Educators, activists, and artists alike gathered to celebrate the South Side’s rich culture in “Unfinished Business! The South Side and Chicago Art.” Featuring lectures, movie screenings, and art exhibitions, the weekend-long event was a collaborative effort by the department of art history at Northwestern University, the Museum of Contemporary Photography (MOCP) at Columbia College Chicago, and the Smart Museum at University of Chicago. The symposium worked in conjunction with exhibitions The Time Is Now! Art Worlds of Chicago’s South Side and The Many Hats of Ralph Arnold: Art, Identity & Politics, respectively held at the Smart Museum and the MOCP.

The symposium opened with a panel, moderated by DuSable Museum archivist Skyla Hearn, that explored the various ways through which the South Side has engaged with art over time. The diverse panel included acclaimed writer and journalist Natalie Moore, community educator Maséqua Myers, artist Faheem Majeed, and photographer Bob Black. Although each panelist had a unique take on how to impact their communities through art, they all echoed a same message: the importance of retaining the South Side’s authentic culture.

With eloquent certainty, Moore highlighted the importance of writing for people, rather than about them. She challenged the traditional notion of audience, warning of the fallacy of single stories. Aspiring artists in the crowd were invited to portray their truth or the truth of those around them. With natural stage presence, Myers spoke of the uplifting nature of art for the Black community. She reminded the crowd of the bleak history against which the rich culture of Bronzeville emerged, and of the beauty that had dared to blossom during segregation. While guiding the audience through a presentation of cultural landmarks in Chicago, Myers emphasized the importance of knowing one’s history and how liberating that knowledge can be. She closed with a picture of the South Side Community Arts Center, a landmark that serves as a reminder of the importance of preserving the cultural history of Chicago’s artistic revolutions.

The evening closed with two films about music and the Black experience, Ed Bland’s The Cry of Jazz (1959) and Harvey Cokliss’s Chicago Blues (1970). They explored the complex relationship between jazz, blues, and the Black experience. The Cry of Jazz made several controversial claims, most infamously that jazz is dead. It depicted jazz as a physical body, comparable to how America wanted to dehumanize Black people. The film went on to explain the metaphorical importance of jazz as a mediator of the hardships Blacks faced in the country, and how its form symbolized the ever-present paradox of freedom and restraint for Black Americans. Chicago Blues built upon an idea that suffering is a necessity in creating a genre like blues. Images of men with their guitars, making up lines on the spot to an iconic blues chord progression filled the screen. Diving into the institutional discrimination of the Black population in Chicago, scenes of playing children contrasted the bleak narration of their everyday reality. Eerily, many of the issues Cokliss captured on screen 40 some years ago still ring true today.

One of the symposium’s most charismatic and spirited presenters was radio-host Ayana Contreras, who is writing a book called Energy Never Dies about the cultural contributions that Black Chicago has made within society after the civil rights era. She credited Curtis Mayfield as one of the pioneers of this movement starting in the ’70s, and passionately worked her way up to the present day. She herself has worked with Chicago musicians Chance the Rapper and Noname as young adults. Her conviction made it easy to see the natural talent that bubbles in all parts of Black Chicago, and she plans to harness this potential through spreading the values of community spirit and confidence.

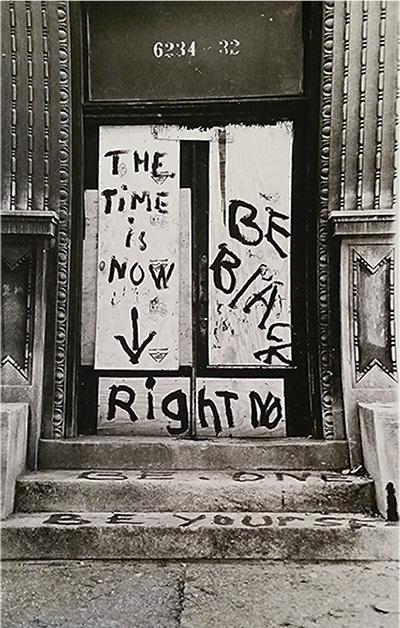

Monica Trinidad provided the standout visual arts speech of the day. She is a self-proclaimed “radical artist” pushing movements for justice all across Chicago. Drawing lessons from the history of injustice in Chicago, she hearkened back to the spirit of the Memorial Day Massacre of 1937, in which unarmed protestors marched on Sam’s Place. The police subsequently opened fire, killing 10 people. She conveyed that prisons and policing today “thrive on forgetting” events such as this one to maintain the status quo. She stressed the importance of “visual curriculums” told by visual artists to convey powerful message, and that visual art is one of the most effective forms of communication in this way. Echoing other presenters who criticized the move, she trashed Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s plan to create a $50 million police academy while simultaneously shuttering several South Side schools.

75-year-old Abdul Alkalimat delivered the most convincing presentation of the symposium and had me walking away with his booming voice still echoing in my head. A natural-born speaker, Alkalimat touched on issues such as the responsibilities of Black artists to stand up against oppression and to hearken back to their roots, which can be interpreted as a pointed dig toward Kanye West and his cozying up to President Donald Trump. He passionately remarked on how the baby boomers nostalgically remember the ’60s, quipping that “when they talk about the ’60s, they’re not talking about our [Black] ’60s.” The pop culture image of the ’60s omits the extreme hardships of Blacks making their way through the midst of the civil rights era. He stressed social consciousness, not only for Blacks, but for all citizens. He also remarked that “we [people of color] can afford the truth, while white people cannot,” explaining that white people’s ancestry is tarnished and stained by talks of slavery and other injustices, while people of color are free to discuss past injustices without feeling as if it reflects badly upon themselves. His talk painted a picture of the troubled past, present, and future of racial struggle, and helped the audience to see how these issues manifest themselves in society today, since it is a lot harder to analyze the effects of racism and injustice in the present than it was in the ’60s with the added influence of hindsight.

While the day was a celebration of the joy and beauty created from hardship, it was also a bleak reminder of how much more progress still needs to be made. As Myers so beautifully stated, “Where do you start, and where do you begin? Well, you start from where you are right now.”