The Smart Museum of Art’s latest showing, The History of Perception, opened on January 9. More than just an exhibition, however, The History of Perception is course material: The various artistic works on display have been carefully curated by Michael Rossi, assistant professor in the history of medicine, in consultation with Smart Museum Assistant Curator Berit Ness, to accompany a class taught by Rossi this quarter.

Professor Rossi’s class, also entitled “History of Perception,” is cross-listed in the history, HIPS, and anthropology departments, and is now a KNOW class. The mysterious “KNOW” classes—including offerings this quarter such as “History of Skepticism,” “Feminists Read the Greeks,” and “Planetary Britain, 1600–1900″—are offered through the Stevanovich Institute on the Formation of Knowledge.

Located between Alpha Delt and Calvert House, the Stevanovich Institute opened in the fall of 2015 and boasts a prestigious group of faculty and fellows from fields including medicine, history, divinity, anthropology, and literature. This group is united in their commitment to examining the bounds of knowledge, its formation, and its cultural context.

“History of Perception,” as taught by Rossi, is predicated upon the premises that “perception—construed, roughly, as the cognitive ordering of notionally sensual phenomena—has a history…[and] that this history is both constitutive of and constituted by the exigencies of particular political, social, ideological, and institutional orders held by different people in different times and places.” The course seeks to examine how humans have historically understood sensation to be cognizable, and thus, communicable.

It achieves this goal partly through The History of Perception at the Smart Museum. As the introduction to the exhibition notes, “Art acts as an immediate sensory stimulant—a prompt for the viewer to think about the ways sensations and ideas play off one another.” However, in addition to stimulating the viewer as a means of transmitting ideas, “art objects serve as archives of the history of perception, capturing the specific concerns, anxieties, and exultations of a particular place, person, or era.”

As part of the course, “students will be asked to contribute wall texts, performance pieces, pamphlets, maps, soundscapes, or other supplemental material to the exhibit” in order to help viewers consider the subjective concerns intrinsic to each work of art.

Perhaps inevitably, the collection of art on display feels a little disjointed in the absence of student contribution. There is no explanatory wall text conveying the voice of the curator throughout the gallery, which is intentional—eventually, students will be creating the texts. In the short term, viewers are left to fill in the blanks themselves. This reviewer personally felt a compulsion to impose some sort of unifying consistency on the exhibition, which made me question whether walking through the gallery was a self-conscious commentary on perception.

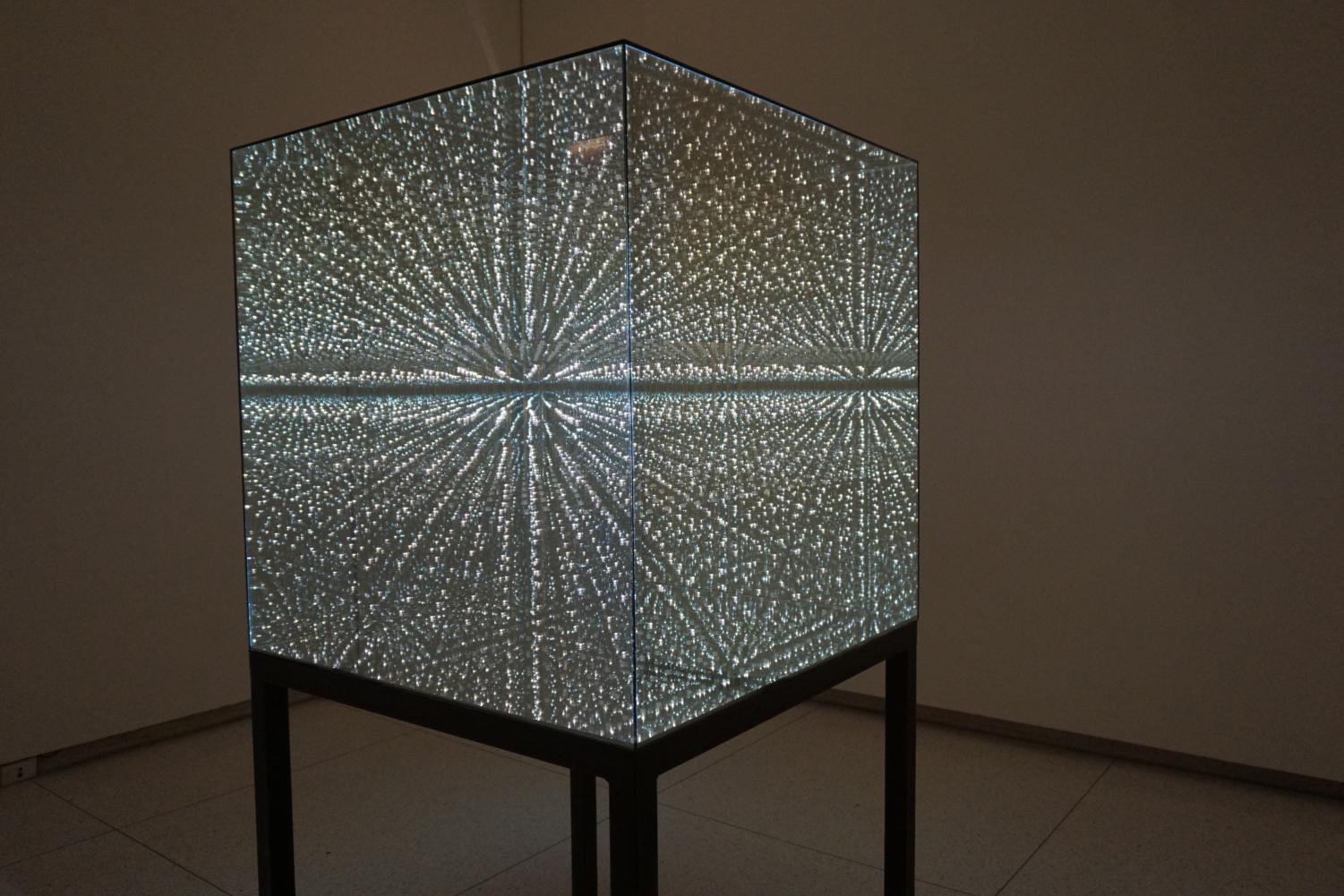

Nonetheless, the art itself is a pleasure. From Dada-inspired works by Jean (Hans) Arp and Dieter Roth, to the installation Light and Space by Robert Irwin, The History of Perception highlights some real gems from the Smart Museum’s permanent collection. If the excitement surrounding Yayoi Kusama’s infinity mirror rooms is any guide, Antony Gormley’s Infinite Cube is bound to be a crowd pleaser. It is a collection of small LEDs arranged within a mirrored cube so that the only thing separating the viewer from a seemingly infinite void of small lights is a transparent glass case.

That said, it is disappointing that the art on display in The History of Perception is limited to European and American art. It is unclear whether that was a curatorial choice, or a result of the limitations of the Smart Museum’s collection. Perhaps works by artists like Hélio Oiticica and Lygia Clark, which require interaction with art objects, could help explore the historical relationship between sensation and cognition from additional perspectives.

Nevertheless, The History of Perception is a worthwhile arrangement of art to wander through and will undoubtedly be enhanced by its engagement with its corresponding UChicago course throughout the quarter.

The History of Perception is on view at the Smart Museum of Art until April 22, 2018.