Last Tuesday, I spent a few hours exploring the Museum of Contemporary Art, including its exhibit on local Chicago artist and contemporary queer icon, Paul Heyer. If you can make it on a Tuesday, go: The MCA is free to Illinois residents and open until 9 p.m. on that day, offering plenty of time to wander and not spend a moment thinking about getting your money’s worth.

Not that you’re likely to waste money if you don’t. The MCA’s upper floor houses an impressive standing collection of contemporary work, organized by style and era along a meandering loop that takes maybe an hour to enjoy thoroughly. Pieces from Andy Warhol and Roger Brown offer star power and the delightful surprise of coming face-to-canvas with something recognizably famous. Work from James Welling, meanwhile, offers hypercontemporary pieces from within the last two years.

The MCA’s Paul Heyer exhibit, however, features only two rooms. The exhibit begins and ends with nine paintings, one model of the universe made out of brooms, and one oversized lamé comforter. At the very least, three of the paintings are pretty big.

I don’t want to be ungenerous toward the MCA; the exhibition is small but not trivial, carefully curated, and well-paired with extensive printed materials. But there is something bitter about discovering the truth behind the advertising. The Paul Heyer exhibit is very small. Do not expect to spend more than 20 minutes in it—which is disappointing, because it’s good art.

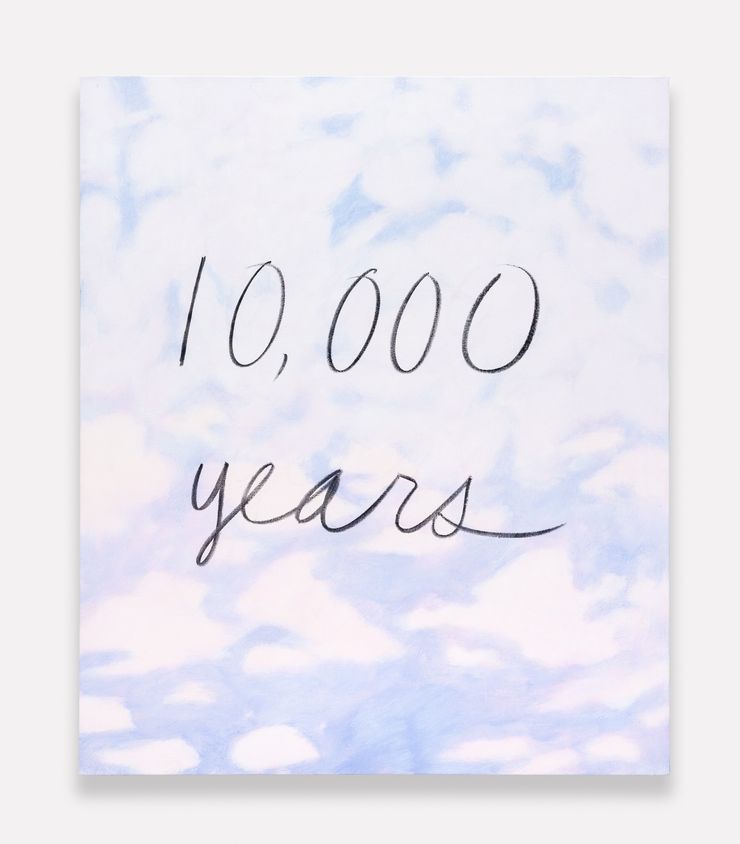

Heyer (born 1982) is a Chicago native and multimedia artist with an MFA from Columbia University whose work examines club life and pop culture through a queer lens. I had to think for a while before I could find the club life, pop culture, or queer references in Heyer’s work—which is to say, the man is no Warhol, and does not paint polemics. But with the helpful guide of the MCA pamphlet, I could parse more. In one work, cursive text (“I am the sky”) on a Taylor Swift–esque cloud background asks us to imagine ourselves as the impossible. Becoming something else is a theme of Heyer’s: He doesn’t paint people but skeletons, saying that he finds them more approachable. Black-stained brooms become a model of the universe. A giant silver comforter is the centerpiece of the exhibit: It asks us to wonder about comfort becoming metal, science fiction becoming comfort, and dreams becoming…something else.

The MCA tries to invite us into this feeling. One of its two Heyer rooms is dark and softened by a dreamy, ambient soundtrack subtly piped in through speakers. It is a surreal, otherworldly experience: Strategically placed spotlights make his canvases glow, and it is tempting to believe that the luminous image is the only thing in the dark room. It doesn’t hurt that Heyer is interested in hyperreality, either. His three largest paintings feature LSD-colorful images over which Heyer has painted opaque white or black circles that seem to obscure and consume what’s behind them, adding a layer of mystery and unavoidable menace. The shrouded and altered nature of the images evokes his queer perspective. For instance, a cowboy, all the colors a human has never been, cups water delicately to his mouth while his body disappears into a white circle. He is masculine and tender and has begun to erode. Heyer might be subtle, but the message is there.

Indeed, one of my favorite aspects about the exhibit was the scope of Heyer’s message. His cloudy backgrounds, overlaid with grandiose demands (another example: “10,000 years,” which the pamphlet said was a request for the viewer to imagine 10,000 years ago, but which I suspect is a demand that the viewer be 10,000 years—whatever that might mean) are soft and airy, but so demanding as to make us wonder what we can reasonably do. The pure, inhuman circles eating into strange but familiar images suggest a malicious element going ignored in the everyday.

Indeed, it seems that being is a central concern in Heyer’s work: being very big or very small, being something and then something else, or finding that being is not what we think it is (such as when what we think is is actually being consumed by scary white circles). Heyer’s work contemplates the vein of sublimity that runs through being, and like the best artists, actually manages to touch it, making his work both vast and miniscule.

Which all makes me wish the exhibit were more of the former.