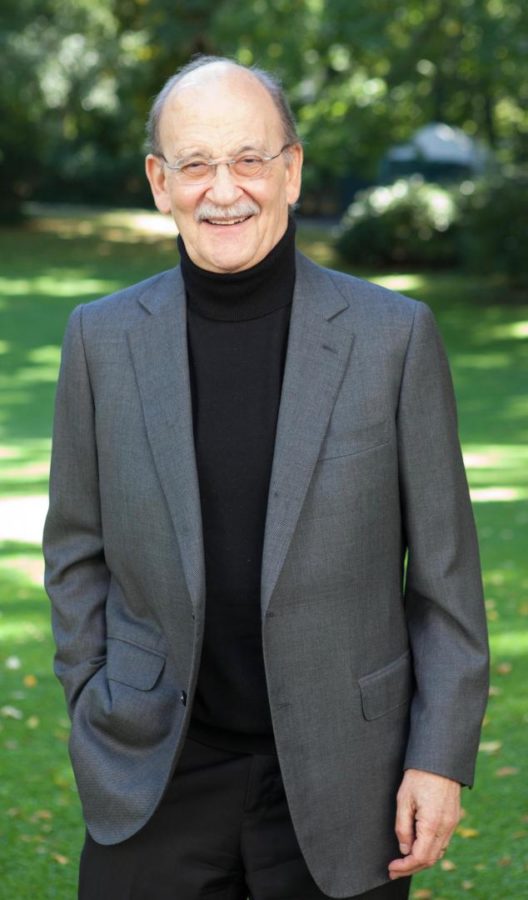

Professor Moishe Postone spoke out candidly about the less than optimistic time the world was witnessing at the Vienna Humanities Festival last November, astutely critiquing the ongoing political and social climate as he had done throughout his career.

“We have reached an age which is potentially as authoritarian as the interwar period, that most of us thought had been left far behind. I think it’s a very dangerous time. The problem is, there is no compelling imaginary of what could be a different future,” Postone told the crowd gathered at the festival.

“Marx is sort of a historical optimist. You don’t seem to share that part of Marxism, do you?” quipped the host, Austrian historian Raimund Löw.

“My analogy is, if you want to understand the significance of a great work of art, you don’t necessarily interview the artist…. If I were writing a biography of Marx, I think I would try to talk about this tension between Marx the analyst and Marx the revolutionary,” Postone replied.

Coming out of the 1960s–70s New Left as one of the world’s leading scholars on Karl Marx, Postone creatively reinterpreted Marx, insisting on the contemporary relevance of the German social theorist’s work. A teacher as well as a scholar, Postone shared his insights with generations of undergraduate and graduate students.

On March 19, 2018, Postone passed away at the age of 75 after years of battling brain cancer. He left behind two unfinished book manuscripts, Capital: A Reading and Critical Social Theory and Contemporary Historical Transformations, according to the history department.

“Capitalism, in making us wealthy, increases human potential, but it does so by yoking us to capitalism’s values, not values by which we ourselves freely choose to live. Moishe believed that even left political movements had become trapped in capitalism's value system,” said U.S. history professor Jonathan Levy (A.M. ’03, Ph.D. ’08), who was Postone’s co-editor on Critical Historical Studies wrote to The Maroon in an e-mail.

Dean of the College John Boyer remembered Postone as a “real intellectual,” concerned not only with the past, but also with ongoing issues in society.

“He had a very lively, creative, and fertile mind, but it wasn’t restricted to simply the 19th century, it was really the late 20th and 21st century in terms of the problems he was trying to deal with,” Boyer said.

Postone’s first and most renowned book on Marx, Time, Labor, and Social Domination: A Reinterpretation of Marx’s Critical Theory, was published in 1993. “The book is very widely read…if anything I could say in the last decade, it’s been read more. I’m sure that’s going to be an enduring work,” close colleague professor William Sewell said.

Beyond his scholarship on Marx, Postone also studied anti-Semitism. He edited Catastrophe and Meaning: The Holocaust and the Twentieth Century with Eric Santner, the Philip and Ida Romberg Distinguished Service Professor in Modern Germanic Studies.

A “Chicago-Lifer”

Although Postone considered himself “Left” or “radical” in the ’60s, he told the leftist Platypus Affiliated Society in 2008 that he did not think Marx was particularly relevant for social concerns at the time until he read the 1844 Manuscripts and English edition of Grundrisse translator Martin Nicolaus’s The Unknown Marx.

“Its hints at the richness of the Grundrisse blew me away,” Postone said to The Platypus Review.

A biochemistry major in the College and later a history master’s student in the 1960s, Postone encountered his early sources of inspirations on campus.

According to Boyer, Postone’s favorite class as an undergraduate was History of Western Civilizations, which was taught by Karl Weintraub (A.B. ’49, A.M. ’52, Ph.D. ’57). Upon receiving the Quantrell Award for Excellence in Undergraduate Teaching in 1999, over three decades after taking Weintraub's Core class, Postone would describe the legendary history professor to the Chicago Chronicle as his role model.

“What I remember most is Weintraub’s engagement with the material. He was able to convey his sense that the issues raised by the texts we discussed were really important, which is something I try to do as well,” Postone said.

Postone participated in the 1969 student sit-in at the University’s administration building protesting the firing of sociology professor Marlene Dixon, and led a study group named “Hegel and Marx” after the sit-in.

The study group considered it essential to understand the historical moment by reading social theory, including Georg Lukács, which Postone found to be “an impressive tour de force.”

Postone departed in the early ’70s for his doctoral program at Goethe-Universität in Frankfurt, Germany, where he would remain for over a decade. He studied with Iring Fetscher, who was a scholar of the “second generation” Frankfurt School.

After completing his dissertation in 1983, Postone returned to Chicago to work with the Center for Transcultural Studies before he became a William Rainey Harper Instructor for the Core at the College in 1987.

It was again on campus where Postone would become a world-renowned scholar of Marx and a central pillar of undergraduate and graduate teaching.

Leader of the Core

Postone’s leadership was essential to the construction and development of Self, Culture, and Society, one of the oldest social sciences Core classes in the College. His involvement stretched over three decades.

“The process is interactive. The more successful I am, the more autonomous the students become,” Postone told the Chicago Chronicle. “I enjoy teaching at the University a great deal. I draw considerable energy from it.”

Anthropology professor John Kelly, the current chair of the Core course, was recruited in the same group of Harper instructors as Postone in the late ’80s.

“I had just finished my Ph.D., and Moishe and I were part of one of the largest groups ever hired to start as Harper collegiate assistant professors…. Right from the start, there was this conversation about the past and future of social theory in the staff,” Kelly said.

Kelly remembered that at the time there was a division of labor among the staff, with scholars from different disciplines within the social sciences who were committed to different theorists. Postone was a great scholar of Marx as well as Freud.

“Between the group of us, we covered an enormous territory of the scope of the social sciences core. [Since then] it’s had a backbone, and that was Moishe’s leadership above all,” Kelly said.

In 1995, Postone became the chair of Self, Culture, and Society. He ran the weekly staff meetings during which he advised instructors on how to teach the class, worked with other chairs to hire Harper instructors, and over time built the course into an effective introduction to social theory that aims to teach students how to read and write independently.

According to Kelly, Postone’s mentorship was both charismatic and substantive, such that Harper fellows received almost the highest course reviews in college teaching.

Boyer noted, too, Postone’s important leadership in Self. “He was a very strong and forceful leader of that course, and he really was able to articulate a vision for over three quarters because it is a year-long course, in which each quarter built on the preceding quarter,” Boyer said.

“He had a good way of combining higher level, rigorous, intellectual exchange with a colloquial pleasantry, a kind of fun-loving outlook. Fun-loving is maybe a little too light, but he could be very jovial,” said Gary Herrigel, the Paul Klapper Professor in the College and in the Division of Social Sciences.

As chair of another social sciences Core sequence—Power, Identity, and Resistance—Herrigel worked closely with Postone as they developed the Core. Herrigel, who was also interested in capitalism and its modern developments, met Postone as soon as he joined the University.

Although they thought about capitalism very differently and had intellectual disagreements, Herrigel and Postone both believed strongly in the value of interdisciplinary general education, where students engage with fundamental texts of social theory. Herrigel said that the most important goal of the Sosc sequence for Postone was teaching students to be autonomous, to think about texts and make their own judgments independently.

According to Herrigel, Power, Identity, and Resistance was modeled after the existing, well-developed structures of Self and Classics.

“Moishe over time became an unbelievably caring, solidaristic mentor friend for me,” Herrigel said. “We were allies in defense of the Core, in defense of general education in opposition to the ever-present desire to make the sequences more discipline-focused.”

Herrigel and Postone both worked to hire Harper fellows to teach the Core, which involved selecting a few candidates each year from a pool of hundreds of applicants. “Moishe was always engaged, reading the files, learning about the candidates,” Herrigel said.

Jake Werner (Ph.D. ’15), collegiate assistant professor and a current instructor of Self, worked closely with Postone as a Ph.D. student. When Werner met with Postone to prepare for his oral exams, he sometimes found Postone working long hours grading papers. “It wasn’t his graduate students, it was his undergraduates’ papers. He really put himself into that,” Jake said.

When Kelly’s daughter studied at the University as an undergraduate, she took her first quarter of Self with Postone. “It just made common sense. She definitely changed her life to be Moishe’s student, so I still hear about that from my daughter,” Kelly said.

A Generous Mentor

Postone was also a popular and influential teacher among graduate students. He received the Faculty Award for Excellence in Graduate Teaching and Mentoring in 2009.

“Moishe was utterly committed to both writing and teaching, but would always sacrifice writing time to teaching if necessary…. He would teach his current work in his graduate courses, so his courses were always exciting and fresh. Students were completely energized by the chance to be there as he worked through his newest thoughts. He would also spend hours on dissertation chapters, helping students to hone their ideas,” wrote Postone’s colleague from the history department, professor Leora Auslander, in an e-mail.

“He was a teacher by calling. Some of our colleagues, they minimize the amount they teach, but others of them understand that they reach people [by] teaching in a way just as profound as they do in their writing,” Kelly said.

Werner remarked that Postone was extremely good at helping students understand dense, difficult texts, and always shed light on nuances in the texts that he and others often missed. Werner brought what Postone taught him into his own teaching in the Core: not only specific texts, but also the ability to understand and teach new texts.

Sewell told The Maroon that one of the graduate courses Postone taught was a series of three classes, starting with Marxist social theory, then the critical theory tradition, and finally what Postone called contemporary social transformations, which was about capitalism and society in the late 20th and 21st century. “Those courses were always oversubscribed…. It was really a formative experience for many students,” Sewell said.

Richard Del Rio, a graduate student from the history department, remembered first meeting Postone at a departmental barbecue—and took a liking to him because of “his no-nonsense, honest style.” Del Rio eventually took almost every course Postone offered.

“What I appreciated was the rigor of it. I appreciated the fact that Postone didn’t water anything down. He didn’t coddle his students,” he said.

A close colleague in the history department, Auslander said that Postone defended the so-called "Chicago tradition," which emphasizes knowledge for knowledge's sake, and argued against what he saw as the over-professionalization of graduate education.

“He thought that history was a vocation more than a profession and that students should take their time in graduate school to read deeply and widely, working gradually toward their own ideas,” Auslander said.

Del Rio said that Postone was always cordial. Even though Postone was not on Del Rio’s dissertation committee, he was supportive and encouraging.

“It was always nice when we ran into each other, we would talk briefly, shake hands, and he would say how important it was that I needed to graduate, and that he wanted to see me graduate soon, and now that he’s passed—it’s sad, because I am graduating, and I would have loved to share that with him,” Del Rio recounted.

“In my life I never saw him stop”

Postone contributed much to the strong scholarship on social theory at the University.

He was the co-director of the Chicago Center for Contemporary Theory (3CT), co-director of the Critical Historical Studies journal, and co-director of the Social Theory graduate student workshop.

Sewell co-directed the workshop with Postone beginning in 1991. What was especially exceptional about Postone, Sewell said, was his interdisciplinary approach.

According to Sewell, Postone not only supported students in the history department, but also sat on the student dissertation committees across various disciplines such as anthropology, sociology, German studies, and political science.

According to Kelly, Postone was also a phenomenal leader in workshops where voices from different disciplines and political stances were present. Kelly and Postone each chaired respective sections at a workshop on money and markets, engaging with economics faculty from Northwestern and the University of Chicago.

“He was brilliant, mixing the voices and posing questions that caused his speakers to have to disagree with each other in intellectually appropriate ways. It’s a real art form,” Kelly said.

Postone also emphasized the value of talking to scholars from around the world. He held conferences in Beijing, Taiwan, and Delhi over the years, and traveled to Japan and Brazil as well to engage with different voices. “He was really involved in getting these ideas out. He was focusing outward, not just inward,” said Werner, who has been working on the Chinese translation of Time, Labor, and Social Domination.

Colleagues remembered Postone as a deeply committed scholar, with whom one often had intellectual conversations. Boyer typified his relationship to Postone akin to how the social theorist Hannah Arendt defined true friendship: taking each other seriously enough to listen to, analyze, and even disagree with respective views.

“Moishe was that kind of a friend. He was not simply a person with whom you pass the day casually talking about the weather or talking about vacations, even children or grandchildren. He was always a man very much caught up in the swirl of ideas,” Boyer said.

Herrigel said that he and Postone disagreed often about capitalism and Marxism and had intellectual conflicts when they first met. Ultimately, however, Herrigel believed that across his career, he had learned the most from Moishe about what it meant to be an intellectual.

“Moishe could be maddening in all these different kinds of ways, but you could have an unbelievably sharp intellectual disagreement with Moishe and he would just buy you lunch the next day. He did not hold grudges. He tried to learn from exchanges and he respected the possibility of disagreement, and worked with that,” Herrigel said.

On several occasions, Kelly and Postone argued about whether to accept a Marxist totalization during workshops. They always disagreed on this critical question, but they would still sometimes ask the other to give lectures on Marx when one had to be absent.

“We respected each other’s judgment. We often had great conversations after each other’s lectures about some particular point in social theory that came up in one person’s review or another,” Kelly said. “This is going to be very, very much missed…leadership like his is just not easily replaceable. 3CT has a deep well of talented social theorists connected to it, but there are some people whose style and substance is just so memorable that it’s going to leave a big hole and it doesn’t get filled.”

Kelly remarked further that Postone possessed a profound courage. According to Kelly, Postone was always curious about and paid close attention to new arguments within social theory, but he was committed to his interpretation of Marx and dialectical analysis.

Even when there was widespread academic resistance against taking a Marxist total approach, Postone always made his arguments unhesitantly.

“In my life I never saw him stop. I saw him make his arguments with care, even saw him frame them [almost] apologetically, but never compromising the substance. And if he thought the analysis was wrong, he would say so, because it was his job, and it was his calling to make the argument he was making,” Kelly said.

Regardless of his specific approaches towards Marx’s social theory, however, the concern for the contemporary world and a lifelong dedication to education were central to Postone’s legacy.

“The stakes of his work were always clear; to understand and explicate the world in which we live in order to have the tools to work towards its transformation,” Auslander wrote. “We will very much miss his demanding presence.”

More even than as a rigorous teacher, students, and colleagues on campus remember Postone as genuine, charismatic, and kind.

“For someone with such a formidable intellect, Moishe was a genuinely sweet, caring, and playful person,” Levy recalled. “He had a spark of both intelligence and sympathetic humanity in his eyes.”

A memorial service for professor Moishe Postone will be held on Monday in Rockefeller Memorial Chapel at 4 p.m., followed by a reception in Ida Noyes Library.