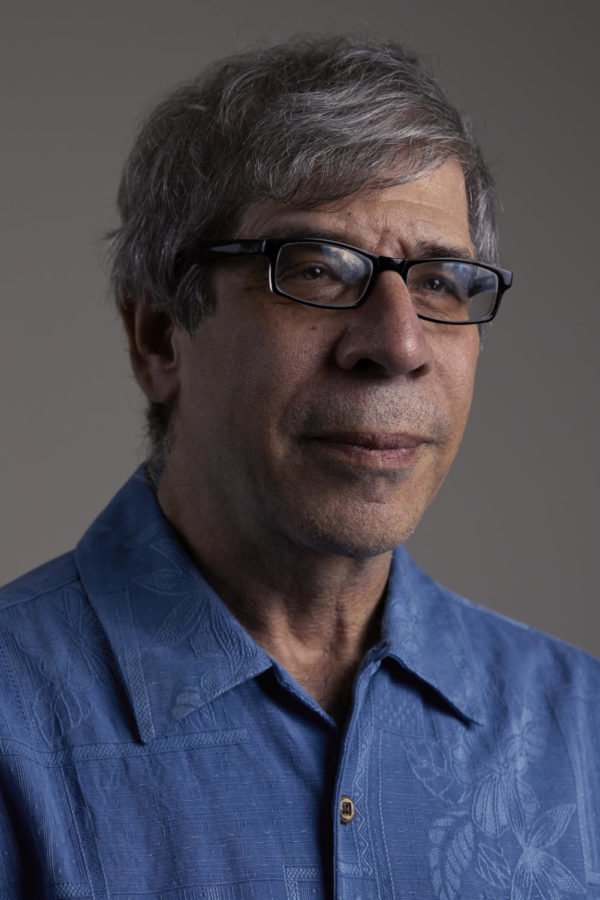

Jerry Coyne officially retired in 2015, but continues to come into his lab in Zoology 309 every day, publishing even more prolifically than he did during his scientific career.

Now, he writes for an audience of more than 50,000 e-mail subscribers to his blog, Why Evolution is True, discussing issues spanning science and medical ethics, atheism and determinism, philosophy, and free speech. Coyne is also one of The Maroon’s most frequent online commenters, often challenging the paper’s coverage.

Coyne originally gained attention outside the scientific community for his public critique of religion, and is often cited alongside celebrity “New Atheists” such as Richard Dawkins and Sam Harris. He has held numerous public debates with Christian creationists, and authored Faith vs. Fact: Why Science and Religion are Incompatible, along with New York Times bestseller Why Evolution is True.

When I met Coyne on Tuesday, February 6, he’d been blogging since the early hours of the morning. At 7 a.m. he posted a piece featuring a cartoon on free will and a video of cryptic mantis; by 8 a.m. a series of reader-submitted wildlife photos; at 9 a.m. a news update on hate speech allegations at Stanford; and at 10:30 a.m. a denunciation of a new grant by the Templeton Foundation, a religious research organization.

I sat down with Coyne in his lab to discuss his work, his time at the University, and a few of his most contentious opinions.

ON ABORTION AND POST-BIRTH EUTHANASIA

Coyne has advocated for access to late-term abortion services, citing the lack of fetal sentience—along with philosophical justifications—for terminating pregnancy. “I’m in favor of unrestricted abortion,” he told me.

“A woman should be permitted to abort a child up to when it's born, although she should also be aware that, at least in the U.S., there are lots of people waiting to adopt infants.[…] And, along with philosopher Peter Singer, I favor parents being allowed to end the suffering of a newborn if it has a medical condition so severe that it would suffer for a while and then die, or remain in a vegetative state. I see no point in a newborn having to undergo prolonged suffering if it is certain to die, and one can use painless ways to end the suffering.”

Despite his radically pro-abortion stance, Coyne insists that the abortion debate is more complex than the left often acknowledges, especially when dealing with claims of “rights.” While pro-choice advocates often try to reduce the issue to a woman’s “right to choose,” Coyne points out that “rights” arguments are a slippery slope, since one could equally postulate that a fetus has a right to life.

To counter “fetal rights” claims, Coyne looks to arguments such as philosopher Judith Jarvis Thompson’s Defense of Abortion to vindicate a woman’s right to her own body, even granting that the fetus has a right to life.

“In order to take a stand on abortion one way or another, you can’t just say ‘a woman has a right to an abortion.’ Because the other side can say, ‘there’s a fetus in there that past a certain time could live on its own,’” Coyne said. “Too often, abortion proponents just say, ‘a woman has a right to her own body.’ It’s not as simple as that. The assertion of rights really trumps any kind of counterargument. When you hear someone saying they have the right to this or that, you have to be careful.”

Last summer, Coyne’s blog post on post-birth euthanasia, Should one be allowed to euthanize severely deformed or doomed newborns?, was picked up by Breitbart and the National Review, who framed the piece as advocating “infanticide.”

“Now I am become Professor Death, the destroyer of infants,” Coyne sarcastically titled his blog post on the controversy (he was paraphrasing theoretical physicist and atomic bomb developer J. Robert Oppenheimer's statement, “Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds”).

Despite his flippant reaction, Coyne said that the broadside wasn't easy to handle.

“When I wrote the piece on favoring euthanasia for terminally ill newborns, man, I really got hit. Because, it’s like you’re calling for death camps and Hitler,” he said. “If you have a public presence and you’re not afraid of saying what you think, you’re going to get in fights. You have to have a very tough hide. And I’ve had a lot of pain, that I keep to myself, from doing this kind of stuff. But it’s immensely liberating to be able to have a platform to say what you think about things. If I say on my website that I don’t believe in free will, 53,000 people are going to read that.”

ON FREE SPEECH AND THE LEFT

Coyne says his experience as a proponent of contentious, often progressive views motivates his defense of free speech, and he is therefore frustrated at what he sees as a failure by contemporary liberals to uphold the traditional liberal value of free expression. Coyne insisted that his leftist “credentials” are unimpeachable, and that his denunciation of left-wing activity is a critique of liberal political means, not policy.

“When I was in college, I was arrested for delivering a letter to the South African embassy against Apartheid. I went to all the big demonstrations against the Vietnam war,” he said. “So my credentials are pretty impeccable. But I cannot stand my side of the political fence engaged in trying to make people shut up. It’s embarrassing!”

Coyne sees himself as a traditional liberal, and says he comes into conflict with contemporary leftists as often as he does with conservatives.

“The Republicans are useless. I can’t abide them; I hate their machinations, I hate their platform. But there’s nothing I can do about that. Whereas, being someone on the left, I can at least call out people on my side of the fence for their behavior—both the students and the faculty. And the left bothers me more than the right wing, because the right wing is beyond the pale, whereas on the left, here are people who are supposed to share my political outlook, and yet they’re engaged in a traditionally non–left-wing activity: trying to shut people up.”

Coyne was also concerned by the recent controversy at the Law School, when the conservative Edmund Burke Society, a debate group, issued an incendiary whip sheet many deemed racist. He was “disturbed” that the University did not take action to protect the Society’s free speech after they indefinitely postponed the debate, citing fear of student retaliation or “disturbance” at the event. (The chairman of the Society later followed up and apologized for the incident.)

Coyne took the same speech-protective view of Steve Bannon’s invitation to campus. “I can’t think of a single person I would urge the University to disinvite. Not a single person—not a white racist, not an anti-immigration person. Free speech has to defend the most odious people.”

ON “IDENTITY POLITICS”

Coyne is skeptical of so-called “identity politics” in social justice campaigns, saying legitimate grievances are often overshadowed by emphasis on categories of identity or attempts to shut down free discourse.

“Back in the ’60s, when black people were trying to get civil rights, or when the Women’s Movement started—that’s identity politics, and I have no objection to that. It was an identifiable marginalized or oppressed group fighting for their rights. So what am I objecting to now—I guess it’s not the politics I’m objecting to, so I probably shouldn’t use the term ‘identity politics,’ I should use the term ‘identity tactics.’ Because it’s no longer the way it was in the ’60s. It’s an attempt to set up a hierarchy of oppression and locate yourself on that hierarchy in a position where you are pretty high up. That gives you a certain cachet. In the ’60s, victimhood was not something to be proud of, but something to be fought against. Now, it’s something to be proud of, I think, because it enables you to get attention and to be able to say others in the hierarchy can’t speak, that they don’t have opinions worthy of considering.”

“I believe in social justice, I believe insofar as marginalized groups are treated badly that should be rectified—but not when people are doing it through a self-promoting victimhood narrative,” he said.

ON UNIVERSITY CULTURE

Coyne praised the UChicago faculty autonomy and commitment to free expression and said that the University has not changed substantially over his 30-year tenure. However, he’s concerned about identity politics and the rise of “consumerism” among students.

“By and large, it’s a free thinking culture. The University is run largely by the faculty, and it encourages discussion. The change I have seen is in the student attitudes, the rise of identity politics over the last five years, and the rise of consumerist culture for education, which might go hand in hand with the fact that good jobs are hard to get, coming out of college now, so the students want to be assured that they get trained rather than educated,” he said.

Coyne is also wary of the proposed new undergraduate business economics major. Noting that he doesn’t know the details of what the program would entail, he stressed the general value of liberal arts education over narrow careerism.

“The U of C is a liberal arts school, and I think the students should be given a liberal arts education. What I'm not sure about is whether the business major would preclude that. If not, then I’m not strongly opposed to it, though I don’t see why business school can’t be left until after college, as it usually is,” he said.

“I am opposed to the general trend of creating majors designed to funnel students into a given career path, for that way they miss out on some of the wonderful things they could learn (philosophy, fine arts, literature, and so on) that they’ll never get a chance to study again.”

ON GRADE INFLATION

Coyne laments that over the years, the higher-ups gradually stopped letting him give so many Cs.

“There’s no doubt there’s been grade inflation over the time I’ve been here. The first few years I was here, something like 10 percent of all the Cs in the division were given by me. [Then,] somebody let it be known to me that I really shouldn’t give so many Cs. As the years went by, the grades that I gave to my students, which were given in consultation with my TAs and the division, went higher and higher and higher and higher.”

“If everybody gets an A, what’s the point? What’s the point of grading at all; why don’t you just do what Reed College does, where you have a written evaluation?”

ON DETERMINISM

Coyne says that he was instantly converted to determinism, one of his top blog topics, when he read biochemist Anthony Cashmore’s paper on determinism and the criminal justice system. Determinism, the theory that all events and actions are predetermined, is generally taken to preclude the possibility of free will (Coyne defends this view, and has hotly debated “compatibilist” determinists, who believe free will and determinism are compatible ideas).

“I got to the sentence that said, ‘you have no more free will than a bowl of sugar,’ and I realized instantly that the guy was right,” he said. “Our brains are made of matter, and our behaviors are products of our brains, and we’re made of matter. Therefore, every atom in our body has to obey the laws of physics, which are by and large deterministic. So there’s no way that we can control, in any dualistic way, what comes out of our brain. Everything that comes out of our brain is deterministic and predictable at the moment you do it.”

Coyne acknowledged that while he believes free will is indisputably an illusion, he still finds it challenging to overcome the instinctive feeling of agency.

“Now, we feel that we could have [done otherwise than what we did]. All of us, including me. We have such an overwhelming feeling of agency. God knows how we got it; probably through evolution, but we don’t know. It’s impossible to feel that you’re a marionette, even though you intellectually accept it,” he said. “It’s like death—we know we’re going to die, but people manage to avoid thinking about it. So, everyone has the feeling of agency. And they feel like they’re making decisions, and they run their life on this basis. It’s all an illusion, of course, just like consciousness itself is probably an illusion. The feeling that there’s an I, that there’s a Jerry Coyne up here, steering the rest of me to do things—that’s an illusion. There isn’t such a thing. It’s just the entity that’s constructed by various reactions in our brains.”

“I don’t think people bear any moral responsibility for what they do, because the term “moral responsibility” implies that you could have done something differently from what you did, and you acted immorally. But no criminal—or anybody—can choose to act differently from what they did.”

Coyne said that a deterministic worldview has direct consequences for politics, too.

“A lot of politics—particularly Republican politics—is based on the supposition that people are responsible for their own lives. So, for example, people who are on welfare, or homeless people, are treated as if they could have done otherwise. They could have gotten a job, they could have gotten married and had a father for their kids. But they couldn’t, because they’re victims of circumstance.”

“Determinism makes you more empathic. Instead of blaming people for their actions, and saying, ‘there’s a welfare queen buying tuna on food stamps,’ which is what Republicans say, if you realize that people can’t do other than what they did, you acquire a degree of empathy. It’s against what’s called the Just World syndrome, which a lot of authoritarians and right-wingers have—that the world is set up justly and people fall where they fall because of their own choosing. If you’re a determinist, you know that’s not possible; people fall where they fall because of their genes and their environment, and they have no choice in the matter. So I don’t think determinism flattens empathy at all; if anything, it should sharpen it, because it means people are not morally responsible for their own situations.”

At a talk at the 2015 Imagine No Religion conference, Coyne elaborated his argument for the validity and merits of a deterministic worldview.

ON OBJECTIVE MORALITY

While he recognizes the merits of deterministic empathy, Coyne maintains that a scientific worldview precludes any standard of objective morality.

“All morality is based on preference; there isn’t any objective morality. We’ve hit on, in general, a kind of moral landscape in which we regard the overall flourishing of society as a good. But some people don’t agree.”

Coyne’s rejection of objective morality sets him apart from Sam Harris and other proponents of determinism, who argue that it’s possible to define an absolute scientific basis for moral judgments.

“‘What is the right thing to do?’ ‘What kind of morality, what kind of laws should society have?’ Those are meaningful questions, but science can’t tell us the answer to those. Sam Harris thinks there are objective answers to these ‘scientific’ questions. He thinks ‘That which makes well-being increase’ is scientifically the right thing to do. But that’s still a preference—that’s placing wellbeing as your locus of preference.”

ON HIS WORK IN EVOLUTION

It was only towards the end of our talk that Coyne and I got around to discussing the bulk of his academic career: his research on biological evolution and speciation.

Coyne conducted his experiments on Drosophila (fruit flies) for all but his very first academic paper, which dealt with population growth of the polyps of a jellyfish. He describes his work as directly exploring the original problem raised by Darwin: the origin of species.

Coyne’s lab team examined genes causing reproductive isolation, the dynamics of chromosome evolution, and various aspects of ecological genetics. Although his office is no longer an active lab, he has one last forthcoming paper, which will deal with fruit fly hybrids.

I asked Coyne what practical applications his work has. “None,” he said.

“A lot of people ask this—even my parents asked me. And the answer is, I do the kind of science which is purely the satisfaction of curiosity. And that’s one reason I came here—more than where I was before, the University of Chicago is one of the freest schools in the U.S., in terms of giving you complete freedom to work on what you want. Nobody was there to tell me what to do. The teaching load is not so onerous that you can’t spend most of your time doing research, so I’m in the enviable position of being able to satisfy pure, untrammeled scientific curiosity, and get paid for it. Now, I publish and I write stuff; that’s my way of paying back the people who support me, the federal taxpayers. But in terms of the practical use of evolutionary genetics? Not much.”

“I look at evolutionary biology as more like the fine arts of science, in that it’s aesthetically quite satisfying, but it also happens to be true, which is an extra bonus. So, I contribute to the wealth of knowledge about the universe. You can say the same about cosmology. I mean, what has knowledge of the Big Bang ever done for anybody on this planet? Nothing! But isn’t it satisfying to know that 14.6 billion years ago, there was a gigantic inflation of the Universe, and before that, there was no time? It’s stupefying. So what I do is not really expand people’s pocketbooks or make them healthier; I expand their minds, or I try to.”

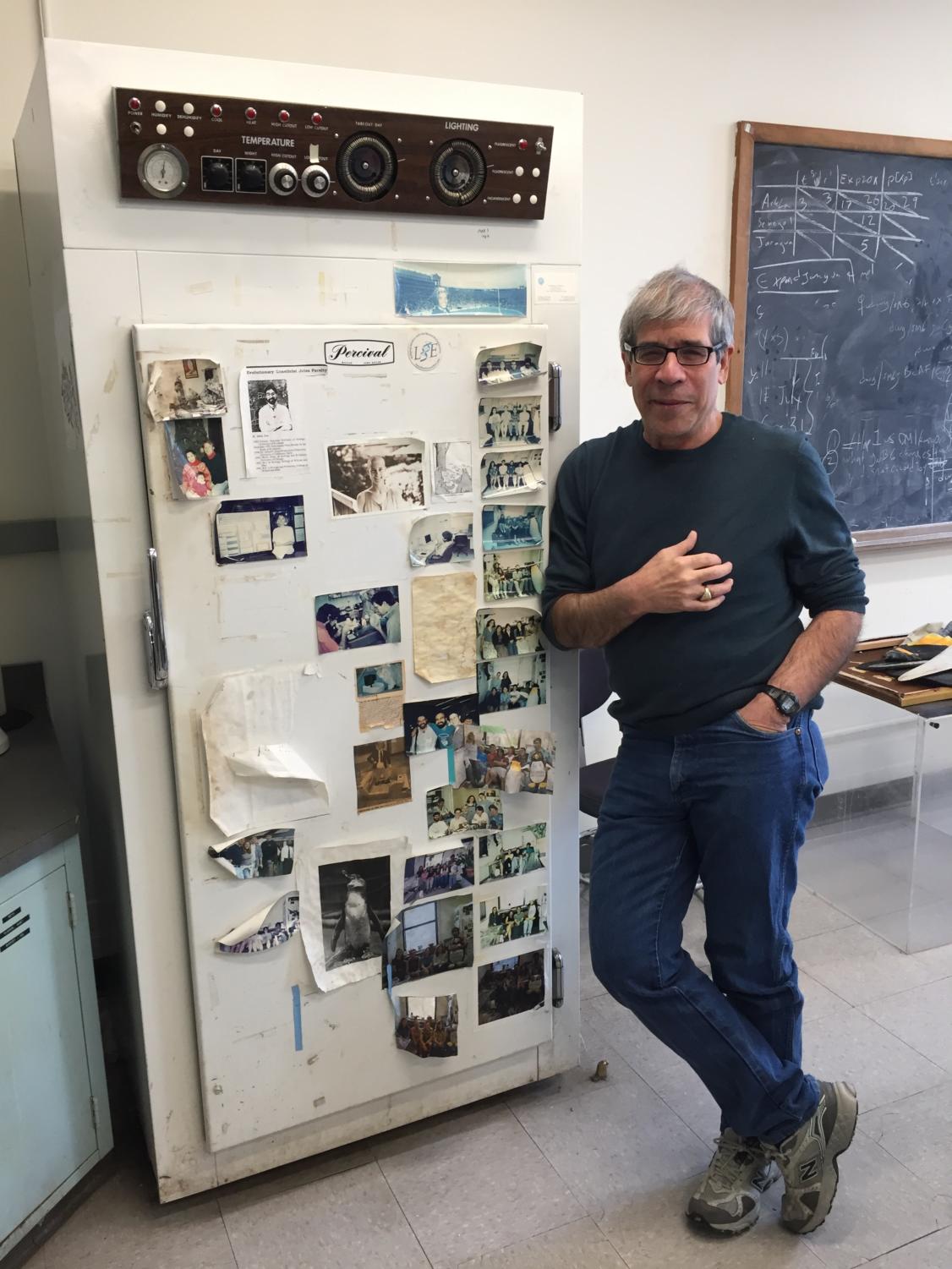

THE LAB

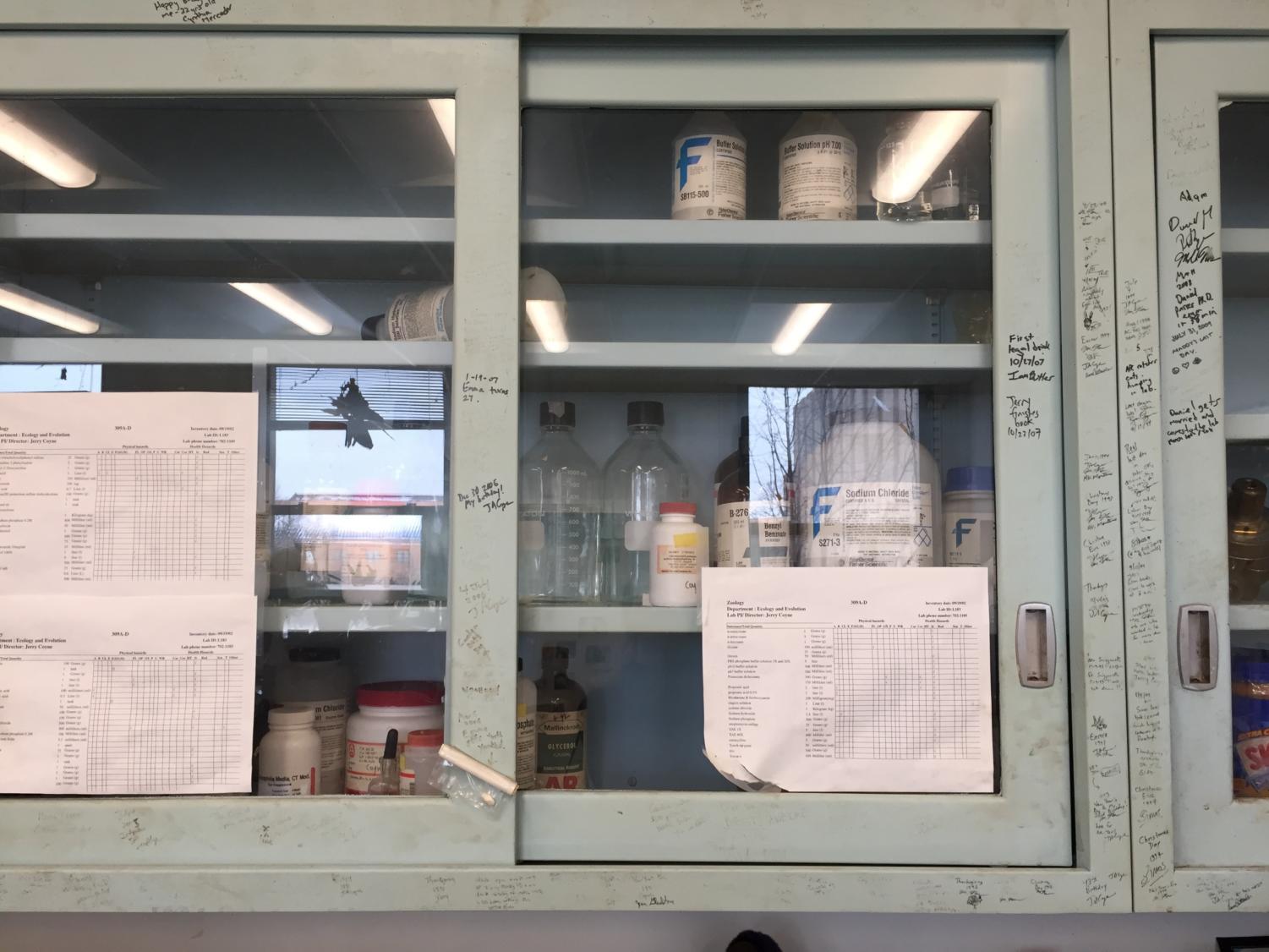

Coyne, who often worked seven days a week and says he spent more time at the lab than at his home, encouraged postdocs and researchers who worked in his lab to sign a lab cabinet every time they came to work on a holiday or special occasion.

A few inscriptions read:

- “Christmas Day, 1994”

- “First legal drink 10/27/07 -Ian Butler”

- “Daniel gets married and comes to the lab, March 10th”

- “Last day in the lab! Aloha. -Ryan 8/19/94″* and“*Real last day in lab. Ok, this time it’s fo’ real eh? -Ryan [undated]”

- “Thanksgiving 1992”

- “AFC catches cats humping in lab.”

Detlef Pelz / Feb 18, 2023 at 11:45 pm

Did Professor Coyne ever marry? There is scant information about his personal life on the internet. However, he has a right to keep his personal life private and I respect that. Besides, the fact that he’s an animal lover, especially of domestic cats (as I am – it’s what drew me to him many years ago), and his abiding atheism and determinism, tells me all I really need to know about this esteemed man. But, as I am Prof. Coyne’s junior by 20 days (19 January 1950), perhaps he will forgive my noseyness.