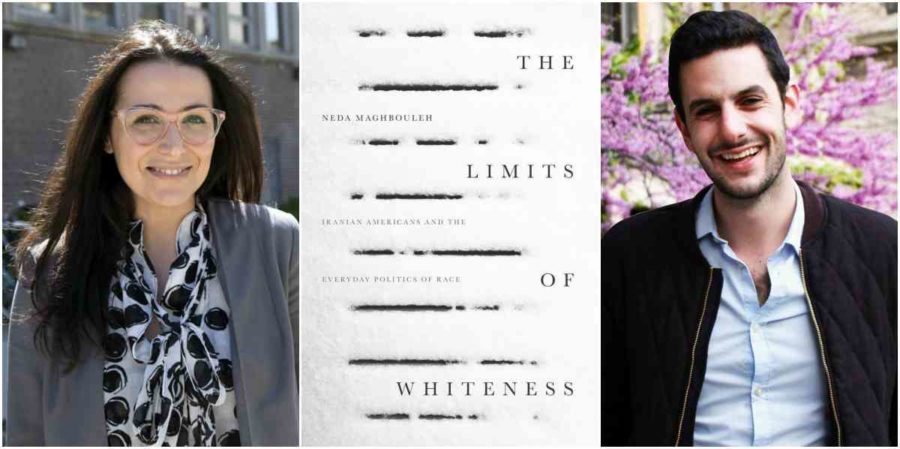

On February 6, Iranian-American sociologist Neda Maghbouleh debuted her new book, The Limits of Whiteness, at the Seminary Co-Op Bookstore, and discussed several of its premises with Alex Shams, a Ph.D. candidate in anthropology.

An assistant professor of sociology at the University of Toronto, Maghbouleh read the first few pages of her book, after which she recounted some relevant anecdotes about her own experiences as a second-generation Iranian-American, as well as stories she heard while doing research. Shams, also Iranian American and editor-in-chief of Ajam Media Collective, then read an excerpt from an essay he had written about the Aryan myth within Iranian communities. The event ended with a table covered in Middle Eastern cuisine.

The Limits of Whiteness opens with the case study of Roya, an Iranian-American student exasperated by having to check “white” on standardized test surveys and other documents whilst being grouped into non-white social circles at her high school. Roya exemplifies the dichotomy between Iranian Americans’ perennial identification (and self-identification) as non-white and their legal categorization as white. The juxtaposition leads to everyday contradictions that Maghbouleh terms “racial loopholes.” Her book uses this concept to explore the elasticity and boundaries of whiteness as well as the significance of Iranian Americans’ placement at the fringes thereof.

Maghbouleh’s book has a tone of urgency in the face of the recent executive order barring Iranians and other groups from immigrating to the United States. The possibility of Iranian Americans being legally excluded from the “white” racial category poses a potential threat to their position. Maghbouleh coins the term “racial hinge” to refer to the phenomenon of Iranian Americans receiving different racial labels depending on the context.

The third chapter of Maghbouleh’s book outlines another racial discrepancy that Iranian Americans face. Specifically, she examines the contrast that second-generation youths experience between their domestic racialization as white by parents and their determination as colored by schoolmates. The former phenomenon is a manifestation of the Aryan myth, whose origins Shams digs into in his essay “A 'Persian' Iran?: Challenging the Aryan Myth and Persian Ethnocentrism.” He describes Aryanism as an ideology positing the “migration of an imagined Aryan nation out of India, through Persia, and into Europe” as a basis for Iranian racial supremacy—one that situates them as the original whites. Maghbouleh’s interviews reveal the way this belief leaves Iranian-American youths feeling alienated by both their first-generation parents, who were raised with Aryan conceptions, and their Caucasian-American classmates.

Another topic of the evening’s discussion was Camp Ayandeh (Farsi for “future”), which Maghbouleh writes of in the sixth chapter of her book. Founded and run by Iranian Americans, the summer camp fosters a sense of family between Iranian American youths, legitimizing their racialized experiences and celebrating a sense of kinship with other racially marginalized groups, such as Arab Americans. Running since 2006, the two-week program involves a myriad of activities, including close readings of media depictions of Iranians, as well as talks by guest speakers. Among their most notable speakers was Moustafa Bayoumi, who wrote How Does It Feel to Be a Problem?: Being Young and Arab in America, a book detailing the experiences of Arab Americans facing racial, ethnic, and religious discrimination post-9/11.

With research based on qualitative data collection, Maghbouleh’s book is brimming with an abundance of unique contemporary case studies, which she couples with legal and historical evidence in deep, thoughtful analysis. Her work is less an attempt to reframe certain concepts of race and assimilation and more a contribution to a speculative conversation about the functioning of whiteness in modern-day America, and the way this affects those groups at its very borders.