed two years ago by Mark Bradley, a Bernadotte E. Schmitt Professor in the history department and the faculty director of the Pozen Center. A collaboration between the Gray Center for Arts and Inquiry, the Pozen Family Center for Human Rights, and the Logan Center, the summit featured artists whose work exposes national and international neglect of human rights.

The artists work through a variety of media, including film, performance art, architecture, and activism. Such diversity was important to the coordinators, who wanted to invite mid-career professional artists working on “the edge” of what can be considered art.

“[We hoped] to air away from anyone feeling like a keynote speaker,” explained Leigh Fagin, assistant director of collaborative programming at the Logan Center.

Cinematographer Carlos Javier Ortiz screened two of his films, We All We Got and A Thousand Midnights, on Saturday. The former is an award-winning piece depicting the profound sense of communal loss caused by gun violence in the United States; the latter, an exploration of racial tensions facing the African-American community in the South. Ortiz chose to shoot both in black and white to remove any jarring elements that might interrupt the narrative, like a pool of blood whose “color was too distracting” in the background. His works resonated powerfully in a city where gun violence regularly draws media attention.

“People are lazy,” lamented Ortiz regarding the response of community members to civic issues. “[They] are sleepwalking a bit.”

Zachary Cahill, one of the coordinators of the event and the curator for the Gray Center, echoed Ortiz’s frustrations, but also sees ways art can offer solutions.

“There is a kind of numbing effect that can start to take place. Maybe one of the things that artists can do is take away that anesthetic,” he said, “[to] make some of these stories and issues of human rights much more real and visceral, and get people to connect to other people.”

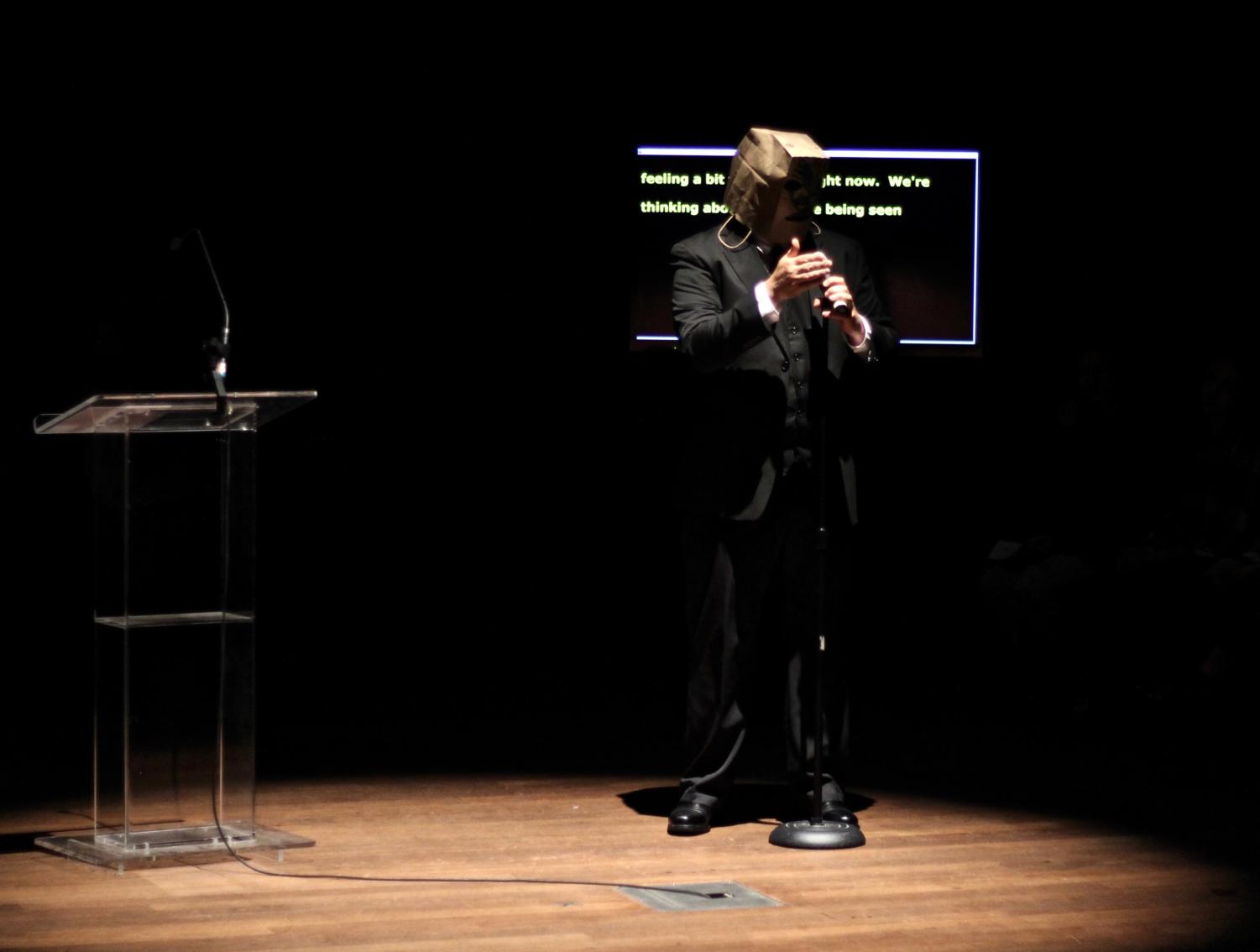

One artist who certainly generated a call to action was Laurie Jo Reynolds, professor at the School of Art and Art History at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Reynolds creates what she terms “legislative art,” centered on policy and social practice. Her presentation was unconventional, yet conveyed an all-too-familiar message.

The stage was set to resemble a courtroom, with a podium surrounded by a half-circle of chairs. People would stand before the podium and give personal testimonials about how the sex offender registry had impacted their lives. The speakers included both sex offenders and sexual assault survivors—often the same person. The mother of a child with a learning disability spoke about her child’s difficulty understanding the guidelines he had to follow as a sex offender, and many adults described constantly having to move in order to maintain the required distance from facilities designated for children.

It is difficult to describe the power of Reynolds’s piece. As speakers shared testimonials and policy analysts explained the problems with the sex offender registry system, the captivated silence from the audience indicated the intense emotional impact of the presentation. Although it was an act, Reynolds’s work conveyed disturbing realism; art was not just reflecting, but also enacting, life.

Perhaps this shock of realism is the force needed to initiate the social change intended through the work. This is not to say that the artists had to forgo aesthetic appeal in order to captivate the audience, or that aestheticism itself cannot be potent, but aestheticism alone might not combat the public’s impassive reaction to human rights violations.

“[I look for ways to] transform effect into political effectiveness,” explained Cuban artist Tania Bruguera. She even addressed the criticism she often receives about her work not being visually pleasing.

“The biggest orgasmic pleasure I had was when I fought the Cuban government,” she countered.

Yet some of the artists argue that even the organization of this public is constantly threatened by the state implementations of authority.

Sandi Hilal, who works with her partner Alessandro Petti to create architectural designs for experimental educational programs in Palestinian refugee camps, communicated the destabilizing effects and “condition of permanent temporariness” created by refugee camps. Yet the sociopolitical chaos created by the camps is not the only battle with which these architects contend; the refugees who use the facilities are often wary of their effect as well. By making permanent a temporary situation, “we are the first enemies of the refugees.”

These architects must constantly “acknowledge the exceptional political situation” and find ways to positively intervene. But because the circumstances of refugee camps are so erratic, attaining stability is almost impossible. In fact, all of the artists on the panel, no matter where they based their work, expressed this feeling of perpetual volatility.

Many of the artists expressed feelings of insecurity in their own homes. Jelili Atiku, a Nigerian multimedia artist, described how the police came for him in the middle of the night so that his community could not protect him. Similarly, the Cuban police interrupted Bruguera’s 100-hour performance of Hannah Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism to detain her for eight months.

In a world that often ignores the intensely political implications of artistic practice, the bond between artists is important. Yet this kinship is rare. As Reynolds stated, “this has been the only collectivity I’ve felt [in the artistic sphere.]”

Through the conversations during this summit, it became apparent that a local or even national artistic community is not enough; the only way to initiate an effective artistic practice of human rights is to transcend nationality and form an international unity. Case in point: these artists found a unique global network through this summit. The future will show what this network will generate.

An exhibition featuring the works of these artists is open at the Weinberg/Newton Gallery, 300 West Superior Street, through June 10.